Wild Man: Wyman Meinzer

Wild Man: Wyman Meinzer

By Henry Chappell

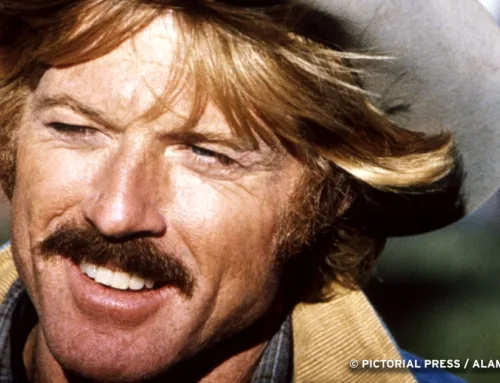

Wyman01_fi

Wyman Meinzer does more than study the ways of the Old West. The State Photographer of Texas regularly field-tests them, braving winter’s bite with a bison hide or handcrafting an honest-to-goodness dugout in the side of a creek bank.

I could write a book about Wyman Meinzer. The truth is, I’ve collaborated on four books with the guy, and I’m taking a break from our fifth to pen this profile. You might expect me to start off by telling you when I met him or where I met him or how I met him, but I think it best to begin by telling you when I first learned of this wild man.

In the early 1980s, I was stuck behind a desk holding down a corporate job in Dallas. Like a lot of jobs in gilded cages, the pay was good. But I spent a fair amount of time daydreaming about the great outdoors. Subscriptions to Field & Stream, Outdoor Life, and Sports Afield stoked this fever. Come hunting season, my idea of a great weekend was to load my dogs in the truck, drive all night, and arrive in the field by sunup.

One day back then, I was paging through American Hunter and started reading about this guy from another era. Like me, he had a college degree, but instead of wasting away in an office, he went off and spent several winters trapping coyotes and bobcats in the Big Empty, that immense swath of West Texas that is home to iconic ranches such as the Waggoner, the Four Sixes, and the Pitchfork. I can’t tell you how many times I read that article, savoring each photo and every word.

Turns out his name was Wyman Meinzer.

Hunter, trapper, naturalist, historian — Wyman came across like a throwback to a different era, a true-blue Teddy Roosevelt. In addition to his adventures on the Pitchfork, it turned out that he was an artist — one whose primary tool was a camera. I began looking for his photography credits and quickly learned that it was almost impossible to page through a national outdoor magazine without gawking at one of his too-close-for-comfort rattlesnake shots.

Several years later, articles by yours truly began to appear in regional and specialty magazines. In the early 1990s, when several of Wyman’s photos made a quail-hunting story of mine in Texas Parks & Wildlife look a lot more impressive than it was, it was a milestone for me. Although we’d never met, I hoped that Wyman might recognize my name, too.

Around that time, I was researching my first novel, The Callings. I poached Wyman’s email address off a note from one of our editors. I had read a Dallas Morning News story in which the reporter, the venerable Ray Sasser, mentioned Wyman’s passion for Sharps buffalo guns. With more curiosity than hope, I sent Wyman an email asking for suggestions on books featuring the great bison hunters. A few hours later, I received a friendly reply with a list of out-of-print titles that I had no idea existed.

More importantly, I would never have found them on my own. Whatever the flaws of my first historical novel, it’s not short on realistic details concerning the daily lives of the hide men, right down to their styles of skinning knives and methods of reclaiming bullets. I credit Wyman for that. Years later, I learned that Wyman’s approval of my manuscript contributed to The Callings’ acceptance and publication. Our brief back-and-forth was when I began to understand the depth of Wyman’s respect for the history and ways of the Old West. He corrected an embarrassing error in the narrative. I mistakenly listed cyanide as a wolf poison. “Strychnine,” he informed me.

A decade later, I found myself at the 2002 Texas Book Festival in Austin. From across a crowded room, I saw Judith Keeling, my editor at Texas Tech University Press. “Get over here! I’m negotiating on your behalf,” she yelled.

There, amidst a few hundred people dressed for a black-tie dinner, stood Wyman in his knee-high Russell boots, some unusually presentable jeans, and a fringed leather jacket. By his side, as always, was the beautiful Sylinda. She was sure enough dolled up for the festivities. Texas Tech planned to publish a work about the legendary Four Sixes Ranch. There had never been the slightest doubt as to the photographer. But the writer? That was still up in the air.

I walked up and shook hands with Wyman. Then we talked for a couple minutes. As I recall, some Austinites were bragging about the beauty and the general superiority of Austin in late October, and Wyman had had his fill.

“Lord, it was beautiful up home today. I sure as hell hated to leave and come down here,” he said. He made sure to say it loud enough for every provincial within 50 feet to hear. The three of us enjoyed a good laugh. Then Wyman turned to me. “You ‘bout ready to do this thing?” he asked.

Thus began an adventure that continues to this day.

Although he has probably done more than anyone else to bring great ranches to the public’s attention, cowboying never appealed to the Texas native. He and his younger brother, Rick, and their older sister, Patty, grew up on the League Ranch in Knox County. Their dad, Pate Meinzer, was foreman on the League.

“The signs came early,” Wyman says. “Once we were old enough to ride, we had to work every day. But I was always more interested in watching wildlife and searching for arrowheads than working cattle. By the time I was 15, I knew I wanted to work in wildlife. But I had no idea that I would be a photographer.”

When Wyman was seven, his grandfather, Gordon Cole, gave him a pair of 1½ Victors traps. “That was one of the greatest gifts I’ve ever received,” he says.

Throughout boyhood, he ran a trap line for skunks, raccoons, and possums. He got his first BB gun at five and a Stevens single-shot .410 at nine. Wyman still has that old Stevens and occasionally uses it.

Pate Meinzer often took the family coyote hunting at night. “We lived 11 miles out of town, so we weren’t going to movies or anything like that,” Wyman says.

“Dad would load up Mom, Rick, Patty, and me, and we’d hunt with nothing but a spotlight and a .22.”

Coyote fever hit for good when he was 14. He left a party to go hunting with his dad and brother. “When I got home late that night, I was worthless. All I could think about was coyote hunting.”

The first coyote he ever called?

“October 17, 1965. I was 14. It was 2:15 in the afternoon. I had a 30-30 Marlin with a Sears and Roebuck scope on it. I had two rounds to my name. I called two coyotes in at once. They broke and ran, and I shot the trailing coyote at 247 yards.”

It’s all there in his field notes. Since his early trapping days, Wyman has kept a detailed journal. As he grew into manhood, the embellished stories of his youth gave way to the meticulous notes of a disciplined naturalist.

His passion for the great outdoors and coyotes in particular led him to pursue a degree in wildlife management at Texas Tech. During his senior research project on coyote feeding habits, his principal professor loaned him a 35mm camera and suggested he take a few photos of his data.

“I was hooked,” Wyman says.

His first published photograph, of mating scissor-tailed flycatchers, graced the back cover of Texas Ornithological Bulletin in 1976. In 1979, National Wildlife featured a full-page photo of a roadrunner bringing a Texas collared lizard to its young.

In a single month, March 1982, Sports Afield, Petersen’s Hunting, and American Hunter ran Meinzer cover shots. His nascent photographic skills were quickly catching up with his talents as a student of the land.

In South Texas on one of the East Ranches, I watched Wyman grunt, paw the dirt, and clack his rattling horns for a few seconds. Then he paused.

“Here comes one,” Sylinda whispered.

The biggest white-tailed buck I’ve ever seen was running straight at us. Then another impressive buck trotted into view. The big boy smelled a rival, swaggered in, and gave us a nice broadside look.

I watched Wyman rattle up dozens of bucks that week. When a spot had been rattled out – the bucks wised up or wandered off in search of hot does – Wyman’s handmade calls would bring in coyotes.

In one instance, a South Texas bird of prey known as the caracara was charmed. Once, a bobcat, fooled by Wyman’s dying rabbit call, jumped on his back. Another time, some curious javelinas showed up.

Yes, Wyman was calling during the peak of the whitetail rut in some of the best wildlife habitat in the Wild Horse Desert. But to consistently lure Boone and Crockett bucks is a feat. So too is fooling a coyote –one of the world’s wariest and most adaptable predators. Calling of this caliber – to within ear-scratching range – requires skills that largely disappeared with the passing of the American frontier. To routinely do so, in a wide range of habitat – from the badlands of the Rolling Plains, to the sandhills of the Texas Panhandle, to the brushland of South Texas – requires a combination of native talent, decades of experience, and a naturalist’s soul.

Evidence of this came via Geococcyx californianus, the greater roadrunner. Wyman literally lived with roadrunners, capturing the birds’ lives in some of the most arresting wildlife photos ever taken.

“I found six pairs that would actually accept me as a friend and let me go on hunts with them. For weeks during nesting season, I would hunt with these birds and get up near their nests and give them grasshoppers. I could even reach in and pick up one female out of the nest. I basically became a six-foot tall roadrunner,” he says.

A friend suggested Wyman develop a book proposal featuring roadrunners. He did so, and The Roadrunner was published in 1993 to wide acclaim from wildlife biologists and fellow photographers. Texas Tech University Press has never let it go out of print.

By the time I arrived in Benjamin at what I now refer to as the Meinzer Compound to meet with Wyman on the Four Sixes project, he had already been dubbed the State Photographer of Texas by Gov. George W. Bush. His CV included hundreds of cover shots and thousands of photo credits.

Judith, our wise editor, had encouraged each of us to develop our individual visions of the Four Sixes. Then she and her editorial and design teams would weave together Wyman’s photography and my essay. Even though we were several months into the project, our paths crossed on the Sixes only once.

For the life of me, I can’t remember why we thought a meeting necessary, but meet we did. Sylinda invited me in and said she’d have to find Wyman.

Directly, I heard, “Wyman, get these traps out of the middle of my floor and go put them in the jail!”

As I soon learned, one of the key features of the Meinzer Compound was the original Knox County Jail, which dates back to 1887. Wyman bought it decades ago. Nowadays, he stores everything from old photos to unruly guests out back.

He and I spent the next few hours talking about guns, traps, buffalo hunters, and the 1841 Texas—Santa Fe Expedition. Soon it was time to run to Knox City for lunch. That afternoon, about an hour before I needed to get back on the road to Dallas, Wyman began our “meeting” by tossing two slides on his light table.

“Which one you like best?” he asked.

Both were gorgeous shots of cottonwoods along Dixon Creek. Not wanting to seem dense, I picked one.

Wyman said, “All right then.”

He nearly sent me into cardiac arrest when he ran his thumb through the other slide and tossed it into the trash can. We went through another dozen or so selections, each ending in the destruction of a slide I’d have been insufferably proud to have claimed as my own.

In an instant, our conversation turned to rifle sights, and our project’s only scheduled meeting concluded. Last I heard, 6666: Portrait of a Texas Ranch is Texas Tech University Press’s all-time bestseller.

Chafing at the financial limitations and artistic constraints in traditional publishing, the Meinzers founded their own publishing company, Badlands Design and Production, in 2007. One of Badlands’ first books, Working Dogs of Texas, had Wyman and me hanging out with coonhounds, prison dogs, bomb sniffers, police dogs – nearly every imaginable type of canine with a job. On a bitter-cold, drizzly night in East Texas, Wyman lay on the wet ground for half an hour, shooting up at three coonhounds hammering on a huge loblolly pine that held an inconvenienced boar coon. While Big Wayne McCray tried to keep his headlamp trained on the action, our host, Donny Lynch, said, “I swear, old Wyman is working his ass off.”

The images just go on: Wyman atop a twenty-foot step ladder, shooting down at a snapping, snarling, leaping police dog; an airport beagle busting half a dozen Lufthansa passengers carrying banned fruit and meat in purses and backpacks; the two of us sloshing along a muddy ranch road after a day of hog hunting with blackmouth curs, Catahoulas, and pit bulls. Then we hear Sylinda’s voice come in over the speaker: “Where are you, boys? It’s wine time!”

On a sweltering August afternoon in 2009, I arrived at the Compound and found two wolf pups cooling themselves in a water pan. A few days prior, a man had shown up with the wolf-husky hybrids and said if Wyman didn’t take them, they’d be put down.

“Wyman, what in the world are you going to do with these wolf pups?” I asked.

He shrugged. “Just love ‘em, I guess.”

We were about to start a book about the 535,000-acre Waggoner Ranch. Wyman had already been shooting the ranch for several months, and offered to spend a couple days showing me around. First things first though. The fire pit was almost ready for steaks.

Around midnight, a few glasses of merlot to the good, I asked what time I should be up the next morning. Wyman said we’d sleep in and maybe head out a little later.

Late morning arrived at 4:30 a.m. with Wyman banging on my bedroom door. A big front was approaching, and he needed cloud shots. If we hurried, we’d be on the Waggoner just in time. Several miles north on Highway 6, Wyman was watching the road and the approaching cloud bank. Meanwhile, I wondered if we had time for me to puke in the bar ditch or if I should hang my head out the window. Just shy of the ranch boundary, Wyman pulled a U-turn that included a good portion of the southbound shoulder.

“Hell with it,” he said. “It ain’t gonna make. Let’s go get some breakfast.”

In November, at Cedar Top, one of the most storied cattle camps in cowboy lore, Wyman photographed the Waggoner wagon crew. Toward dusk, as the rich autumn light began to die out, it was easy to ignore the pickup trucks and the horse trailers parked beyond the chuck wagon and imagine the canvas teepees, wagon tent, and cook fire comforting cowboys coming in off the open range. Next morning, as the younger cowboys in Jimbo Glover’s crew jingled horses, we stood atop a trailer and watched the remuda approaching through the fog – Wyman with his camera mounted on a tripod, and me scribbling away with my pen and notebook. We talked little that morning, but both of us sensed we were capturing something important, something timeless.

“Even though the Waggoner Ranch is only a few miles from where I’ve lived my entire life, it was always a closed world, its own little country, a mystery,” Wyman says. “Very few people set foot on the place, let alone spent months exploring it. I never dreamed I would have the opportunity.”

I still can’t look at the cover of Under One Fence: The Waggoner Ranch Legacy without a touch of wonder.

A few years later, we did Wagonhound: Spirit of Wyoming without crossing paths. The 200,000-acre Wagonhound Ranch lies in Southeastern Wyoming, along the Medicine Bow Range, in some of the prettiest country I’ve seen: high, boulder-strewn meadows surrounded by aspens, craggy granite peaks, bottomland hay meadows, shortgrass rangeland rising up to the foothills, all nourished by the clear, cold tributaries of La Bonte and Wagonhound Creeks.

The book officially came out at the Wagonhound’s inaugural horse sale in September 2013. I met Wyman and Sylinda at the airport in Denver. We flew to Casper, rented an SUV, and drove to the ranch.

Wyman went on about how he couldn’t wait to spend a few days without having to worry about photography. He’d left his tripods and big lenses at home. Of course, he’d brought a camera and a couple of lenses on the off chance he’d want to shoot a photo.

When we pulled up to our cabin at Saddleback Reservoir, Wyman said, “Will you look at the stars reflecting on that water.” Before we could unload groceries, he was lying on the riprap dam. Sylinda and I stumbled about trying to steady his lens with an old saddle frame and a sofa cushion. He got his shot.

Next morning at sunup, I woke to the sound of something large walking on the cabin roof. I considered downing a handful of maximum-strength extended-release something or the other and going back to sleep, but couldn’t resist an opportunity to glimpse a Sasquatch or a bear. Sylinda greeted me at the coffeemaker.

“Wyman just couldn’t resist that view and this light.”

Of course, climbing onto cabin roofs and crawling on riprap comes with a price. Every night before bedtime, the cabin smelled of the horse liniment Wyman worked into his sore knee.

Our current collaboration will be our best yet: a photo study of a giant ranch in South Texas, one even more mysterious and closed than the Waggoner.

Blackbrush and mesquite hide stone ruins dating back to the Spanish colonial era. Troneras – gun ports cut into the thick caliche walls – speak of the Lipan Apache, bandits, and the old Comanche Trace crossing the Rio Grande above Laredo. I’ve watched Wyman crawl around fallen timbers and rusted, hand-forged square nails, mindful of rattlesnakes, determined to exploit the best light and angles.

Ubiquitous caracaras and other birds of prey hunt rich, mixed brush and savannah stretching to the horizons. During the rut, muy grande bucks come to skillful rattling. Wary old Santa Gertrudis bulls disappear into the scrub. Spring 2015 brought record rainfall and a display of wildflowers that neither Wyman nor I will ever see again.

A few more South Texas images: Wyman running through fog and wet, waist-high grass to photograph two nice bucks in a desperate fight. You could hear their grunts and ragged breathing from 80 yards away. A reeking, hissing baby vulture in an old barn, doing its best to dissuade the photographer. It failed. A coyote pup scolding Sylinda from the brush a few yards off the back porch of the lodge. Three diamondback rattlers as thick as my arm. I could go on – and do, in our upcoming book.

Looking back, Wyman says, “I’ve tried to preserve this untapped country in my images. The Waggoner, the Sixes, the Mesa Vista, the Wagonhound, our South Texas work – I hope I’ve left a footprint, a legacy that will be a source of pride for Sylinda, my boys, and our grandchildren. Every morning when I wake up, my goal is to get the best image of my life.”

His hunting drive has ebbed in recent years. I suspect that Sam and Sue, his beloved wolfdogs, have played a part. “I walk with a softer heart now. I used to hunt all the time. That’s all I could think of. I still appreciate it, and I want future generations to appreciate hunting and their Second Amendment rights. But it’s not about killing. It’s about being on the range and appreciating the life ways of the creatures. At this point in my life, it’s about being outside, seeing the sunrise, seeing the animals.”