Stefan Soloviev Goes Against the Grain

Stefan Soloviev Goes Against the Grain

By Lisa Martin

LR_StefanSoloviev-01-1

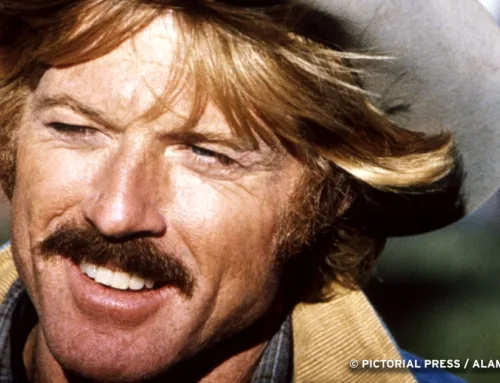

THE ICONOCLAST. Stefan Soloviev has bucked convention and built an agricultural powerhouse out west.

Stefan Soloviev moves like an athlete but has a mathlete’s mind for numbers. He’ll turn 50 in May but looks a decade younger. This native New Yorker, a true son of the city who Rollerbladed through Central Park on his way to high school, feels equally at home on the massive rural tracts he owns in Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico. Without fanfare or fuss, he’s positioned himself to take on the behemoths of corporate agriculture with an eye toward boosting local farmers’ bottom lines.

In a culture that rewards oversharing and self-promotion, he is forging his own path as he learns, grows, and makes moves that might surprise anyone outside of his tight-knit circle. Twenty-five years after his first purchase of farmland — 309 acres south of Wichita, Kansas, bought during a stint as a day trader in 1999 — Soloviev has become one of the top landowners in the United States.

In 2024, his holdings swelled to 617,000 acres.

“He’s a very humble guy,” says fellow Land Report 100er Shannon Kizer. “He’s a down-to-earth, good man, but he’s also the kind of guy that if you give him a million dollars, he’s going to try to figure out how to make $10 million with it instead of worrying about how to spend the million.”

That mindset was undoubtedly influenced by his father. For the first 15 years of his life, Soloviev was the only child and heir apparent of Sheldon Solow (1928–2020), one of Manhattan’s best-known real estate developers. Born in Brooklyn to Russian immigrants, Solow bought his first apartment building in Far Rockaway in 1950. Two decades later, he built 9 West 57th Street. One of the world’s most prestigious addresses, it overlooks the Plaza Hotel and Central Park. Along the way, Solow gained a reputation as being difficult and litigious.

“He’d be up all night reading papers, and I was assuming he was working on the company to make it better, but it actually had to do with his ‘hobby,’ as I call it, of suing people,” says Soloviev, who adopted the original spelling of his family’s last name as a way to distance himself from his dad. “He really was a lawyer at heart.”

SCALE AND EFFICIENCY. Soloviev has spent decades building a pioneering dryland farming and ranching operation in Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico (shown here).

A Born Trader

Soloviev, meanwhile, is a born trader. Starting around age 10 or 11, he spent hours decoding various stocks and commodities in daily newspapers and determining where to invest. He spent a couple of years at the University of Rhode Island before transferring his junior year to St. John’s University, close to where he grew up, to join their Division I-AA football team. After six months and a sports injury, he quit school and joined the Solow Building Corporation full time.

He quickly went from parking cars to running the entire garage operation. Yet he felt a growing frustration with his father’s combative approach to business. At 22, Soloviev and his 19-year-old wife, Stacey, moved out west and settled in Phoenix, Arizona.

“I would have stocked shelves at a grocery store,” Soloviev says. “I just wanted to get out of New York and be in a place where no one knew who I was.”

But Solow’s apartment buildings were underperforming. Soloviev went a year without speaking to his father, who continuously lobbied his older son to return to the fold. (At the time, Soloviev’s younger brother, Nikolai, was just in elementary school.)

Four years after heading west, Soloviev moved his family back to the East Coast after extracting assurances from his father that he’d have autonomy over the six garages and the residential properties. He quickly boosted occupancy at the 1,500 apartments in the five Solow-owned towers. The young executive also initiated improvements to the structures themselves, which was always a source of contention with his father.

But the West and the freedom it represented still retained a firm grip on Soloviev’s heart and mind, and he began to buy farmland on a large scale under the banner of his company, Crossroads Agriculture. “I’ve always loved farming,” he says, recalling a childhood fascination with the potato farms prevalent on eastern Long Island.

WINDSHIELD TIME. Jarryd Burris, Shannon Kizer, and Stefan Soloviev talk land a dozen years ago outside Causey, New Mexico.

Learning About Land

The learning curve of landownership only fueled his interest. “I had no idea that wheat was planted in November, went dormant in the winter, and then was harvested in June,” he says. He credits several farmers in Kansas for graciously helping to educate him.

“It’s a lot to learn, but I loved it. I loved the machinery. I couldn’t fix anything if my life depended on it, but it always intrigued me that you could produce a commodity that would then equal a contract traded in Chicago,” he says.

Railroads are another passion of Soloviev’s. The Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) Southern Transcon route ran through one of his first farm properties. Even then, he had a premonition that railroads and railways could play a role in furthering his ambitions.

Going to Nebraska

As his complex relationship with his father grew increasingly fraught, Soloviev turned his attention to a new opportunity: Nebraska farmland.

“I wanted land in a windy place where I knew there’d be turbines one day,” he says, anticipating the rise of the clean-energy movement. He used the sale of his Wichita-area properties to finance the purchase of dryland in Kimball County and irrigated land in Scottsbluff 50 miles to the north. Twenty years later, he readily admits the venture was a misstep.

“I thought I knew more than I did, and it didn’t work out or fit the overall picture. I’m not afraid to say I flat out failed in Scottsbluff,” he says.

Fast-forward to 2023: Soloviev’s premonition about renewable energy ultimately paid off when he executed a lucrative wind lease in New Mexico with a renewable-energy company in what is likely the largest deal of its kind to date nationwide. He already has 30-plus wind turbines constructed and operating on his farmland, with construction pending for many more.

After his Nebraska debacle, Soloviev decided to return to Kansas. He used a 1031 exchange to start acquiring farm acreage in the western part of the state and also in Colorado. An iconoclast through and through, Soloviev abandoned the typical practice of using section numbers to identify tracts and gave his fields familiar names.

“In Greeley County, Kansas, where we picked up a lot of land at first, I used all the streets in my home neighborhood: Apaquogue, Jones, Cottage, Lee, Jericho, Georgica,” he explains. “Every time I say the name of a field, I can picture the plat map and know exactly where the land is.”

Despite his skyrocketing acreage numbers, Soloviev can recite yields on his farms off the top of his head thanks to this unique naming convention.

RIGHT-HAND MAN. In 2005, Soloviev befriended Jarryd Burris, a neighboring rancher in Eastern New Mexico. Today, Burris runs Crossroad Ag’s South Region.

The Neighbor

Jarryd Burris bought his first farm in Eastern New Mexico in 2005. Next thing he knew, some New Yorker had purchased all the land around him. The two began talking cattle, wheat, and weather. Then they created a plan for trading cattle depending on rainfall and grazing. It proved profitable. Burris soon found himself running the entire South Region of Soloviev’s Crossroads Agriculture, the company’s largest by acreage.

“He and I are close enough in age, but we come from two extremely different backgrounds,” Burris says. “He never personifies a rich person or an elitist, and he really respects our Southwestern way of life. He is every bit the boss man, but we’ve become extremely close.”

“Our vision is to take the cow from birth to slaughter to the end user. My guys in New Mexico, led by Jarryd, are the absolute best and will get us there,” Soloviev says.

Soloviev spent a decade buying New Mexico cropland at an average price of $300 an acre. He scooped up better bargains at auctions in Colorado and Kansas. He keeps a close eye on the bottom line. “Stefan’s not wasteful, and he’s a very savvy investor,” Kizer says. “When it comes to land, he knows what he wants, and he has the vision to buy sight unseen but never above market value.”

Occasionally, the two partner on ventures. They stay in constant contact. Over dinner, they might talk about a particular property or compare interest rates offered by area bankers. They freely share opinions and rely on each other’s counsel.

“We complement each other,” says Kizer, who owns 431,000 acres, much of it near his hometown of Portales, New Mexico.

Soloviev credits Burris and Kizer with the assembly of the more than 15 parcels that form his Quintin City Ranch, which is named for Soloviev’s closest confidant, one of his adult sons.

NEXT LEVEL. Quintin Soloviev, shown here with one of his drones at Weskan’s Sheridan Lake facility, brings cutting-edge technical expertise to Crossroads Agriculture. Photograph by Chip Sherman.

The Confidant

Quintin Soloviev, 21, became vice chairman of the Soloviev Group in 2022. Five years before that, he started creating content for QFS Aviation, a personal YouTube channel where he documents commercial aviation activity.

“The difference between Quintin and me is that I was brought up specifically to work for my father, and Quintin’s been brought up to do what he wants as long as he’s productive,” says Soloviev.

“Quintin works very hard for me, but he’s also an artist, and I can see that in him. Like all my kids, I want him to feel no pressure to work for me. I want him to pursue whatever he is interested in,” he adds.

The family now makes its home in Delray Beach, Florida; the state’s business-friendly climate has spurred plans to develop agricultural projects there. “I believe in Florida. I’m proud to call it home now,” Soloviev says.

Father and son travel together on a regular basis to Colorado, Kansas, and New Mexico, a long-standing tradition that dates to Quintin’s childhood. Soloviev believes that asking questions and listening to responses drives success, a trait he has instilled in his son.

On their trips together, the two have standing meetings with managers. They review activity. Every effort is made to meet other operators in the area. Currently, the company has more than 50 tenant farmers. Many of them responded to newspaper ads the Soloviev Group took out that invited young farmers to apply for long-term leases on its farmland. Personal visits with their tenants are an integral part of these tours.

Revitalizing Railroads

A decade ago, Soloviev realized that a lack of choices on the western edge of the High Plains was limiting not just his bottom line but the incomes of most other producers too. So he decided to challenge the status quo by banding together with his fellow farmers.

At the time, the Colorado Pacific Railroad (CoPac) was to be demolished. The 120-mile line runs from the Kansas state line across the plains of Eastern Colorado to the foothills of the Rockies. CoPac offers something rare for the region: access to both BNSF and UP connecting services, a boon for smaller farmers. So Soloviev went to court to prevent the demolition. In 2018, he won a lengthy (and costly) legal battle in Washington, D.C., to acquire CoPac’s Towner segment.

Five years later, in 2023, Soloviev acquired a second short line, the 150-mile Colorado Pacific Rio Grande Railroad, out of bankruptcy. This line runs from the I-25 corridor over the Front Range of the Rockies to the San Luis Valley, the second-largest potato growing region in the nation.

With the help of COO Jason Jones, Soloviev took the Colorado Pacific Rio Grande Railroad from bankruptcy to profitability in less than two years. He plans to add additional short lines to his western railroad holdings. Soloviev is also challenging the major rail lines in court. He recently filed a complaint about a competing Kansas line’s “paper barrier” before that state’s Surface Transportation Board in an effort to bring grain marketing costs down for grain growers.

Soloviev’s revival of these two key rail lines has led other railroads to lower freight rates for farmers shipping grain to the Texas Gulf Coast, Mexico, or the Pacific Northwest.

To further his quest of connecting the dots at Crossroads Ag, Soloviev opened a new bulk, train-loading grain facility in 2022 near Sheridan Lake, Colorado. Weskan Grain now anchors his company’s North Division.

“Weskan is personal because I was a farmer there for 15 years, and I know what farmers are going through,” Soloviev says. The elevator runs alongside his Colorado Pacific Railroad. Once again, Soloviev made personal pitches to farmers, emphasizing how Weskan could help them keep more money in their pockets. Once again, he met with skepticism.

The tide began turning when High Plains farmers who entrusted him with their grain started singing Weskan’s praises. Because Weskan ships out unit trains — 110-car trainloads of the same grain — it obtains lower rail tariffs and can share those savings. Thus, it increases the profits of farm shippers.

In March 2024, Soloviev went a step further when he bought Stockholm Grain. This boosted Weskan’s capacity to approximately 15 million bushels. “With Weskan Grain, we found a buyer who shares our core values of being customer- and community-focused and being successful when the customer is successful,” said Ab Smith, CEO of Stockholm Grain at the time of the deal.

Another recent venture is Soloviev Ag Land Advisors, which capitalizes on Soloviev’s considerable expertise investing in agricultural landholdings. The company offers comprehensive advisory services to clients on all aspects of agricultural investments with a strategic focus on deploying capital in the Midwest, the South, and the West Coast. To honor the commitment Soloviev made to farmers, the firm has vowed to avoid transactions in regions served by Weskan Grain.

Meanwhile, in his South Region, Soloviev’s cattle operation keeps expanding. Corn and alfalfa grown in Kansas and Colorado now support the new feed yard at Quintin City Ranch where Soloviev maintains about 5,000 head — mostly Black Angus. He and his team have set their sights on raising that number to at least 7,500 head.

“Stefan always maximizes every effort we make,” Burris says. Soloviev is inching closer to his vision of consumers one day buying his own branded beef.

At the end of 2024, the Quintin City crew unveiled a state-of-the-art steam flaker that removes the hard shell from the corn to improve a cow’s digestion. The investment will help further the goal of finishing the cows at around 1,300 pounds apiece. Soloviev has another herd of about 2,000 head grazing on grassland and milo in Colorado that’s being supervised by his longtime farm manager Jacob Fehr.

After Soloviev stopped farming, he rented out his ground to local producers. Fehr became his biggest tenant. He also remains a key adviser. “I have always said in life there’s only a few real friends that will ever do anything and everything for you. Stefan has been a real friend to me and my family,” Fehr says.

Next Steps

In the meantime, Soloviev juggles the demands of the New York City real estate empire that he inherited from his father in 2020. Thanks to improvements he instituted at 9 West 57th, he tripled occupancy to 97 percent at the landmark property. The foundation he leads has contributed millions of dollars to charitable endeavors that range from child protection to wounded warriors.

In the next five years, Soloviev expects Weskan Grain to compete effectively with the titans of the dryland-grain merchandising business out west. Yet as he discusses the multibillion-dollar future of his conglomerate, he inevitably circles back to his commitment to small farmers. In Soloviev’s world, doing well and doing good go hand in hand, even as he owns up to some trial and error along the way.

“I’ve taken my lumps here and there, but I’ve never stopped learning from them, and I’ll never stop improving my business,” Soloviev told The Land Report in 2016 — a statement that still rings true today. “I don’t have the personality to ever be satisfied, and I honestly don’t see how anyone ever can be.

“You get nothing being complacent in life.”

QUINTIN CITY FEED YARD. A finishing weight of 1,300 pounds per head is the target.

Published in The Land Report Winter 2024.