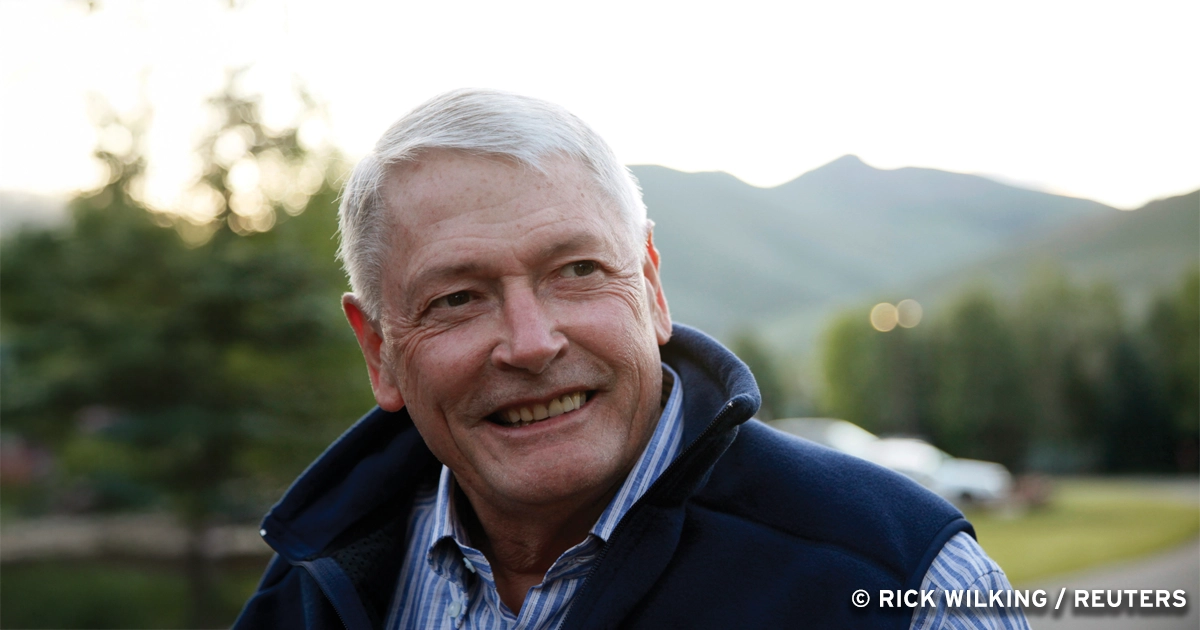

John Malone

Born to Be Wired Excerpt

John Malone

Born to Be Wired Excerpt

By John Malone

LR_JohnMalone-02

You can’t appreciate what a precious commodity open land is until you see it vanish over time. And then one day you look, and it’s gone. Forever.

When Leslie and I first moved to Denver some 50 years ago, we fell in love with the powder-dusted peaks of the Rockies, the cowboy culture, the clean air, and the freedom of the West.

We were mesmerized, like so many before us, by the infinite detail, texture, and color of the land that slopes up toward the Front Range. Out West, you can be swept away with the very same sense of physical freedom you feel on open water. The view connects you in a way that transcends the physical beauty of the place. You feel it.

We bought a ranch just to the southeast of the city limits and learned how to run a tractor, plow fields, paint barns, and plant oats. We didn’t own a boat so far inland, so we set about living a more Western lifestyle.

We learned a lot about cattle. We raised a white registered Charolais bull — a muscular breed originally from France raised around the world — and crossed it with a black Angus, hearty beef cattle from Scotland popular in the US, an effort to produce offspring that essentially grow faster and bigger and healthier, something known as “hybrid vigor.”

We had help, but it was all hands-on for us — moving cows in snowstorms, injecting penicillin into the shoulders of sick calves … even castrating steers. For me, it was a way to spend time with Leslie and to distract my brain from the stress at Tele-Communications Inc. (TCI) — a refreshing (and sometimes exhausting) change from the social pressures in the Northeast.

Bob Magness owned a ranch from the time I first knew him called the Hidden Valley Ranch, about 40 miles southwest of Denver and at pretty high elevation in the mountains. Up there, he would go to unwind, rub the silky necks of his Arabian horses, and entertain guests. Bob liked to say that once a banker had a few drinks at the ranch, especially at such high elevation, he would agree to damn near anything by the end of the evening.

It is where he and his first wife, Betsy, are buried now. I have not been to their graves in a while, I’m sure in part because I buried a small piece of myself up there when he died.

TCI bought its first company ranch in Encampment, Wyoming — Cow Creek Valley, a 22,000-acre spread just north of the Colorado border, in the late 1970s, which would become the original Silver Spur ranch. It was a working cattle ranch, but often TCI would hold meetings there with investors, suppliers, and politicians. When Bob died and TCI was sold to AT&T in 1998, I bought the ranch to keep it in the family.

And so my love affair with the land and the West started with Leslie during those early ranch days, grew stronger in my time with Bob, and became manifest later, during my days with Ted Turner.

We felt the West disappearing even back then. Over the years, Leslie and I moved three times because we felt the city encroaching on us. Even now, what used to be a pleasant 20-minute drive to the office now takes me an hour in traffic that feels more like Midtown Manhattan, depending on the hour of the day. And when I look up from my dash, all I can see are red tail-lights snaking through waves of concrete.

Open spaces: This pursuit will consume most of the material wealth that Leslie and I have built up in our lifetime, a key reason we formed the Malone Family Land Preservation Foundation. We will designate a vast portion of the 2.2 million acres in six states with a protected status that will ensure it stays natural and utterly undeveloped forever, and I hope to expand this even more. The foundation, run by Rye Austin, seeks investments where we can have a multiplier effect, either through matching funds or working cooperatively with preservationist groups or with local and state governments.

Though our first ranch in Denver is surrounded by development, I can’t imagine selling it. Every Coloradan deserves to see the state in its natural state.

By 2000, the concrete corridor along the 71-mile trek of I-25 from Denver south to Colorado Springs had grown so aggressively that the sprawl was close to meeting somewhere in the middle, completing an unbroken sea of commercial buildings, chain restaurants, and subdivisions in between — all the way to the base of the Rocky Mountains.

There was only one natural buffer in between that afforded uninterrupted views of the Front Range of the Rockies to the west. It is a view you could have witnessed easily from the same spot standing there 2,000 years ago: a 12- mile-long panorama of grasslands, mesas, and meadows, with elk, trout, and bear, leading up to the base of the majestic snow-crusted Pikes Peak.

COLORADO’S GREENLAND RANCH. John and Leslie Malone invested $78 million to protect this dramatic, 12-mile-long panorama below Pikes Peak.

The largest piece of the 21,000-acre spread is the Greenland Ranch, east of I-25; one of the longest-running cattle ranches in the country, dating back to 1900. When the 17,700-acre ranch went up for sale in 2000, we paid $55 million to take it off the market and prevent development. Working with the state of Colorado and The Conservation Fund, we contributed another $23 million to secure conservation easements from the sellers. Douglas County purchased the remaining land west of I-25 for open space.

By leveraging the like interests of partners and nearby landowners, we were able to preserve a bigger piece of land, with more-engaged caretakers than if I had gone in alone. Now the land is in a conservation easement and can never be developed.

Going forward, the Colorado Cattlemen’s Agricultural Land Trust will be the steward of the easement because we are trying to preserve something just as important as the land: Colorado’s culture. The developers called it a waste of badly needed space for a fast-growing city. I call it a permanent benefit, because in the end, we saved a sliver of Colorado that still looks like Colorado.

And it serves many beneficiaries. Aside from the carbon containment from undisturbed soil, the land supports a substantial wildlife population, including deer, elk, and bighorn sheep. And most parts are open to the public for hiking, biking, and even hunting, based on a licensing lottery.

From BORN TO BE WIRED: Lessons from a Lifetime Transforming Television, Wiring America for the Internet, and Growing Formula One, Discovery, SiriusXM, and the Atlanta Braves by John Malone. Copyright © 2025 by John Malone. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, LLC.