Lessons of San Pedro Ranch

Lessons of San Pedro Ranch

By Henry Chappell

Photography By John Dyer

LR_SanPedro-03

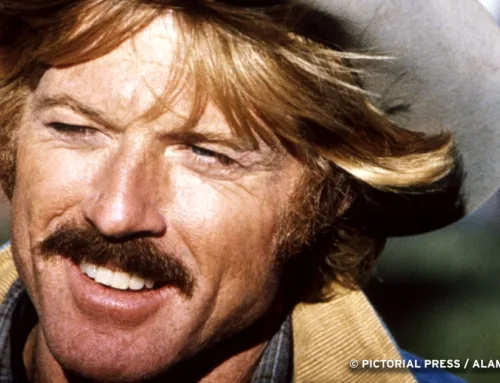

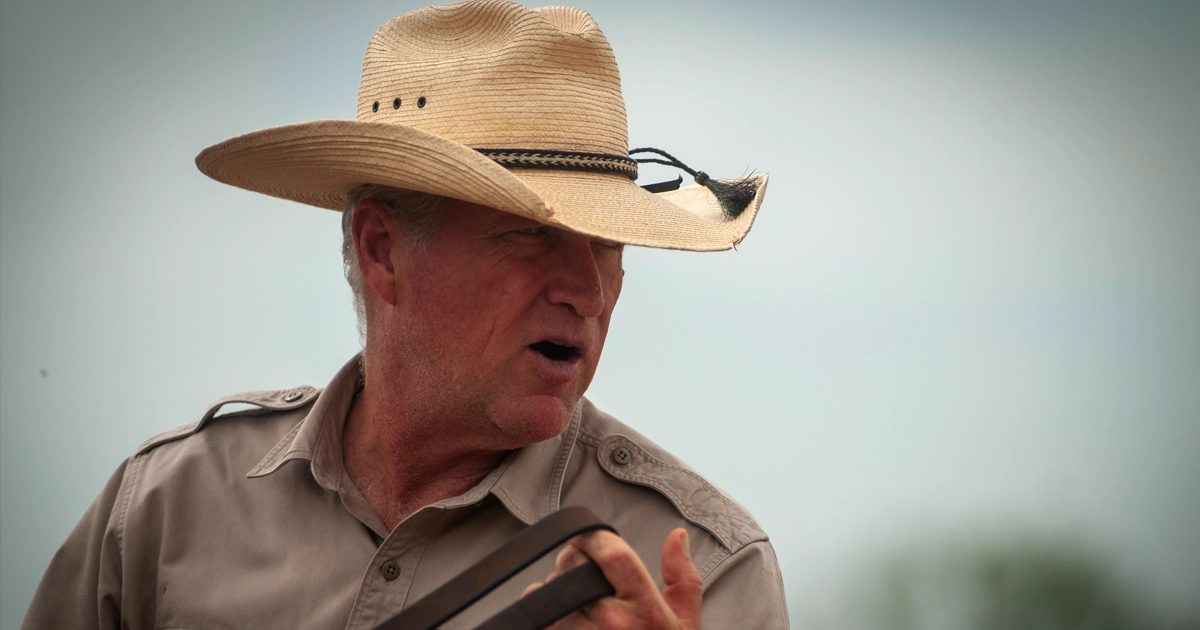

PRIVATE-LAND STEWARD, PUBLIC-LAND CHAMPION. Joseph Fitzsimons relies on lessons learned on the historic San Pedro Ranch to enrich the lives of millions of his fellow Texans through public parks.

Over the course of his 65 years, San Antonio native Joseph Fitzsimons has witnessed a dramatic evolution.

“Texas is clearly an urban state now,” the third-generation rancher is comfortable admitting. “There are more state senators and representatives in the legislature from Houston alone than there are from the rest of the state west of I-35. All our private-lands work with the Texas Wildlife Association and the Society for Range Management doesn’t mean a thing to urban residents who have never experienced the outdoors.”

Fitzsimons’s staunch advocacy for public lands is a product of his many experiences on both private and public lands. Growing up in San Antonio, he and his sister, Pamela, made countless trips to their family’s San Pedro Ranch in South Texas. Soon after his 17th birthday, he interned with the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department at the Black Gap Wildlife Management Area. His primary focus was a desert bighorn sheep research project.

“I spent a lot of my time chasing mountain lions,” Fitzsimons says.

After attending Lewis & Clark College in Oregon, he worked on ranches in the American West and South America. The 1980s were not kind to the Fitzsimonses, however. They nearly lost their beloved San Pedro Ranch.

“It became pretty clear to me that ranching alone wasn’t going to support the whole family, so I went to law school in 1982,” he says. Three years later, he graduated with a JD from the University of Texas at Austin. By then, he had met and married Blair Calvert, whose family owns the Calvert Brothers Ranch in Frio County. The couple moved from San Antonio to the San Pedro, and Fitzsimons opened his own law practice in Carrizo Springs. While Fitzsimons practiced law, his bride oversaw the day-to-day operation of the ranch and homeschooled their three children.

RANCH CONNECTION. Fitzsimons (left) met and married Blair Calvert (right) in 1984 while in law school.

Historic San Pedro Ranch

Purchased in 1932 by Fitzsimons’s grandfather, the San Pedro Ranch takes its name from a lush spring long prized by Native Americans, Spanish explorers, and Mexican settlers. One of the few live-water sources in the parched terrain that lies between the Rio Grande and the Nueces River, the San Pedro still flows to this day, thanks to careful grazing management and vigilant attention to the health of native grasses and forbs.

“I see that spring as symbolic. I don’t want it going dry on my watch,” Fitzsimons says.

Fitzsimons and his sister are both conservationists: He is an avid quail hunter and she is a butterfly enthusiast. The San Pedro’s 36 soil types and plant communities host a wealth of rare species, including the Texas tortoise and the Texas horned lizard. The brother-sister team sees selective grazing and wildlife management as complimentary management tools. A registered Beefmaster herd and wildlife generate most of the revenues.

The results of their committed stewardship speak for themselves. In 2005, the San Pedro won the Outstanding Rangeland Stewardship Award from the Society for Range Management. In 2016, the ranch was recognized yet again, this time with the Lone Star Land Steward Award. Most recently, the Sand County Foundation bestowed its prestigious Leopold Conservation Award in 2020.

SPANISH LAND GRANT. Centuries old, the historic ranch was a critical landmark for conquistadors and other explorers thanks to its precious waters.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission

Governor Rick Perry appointed Fitzsimons to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission for a six-year term in 2001. Two years later, Fitzsimons’s status was upgraded to chairman. It was during his tenure on the commission that he learned the often tenuous history of the department. Texas Parks & Wildlife Department (TPWD) traces its founding to 1923. By the early 1960s, however, the state agency was on life support. After labeling the park system “sick to the point of dying,” Governor John Connally initiated and championed the only bond issue ever passed for park funding in Texas history. The results were immediate and telling.

Between 1963 and 1988, TPWD developed more than 70 parks, but funding didn’t keep pace with increased public use. An $800 million backlog of repairs accrued. Then Hurricane Harvey slammed the Gulf Coast; Texas parks were walloped.

To tackle this mountain of deferred maintenance, Fitzsimons and Dan Allen Hughes Jr., another former chair of Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission, launched the Texas Coalition for State Parks in 2018.

“When we started the coalition, there was no permanently dedicated funding for our state-parks system. We felt we owed it to the people of Texas, and to those who built those parks in the first place, to take care of what we already had. To that end, we brought together 72 organizations — landowners, hunters, anglers, retailers, and environmental groups,” he says. On Election Day 2019, Proposition 5, which fully funded TPWD, passed with 88 percent of the vote.

Centennial Parks Conservation Fund

Backlog addressed, park advocates pivoted to the future of the park system. During the 88th Legislature, the Texas Coalition for State Parks rallied support for the $1 billion Centennial Parks Conservation Fund. Texans passed this initiative on November 7 by a decisive 76-24 percent margin.

“That’s where the vision of people like Chairman Beaver Aplin and his commission, with strong supporters in the legislature, made a huge difference. George Bristol, Andy Sansom, and Carter Smith worked on this issue for decades. Watching their years of hard work finally come to fruition with the passage of the Centennial Parks Conservation Fund was deeply gratifying. Thankfully, a very deep bench of supporters in our legislative leadership came forward to ensure that Texas will have a state-parks system we can be proud of,” Fitzsimons says.

He wisely believes that parklands offer that rarest of opportunities in this day and age: common ground.

“In a time when there is so much disagreement and acrimony in our politics, it was encouraging to work on something we could all agree on. It can be done,” the South Texan says.

This story has been updated with additional developments.

NUMEROUS HONORS. Stewardship of the San Pedro is an ingrained tradition. In 2005, it won the Outstanding Rangeland Stewardship Award from the Texas Society for Range Management. A Lone Star Land Steward Award came in 2016. In 2020, the Sand County Foundation bestowed the Leopold Conservation Award.