The Gualala Redwoods Story

The Gualala Redwoods Story

By Corinne Gaffner Garcia

GualalaRedwoods_fi

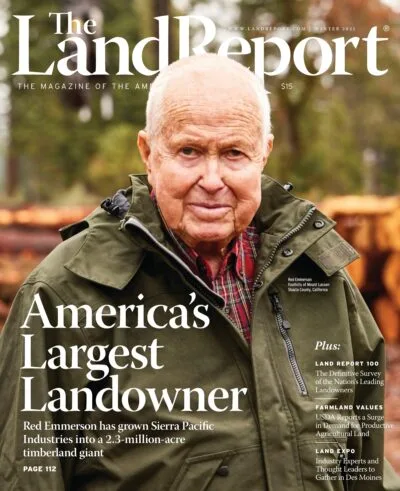

REDWOOD COUNTRY. Northern California's coastal climate nurtures the rot-resistant, disease-resistant giant.

The people of Gualala, a quaint coastal town some three hours north of San Francisco, know well the fog that rolls in off the Pacific Ocean. So did their predecessors, the Kashaya Pomo Indians.

“The water coming down place” is the Pomoan name these Native Americans christened the stunning setting where the mouth of the Gualala River meets the cold ocean waters and the coastal fog seeps into the nearby forestlands, covering them like a fluffy blanket.

Home of the California Redwood

The millions of acres of forestland that surround Gualala are home to the tallest tree on earth, the California redwood. Sequoia sempervirens does more than thrive on this thick coastal fog. It actually needs the smoky vapor to grow as tall as a 30-story building (360 feet). Although the average redwood lives 500 to 700 years, ancient ones reach back to the days of Caesar. Another singular quality of this species is that new trees will sprout from the stumps of ones that have been felled.

Beginning in the 1860s, the timber industry was the economic mainstay of Gualala, and it would remain so for more than a century.

Thanks to its natural acidic tannins, the redwood is rot-resistant, disease-resistant, and incredibly strong. Its value as a timber product is unmatched. Much of San Francisco’s early infrastructure was built with this magnificent tree, and, after the earthquake and fire of 1906, it was rebuilt with redwood.

This unique tree has shaped Gualala’s history, from the days of the Kashaya Pomo to its rise as a logging and sawmill hub in the 1860s to the late 1940s when three Floridians recognized its sterling qualities.

A Florida Partnership

J. Ollie Edmunds Sr., Sigurd Fogelberg, and Sherwood Hall had offices in the same Jacksonville bank building. During the Great Depression, the three began investing in Northeastern Florida timberland whose owners were unable to pay property taxes. Fogelberg and Hall were foresters. A lawyer and judge, Edmunds enjoys the distinction of being the sole alumnus of Stetson University to serve as president of his alma mater. Two factors motivated the trio: the economic realities of the times and a passion for the great outdoors.

In the aftermath of the Stock Market Crash of 1929, timberland was recognized as a rock-solid asset with strong upside potential. One of Hall’s most famous clients, Alfred I. DuPont, charged him with finding potential timberland investments both in-state and out of state. (DuPont’s vast Florida holdings would become the foundation of the St. Joe Company.)

“Hall found the 30,000-acre Gualala Redwoods and fell in love with it,” recalls J. Ollie Edmunds Jr., M.D. “He went back and told Mr. DuPont, who turned it down. But Mr. DuPont encouraged the others to buy it, which they did.”

The three formed a general partnership, with Hall staying on as resident partner and the others returning back East to pursue their careers. They formed a timber management company to work the land, but the partners remained hands-on, ensuring it was always well-managed. The timber tract became a family affair, especially for the Edmunds children, Ollie and Jane, who would stay in the bunkhouse above the offices.

Connection to the Land

“My fondest memories are of being out in the woods with Dad, just walking through the forest and being together,” Ollie says. “We spent a lot of time on the land, and this was the reason my dad and I became so close. He became my mentor.”

Walking amidst the towering redwood trees was like a religious experience for Ollie and his father. The connection they developed to this landscape ran deep. When Ollie’s mother passed away, his father took a year off from the presidency of Stetson. He went to Gualala to clear his mind. Then he returned to his post.

While in college, Ollie transferred from Washington and Lee to Stanford in order to become more familiar with the redwood timber business. On his vacations, he worked on a surveying crew as the pole-and-ax man. He lived in the Gualala bunkhouse. He and his father even discussed going to forestry school together. Ollie had caught timber fever and acquired his father’s passion for the business and the land.

Ollie Takes the Reins

But instead of forestry, Ollie went to medical school and became an orthopaedic surgeon. Since 1976, he has been a professor of orthopaedic surgery at Tulane University School of Medicine in New Orleans as well as chief of hand surgery.

But his love of the land didn’t fade. He acquired 8,000 acres of Louisiana timberland. Following his father’s death, he became CEO and chairman of Gualala Redwoods. To prepare for this endeavor, he enrolled at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and studied accounting, finance, and mergers and acquisitions.

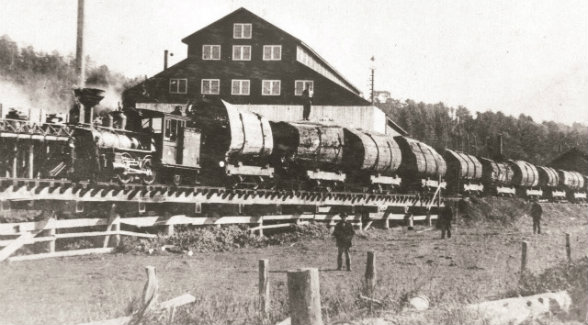

In the 1800s, log trains such as this one hauled a single old-growth redwood per railroad car to the sawmill in Gualala. Redwoods built San Francisco, then rebuilt it after the Great Earthquake and Fire of 1906.

“I would advise leaders of closely held family companies and other CEOs to do some homework,” Ollie says. “When I became CEO and chairman, I had to study accounting, which they never taught me in medical school, so I could read financial statements and cash flow reports.” He attributes much of the financial success of Gualala Redwoods to this prowess.

“While I was practicing orthopaedic surgery, I only made it out to Gualala about once a year,” Ollie says. “My management firm, Delta Pacific Inc., has outstanding foresters, and I meet by phone with my senior forester usually each week.”

Even if he wasn’t there in person, the redwoods were always on his mind. “My wife thinks of Gualala Redwoods as more of a mistress,” Ollie says. “It’s something I feel extremely passionate about.”

Every year, Ollie and his foresters tour Gualala Redwoods by helicopter. “We pay particular attention to our harvested areas. It’s amazing to me how fast the trees in these plantations grow, and how well stocked and green the harvested areas are,” he says.

A Delicate Balance

Balancing timber management and the environment is a trait passed down from father to son. “We make the forest better than when we harvested trees,” Ollie says. “The redwood stumps sprout new growth. We also interplant, cultivating seedlings from the best trees on the property and increasing the stocking per acre. We grow more volume of trees than we harvest annually.”

Well-maintained roads diminish sediment runoff and keep surrounding streams and rivers healthy and clear. Cull logs placed in waterways enhance fisheries. Thanks to these efforts, and many others, Gualala Redwoods was honored when the Gualala River Watershed Council received the first annual Watershed Stewardship Award from the North Coast Water Quality Control Board.

“We’ve taken strides to protect Gualala Redwoods for our children and our grandchildren,” Ollie says. He pauses momentarily. “And now we’re selling it to a new generation of people. They’re going to have something better than what our family bought.”

A Tourist Destination

Gualala has also evolved, transforming itself from a timber center to a tourist destination. New hotels have opened for business. So have shops and restaurants. The Sea Ranch subdivision is a prime example of this growth spurt, drawing in second homeowners from near and far. Gualala Redwoods has bolstered this trend by donating 11 acres of prime Gualala River frontage and redwood timber to Gualala Arts for its impressive arts center.

In honor of Ollie’s father, Ollie and his sister, Jane Edmunds Novak, established and support the J. Ollie Edmunds Distinguished Scholarship at Stetson. It awards four-year full-ride scholarships to exceptional students. Ollie also supports lectureships at Duke, Tulane, and the Orthopaedic Research and Education Foundation.

Ollie credits his father with stressing the importance of giving back to the land and the communities that helped shape them. “He was really passionate about it, and he passed those values down to me. I’m trying to pass down the values of philanthropy and noblesse oblige to my children,” Ollie says.

“Gualala Redwoods has been a positive experience for our Edmunds family, both financially and emotionally. We have been afforded many educational opportunities. Most importantly, we have enjoyed many memorable occasions as a family unit, which have brought us together and created a strong family bond. Selling this land is especially bittersweet for my sister and me, but it feels good knowing that we protected the environment and that it’s better stocked with trees than it was 66 years ago.”

Editor’s Note: After publication, Gualala Redwoods was purchased by Pacific States Industries.

Published in The Land Report Fall 2014.