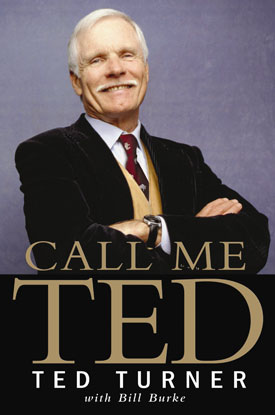

Ted Turner Tops the 2008 Land Report 100

Ted Turner Tops the 2008 Land Report 100

For the second year in a row, Ted Turner take top honors as America’s largest landowner with more than a dozen properties totaling more than 2 million acres.

Add to this more than 100,000 acres in Argentina, where he owns two estancias in Patagonia and one in Tierra del Fuego, and the media mogul’s holdings are an empire unto to themselves, ranking larger than 48th state, Delaware.

Here, in a Land Report exclusive, is an excerpt from his recently published memoir, Call Me Ted, is the story of how he went about creating Turner Ranches, an entity that dates back to his acquisition of Montana’s Bar None Ranch.

After buying the Bar None Ranch and spending increasing amounts of time in Montana, I fell even more in love with the area. When I enjoy something, I have a tendency to overdo it, and when I was told that a larger ranch was coming on the market, I was interested. Jane and I were still getting used to the scale of the Bar None when I told her that now I was going to look into a property that was many times larger.

The Flying D Ranch is more than 119,000 acres, situated between the Gallatin and Madison Rivers. It’s a beautiful property with good trout streams and it had a lot of pasture that would be perfect for a large bison herd. Jane thought I was crazy but for $21 million (or about $200 an acre) it seemed like it would not only be a great place, but also a terrific investment. I bought it in 1989.

Like most large ranches, the Flying D contained a lot of signs of human impact, like power lines and poles and barbwire fences. One of the first things I wanted to do was get rid of all this junk and barbed wire. My goal was to restore the property to what it would have looked like 150 years earlier, before the white man came. It was a lot of work, but we removed just about every sign of human disturbance, save the dirt and gravel roads.

Part of my desire to own this land was to make sure that it was never developed. Conserving this property for future generations seemed like the right thing to do, especially with so much development happening in that part of the country. I worked out a conservation easement with the Nature Conservancy that guarantees to repopulate the property with bison, an animal that I’d been fascinated by for two years. I purchased my first bison back in the 1970s – a bull and two cows – and kept them at Hope Plantation (where I also had been raising and breeding bears, cougars, and other animals that had been native to that area in earlier days).

I knew that the bison population had once numbered in the tens of millions before dropping to below a thousand, and for the Flying D to look like it looked hundreds of years before, we needed a large her.

During my early years of ranch ownership, my enthusiasm did lead me to make some mistakes. For example, the Flying D had hundreds of miles of barbed wire fencing and I had every bit of it removed, thinking this would allow the bison to roam free on about eighty thousand acres. I learned that when you do this, the animals tend to overgraze certain areas and undergraze others, and we had to bring back some limited fencing – not barbwire, I might add.

The Bar None and the Flying D gave me so much pleasure that I decided to buy as many large properties as I could reasonably afford. By the end of the 1990s, I had purchased two more ranches in Montana, three in Nebraska, one in Kansas, and one in South Dakota (they’re used primarily for bison ranching).

Then between 1992 and 1996, I bought three large ranches in New Mexico. The biggest, Vermejo Park, is nearly 600,000 acres, and together these three ranches cover more than one million acres. They are also used for bison ranching, as well as hunting and fishing, and Vermejo sits on top of valuable natural gas that is being extracted by an energy company that has the rights. They do this work very carefully, extracting the gas while protecting the ranch’s beauty and wildlife.

I’ve also enjoyed working on the return and protection of threatened and endangered species. In addition to bison (of which we now have about 45,000 head), we’ve worked to reintroduce about twenty other species. These include gray wolves, red-cockaded woodpeckers, and black-footed ferrets. These were all challenging projects so I looked for the best people I could to help manage the properties.

I hired Russ Miller in 1989 and he’s been with me ever since, doing a terrific job as general manager of the ranches. In 1997 I created the Turner Endangered Species Fund, recruiting Mike Phillips (who led the effort to bring back the gray wolf to Yellowstone) to run the organization, along with my son Beau, who studied wildlife management at Montana State University after graduating from The Citadel.

In Montana, I learned to love fly-fishing. It’s one of the few things I do that’s not only interesting and challenging but also relaxing. Unfortunately, it’s not a sport you can enjoy during a Montana winter (except on rare occasions), but I learned that there are rivers and areas in the Patagonia region of Argentina that are similar to Montana. Since South America is counterseasonal to the United States, I could fish there during the North American winter. In ’97, I purchased a nine-thousand-acre ranch in Patagonia named La Primavera, and in 2000, a 93,000-acre property named Collon Cura. I also bought a 24,000-acre ranch and fishing lodge on the island of Tierra del Fuego. These three properties all feature great fly-fishing.

Subsequently, I acquired two more ranches on the Great Plains of Nebraska and one in Oklahoma, primarily for raising bison. Today, with over 2 million acres, I’m the largest individual landowner in the United States. We operate our ranches responsibly from an environmental viewpoint and also have an outfitting business that allows hunters and fishermen to use our properties on a limited basis. With revenues from bison sales, some controlled forestry, energy leases, and private hunting and fishing, the ranches turn a small profit.

Owning the properties has given me tremendous pleasure. My connection to nature goes back to my early childhood when I spent hours outdoors either alone or with Jimmy Brown. I’d fish, gig for frogs, or just observe the wildlife around me and these times helped me through a lot of loneliness and gave me great peace of mind. Being outdoors is my chance to unwind, clear my head, and think. The time I spend in nature refreshes and recharges me and reminds me how much raw beauty exists in the world – and how careful we should be to preserve it. The ranches are also great places for me to spend time with friends.

On nearly every trip I make in the United States or Argentina, I invite friends and family. I’ve also hosted business colleagues and world leaders. (I’m proud to say that three Nobel Peace Prize winners have been among my houseguests – Mikhail Gorbachev, Jimmy Carter, and former UN secretary-general Kofi Annan.) I also enjoy observing and interacting with nature and it’s a special feeling to be part of the natural environment.

One of my favorite experiences involves a bird I befriended several years ago at my Snow Crest Ranch in Montana. It was a baby magpie that had fallen out of its nest and was lying on the ground. My house staff and I pulled together a box, some paper towels, and an eyedropper, and gave it food and water. The little magpie responded and we pulled him through.

In the process we bonded, and I named him Harry. We bought a traveling cage for him and took him with us when we moved from one ranch to another. He learned to talk and would up providing great entertainment. We would let him out of the cage during the day and he’d follow me around.

When I’m at a ranch I get a FedEx package from my office of the previous day’s mail. With Harry, I’d sit on my couch reading my mail and once I was through, I’d crush the pages into a ball and throw them on the ground for Harry to play with. He charmed everyone (including Gorbachev – he sat next to his coffee cup one morning at breakfast and gave him a couple of light pecks on his famous forehead). Harry became a little too feisty and ran into trouble when he started dive-bombing people and we were concerned that he might put someone’s eye out. We decided we had to take Harry to the Beartooth Nature Center in Red Lodge, Montana. He still lives there, and to this day, whenever I see magpies flying overhead, I think of my old pal Harry.

I’m proud of the work we’ve done to preserve and protect the properties and I’ve tried to do everything I can to make sure that they’re maintained after I’m gone. With my passing the properties will be protected by conservation easements. In certain parts of the country, my rancher neighbors have grown suspicious of me and created theories about ulterior motives I might have, going so far as to speculate that I might be trying to tie up and control water rights for entire regions. None of this is true. As long as the conservation laws of the United States remain in place, the land will be protected from development in perpetuity (and we’ve taken similar measure with the Argentine properties).

I’m often reminded of Scarlett O’Hara’s father in Gone With the Wind, who told her, “Why, land’s the only thing in the world worth working for, worth fighting for, worth dying for, because it’s the only thing that lasts.” I’ve realize this to be true, and I’m proud to know that I’ve done what I can to make sure that my land is protected.

You can purchase a copy of Call Me Ted by visiting Amazon.com