Snake in the Grass

Snake in the Grass

By Emily Payne

LR_SnakeintheGrass-PropertyRights-01-01

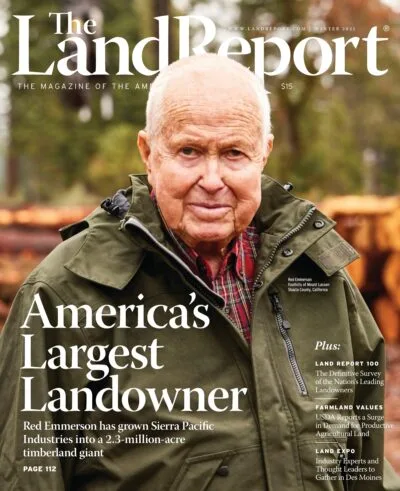

THE ELUSIVE INSTIGATOR. A black pinesnake rests at Camp Shelby Joint Forces Training Center, a Mississippi National Guard camp with parts in the De Soto National Forest.

In 2015, Gray Skipper was informed that 30,000 acres of his family’s timberland in Southwest Alabama was considered critical habitat for the black pinesnake, a species that neither he nor any of his relatives had ever seen on their property. His first reaction was confusion. Anger quickly followed.

“We had a lot of questions, but the first one was, ‘How do you designate 30,000 acres based on one credible sighting?’ ” Skipper asks. “Then I remember getting pissed off.”

Opposite Effect

According to the lawsuit that Skipper and the Forest Landowners Association (FLA) subsequently filed in federal court, the US Fish & Wildlife Service designated the Skipper family’s land as critical habitat for the black pinesnake based on a single sighting of Pituophis melanoleucus lodingi in the previous 20 years. The lawsuit argued the designation was arbitrary, lacked scientific basis, and caused economic harm with little evidence of environmental benefit for the black pinesnake, which had recently been listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

“We were managing the land exactly how [US Fish & Wildlife Service] wanted, but then they designated the snake as threatened and put restrictions on our property. That put us in a corner. We didn’t ask to be in that corner,” says Skipper.

Skipper says the critical habitat designation did the opposite of its stated intention: Once the Skippers’ lands were designated critical habitat, they were compelled to withdraw them from a long-standing land stewardship effort that had benefitted the public for more than a half-century. Earlier this year, Skipper’s family and the FLA won their federal lawsuit, yet both contend that it is merely the latest example of a broken conservation system.

A Legacy Of Conservation

Since 1888, Skipper’s extended family has owned and managed timberland in Southwest Alabama via Scotch Land Management. In 1956, the family’s Scotch Lumber Company leased approximately 20,000 acres to the State of Alabama at no cost for 50 years. The goal? To keep hunting affordable to the public. Known as the Scotch Wildlife Management Area (WMA), the state managed the area primarily for whitetailed deer and eastern wild turkeys and to support local hunters, according to Skipper.

“Hunting was a way of life. It was supposed to be for everyone who wanted to enjoy the land at minimal cost and to continue this family tradition for generations,” Skipper says.

The Skippers took pride in this legacy of active land stewardship, maintaining native habitat for numerous wildlife species and providing public recreational opportunities in Alabama’s vast timberlands. But in 2015, the US Fish & Wildlife Service issued a critical habitat designation for 90,000 acres of timberland in Alabama and Mississippi. To protect the Skipper family from hefty, six-figure fines or potentially even jail time for violating the Endangered Species Act, Scotch Land Management ended its WMA agreement with the Alabama Department of Conservation & Natural Resources.

No Scientific Evidence

A decade later, a federal judge ruled that the US Fish & Wildlife Service acted arbitrarily with regard to the designation of the Scotch lands. In essence, there was no scientific evidence to support the science. The US Fish & Wildlife Service dropped its critical habitat designation, but damage had already been done, says Forest Landowners Association CEO Scott Jones.

“[The Skippers] continue managing the land the way they were managing it. The only thing that’s happened is the public has lost out on this wildlife management area,” Jones says. “All the things the family did to try to increase and promote wildlife habitat in their area, and they turn around and get punished for that very thing.”

Unintended Consequences

According to the World Wildlife Fund’s 2024 Living Planet Report, global wildlife populations have declined by an average of 73 percent since 1970, affecting ecosystems and threatening clean air, clean water, and food production. In the United States, critical habitat designations — through the Endangered Species Act — aim to protect threatened or endangered species’ habitats while supporting recovery. Once a species is listed as threatened or endangered, the US Fish & Wildlife Service is required to designate the critical habitat needed to accomplish this.

Both Skipper and Jones find fault with the agency’s methodology. “[Skipper’s case] was the latest in a pattern of behavior. There was precedence that Fish and Wildlife was going out of their bounds,” Jones says.

Enter the Dusky Frog

The dusky gopher frog (pictured above) is a prominent instance of this trend. After the US Fish & Wildlife Service listed the species as endangered in 2001, the agency designated critical habitat at a site in St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana — an area where the dusky gopher frog had at one time populated but had not been sighted for 50 years. The land in question had belonged to the Poitevent family for more than 150 years and was leased to Weyerhaeuser for use as a commercial timber operation. The critical habitat designation had an immediate impact: It put an estimated $34 million in economic activity on hold.

The Poitevents and Weyerhaeuser filed suit. Weyerhaeuser Co. v. US Fish and Wildlife Service worked its way through the court system and ultimately ended up before the Supreme Court. In 2018, the justices unanimously ruled that the US Fish & Wildlife Service “illegally overstepped its authority with the critical habitat designation,” a big win for landowners, according to Jones.

Flawed Economic Analysis

The Scotch Land Management case was another win for landowners who assert that the US Fish & Wildlife Service routinely oversteps its bounds with critical wildlife designations. While the agency has historically argued that critical habitat designations have no economic impact on landowners unless they are working with federal funding or on a federal project, the US District Court for the Southern District of Alabama cited the agency’s flawed economic analysis.

“Designation of private land as critical habitat has an immediate impact on property value and potential development opportunities,” the court stated. “The record contains evidence that the mere presence of a critical habitat label can create a public perception of regulatory risk, leading to reduced market value of the land … the reduced value of Plaintiff’s land caused by the designation is a real economic harm.”

Jeff McCoy at the Pacific Legal Foundation believes that the black pinesnake case may promote more thoughtful decision-making by the US Fish & Wildlife Service. “We hope that we can set a precedent with cases like Skipper, where Fish & Wildlife will not be so hasty in designating land as critical habitat without doing what they’re required to do.”

Monitor and Comment

A senior attorney in Pacific Legal Foundation’s Property Rights practice, McCoy recommends that landowners pay close attention to the US Fish & Wildlife Service’s Environmental Conservation Online System to know whether critical habitat has been proposed in their region. The process of designating critical habitat requires a public comment period, during which landowners can make their voices heard.

“Make sure to comment and ensure that Fish & Wildlife knows the effects that designation would have. There’s discretion to exclude some areas from critical habitat, and if there was enough public comment that shows how that would negatively affect private landowners, that would add some pressure to exclude those areas,” McCoy says.

Scott Jones notes that individual landowners cannot always bear the onus by themselves. For Skipper, 10 years passed between the notice of potential critical habitat designation to when the designation was dropped. During that period, he and his family spent countless hours and invested substantial resources challenging the case and discussing it with business partners and legal advisers.

“It’s asking too much to say, ‘Here’s how you mitigate risk of a potential listing on your property. Get to know everybody at Fish & Wildlife in your region, state, and district,’” Jones says. Instead, he believes that the most effective shield is to participate with an organization that represents the interests of landowners with similar properties.

Strength in Numbers

Fortunately for Skipper, he was already dialed into several strong networks. He currently serves as a member of the FLA board of directors. The association’s 2,000 members own 55 million acres of land nationwide. FLA advocates for the economic interests of private forest landowners by promoting policies that support property rights, sustainable forest management, and the long-term viability of forest ownership.

Skipper also singles out the importance of regional associations, such as the Alabama Forestry Association, which promotes responsible forest management and sustainable forestry practices to benefit the environment and the economy. Numerous other local, state, and regional associations are available to landowners, depending on their location.

“Landowners should protect themselves by participating with an organization that is actively engaging and telling their stories to Fish & Wildlife and other agencies so that you can avoid unintended consequences of misinformed, nonscientific listings,” says Jones.

“You won’t find a minimum premium insurance out there that will give you more protection than paying dues into the right type of organization,” Jones says.

Published in The Land Report Fall 2025.