Lessons of San Pedro Ranch

Lessons of San Pedro Ranch

By Henry Chappell

Photography By John Dyer

LR_SanPedro-01

SPANISH LAND GRANT. Centuries old, the historic ranch was a critical landmark for conquistadors and other explorers thanks to its precious waters.

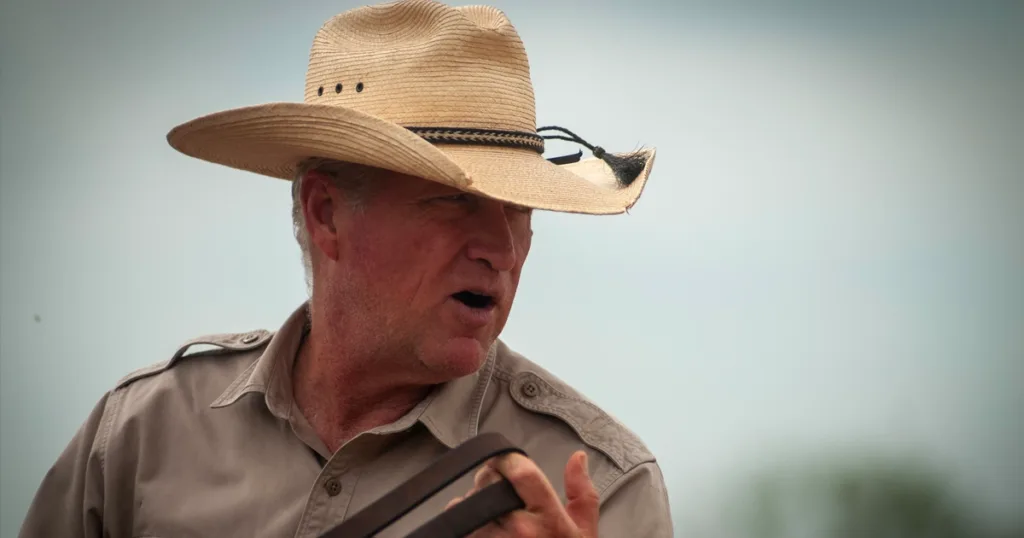

People often ask Joseph Fitzsimons, 65, how growing up on the San Pedro Ranch made him such a staunch advocate for public lands. The third-generation Texas rancher served a six-year term on the board of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission, including as its chair; has been a director of both the Texas Wildlife Association and the Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association; and is currently championing Proposition 14, a ballot initiative that would create a billion-dollar fund to acquire and develop new parks in the Lone Star State.

Historic San Pedro Ranch

The answer to Fitzsimons’s private-public duality can be traced back to the historic San Pedro, where the values that the man, his wife, and generations of their families hold dear with regard to the responsibilities of private landownership have long been nurtured.

Fitzsimons grew up in San Antonio. Countless weekends and summers were spent 150 miles southwest of the Alamo City on his family’s San Pedro Ranch. The days and nights he and his sister, Pamela Fitzsimons Howard, spent on the 23,000-acre ranch created a profound appreciation for the rugged ranch and its stewardship, an appreciation he has promoted as a private landowner and a public servant.

Acquired for only the third time in 1932 by Hugh Fitzsimons Sr., the San Pedro was like much of South Texas: It was once part of a Spanish land grant. The historic ranch is the site of an iconic spring that quenched native tribesmen, conquistadors, and early settlers. The only live water between the Rio Grande and the Nueces Rivers, the San Pedro spring flows even during the worst droughts. Through this wellspring, Fitzsimons’s father, Hugh Fitzsimons Jr., instilled in his children the importance of the cycle of water on their ranch, its effect on plant communities, and the combined effects on wildlife and cattle.

Resource and Habitat Business

“My father recognized that over the long term, we were in the resource-and-habitat business. We have an integrated approach to livestock and wildlife management. Our philosophy is that if we work to maximize native habitat with an ecological approach, then the livestock and wildlife will benefit,” he says.

Fitzsimons and his sister were taught that careful grazing management and constant attention to the health of native grasses and forbs on the San Pedro Ranch ensured that rainfall percolated into the water table. “I see that spring as symbolic. I don’t want it going dry on my watch,” Fitzsimons tells me on a phone call from the San Pedro.

SAN PEDRO SPRING. “I see that spring as symbolic. I don’t want it going dry on my watch.”

Learning About Land

At 17, he took a job working for Texas Parks and Wildlife on a desert bighorn sheep research project at the rugged, remote 103,000-acre Black Gap Wildlife Management Area in the Big Bend of Far West Texas. “I spent a lot of my time chasing mountain lions,” he says.

After studying at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon, Fitzsimons worked on ranches in the American West and in South America. Hard times almost cost the family their beloved ranch. “It was pretty clear to me that ranching alone wasn’t going to support the whole family, so I went to law school in 1982.” Three years later, Fitzsimons graduated from the School of Law at the University of Texas at Austin. Not long afterward, he married Blair Calvert, whose family owns the Calvert Brothers Ranch in Frio County.

The newlyweds moved from San Antonio to the San Pedro Ranch. While Joseph established his law practice, Blair homeschooled their three children and ran the day-to-day operations of the ranch. They lived on the ranch until their children grew up, at which point the family returned to San Antonio. Brand-new chapters awaited each of them.

Return to San Antonio

In 2001, Texas Governor Rick Perry appointed Fitzsimons to the board of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission. In 2006, Fitzsimons became its chair. He also co-founded Uhl Fitzsimons, the San Antonio-based law firm that represents land and mineral owners and specializes in energy, water, and conservation law.

Simultaneously, Blair founded the Texas Agricultural Land Trust (TALT). The organization proudly proclaims that it was “founded by landowners for landowners.” TALT endeavors to conserve the heritage of agricultural lands, wildlife habitats, and natural resources throughout Texas. In 2009, the Fitzsimons and Howard families dedicated an easement on the San Pedro Ranch through TALT. Blair served as founding CEO of TALT for more than a decade. Blair, her two sisters, and a cousin placed a conservation easement on their beloved Calvert Brothers Ranch in 2020.

During the pandemic, Joseph and Blair sought refuge on the San Pedro, and they remain there to this day. Wildlife and a registered Beefmaster herd generate most of the ranch income. Whitetailed deer, turkey, and both bobwhite and blue quail abound.

LANDED. Joseph served as chairman of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission, and Blair founded the Texas Agricultural Land Trust.

Fitzsimons’s current project? To lever the broad knowledge base acquired as a private landowner to benefit a much wider audience.

“Texas is clearly an urban state now,” he says. “There are more state senators and representatives from Houston than there are from the rest of the state west of I-35. All our private lands work with the Texas Wildlife Association, and the Society for Range Management doesn’t mean a thing to urban residents who’ve never experienced the outdoors.”

“Sick to the Point of Dying”

That’s a tall order, given Texas’s checkered history of funding state parks. Founded in 1923, the Texas State Parks Board was merged with the Game and Fish Commission four decades later. Governor John Connally authorized the merger in a last-ditch attempt to salvage the faltering agency.

“Our present state parks system is sick to the point of dying,” Connally said at the time. “Our parks are many, scattered, and without tourist-attracting features needed for effective use …. We must decide what we want in the way of parks and what it will cost, then provide this service to our people or not attempt to engage in the activity at all.”

Time and again, Fitzsimons has rallied to Big John’s challenge. “My bride always says that land is infrastructure, whether it’s watersheds, wildlife, or agricultural production. Our development and our population have gotten well ahead of our ability to provide public land, outdoor access, and education. We’ve got a hell of a lot of catching up to do,” he insists.

Centennial Parks Conservation Fund

On November 7, Texans will finally have an opportunity to right decades of underfunding their state park system. The Centennial Parks Conservation Fund will provide $1 billion for the acquisition of new parkland. If passed, Proposition 14 will draw from the Texas Rainy Day Fund, which is replenished via taxes on oil and gas revenue.

Says Fitzsimons, “What I do just isn’t relevant if most of the people in Texas don’t know what a watershed is or if they haven’t experienced the outdoors. Given the convergence of urbanization, the loss of rural lands, and the concentration of voting power in the cities, are we going to lose our natural uniqueness; the things that have made people want to come to Texas? We’ve got a lot of work to do.”

NUMEROUS HONORS. Stewardship of the San Pedro is an ingrained tradition. In 2005, it won the Outstanding Rangeland Stewardship Award from the Texas Society for Range Management. A Lone Star Land Steward Award came in 2016. In 2020, the Sand County Foundation bestowed the Leopold Conservation Award.