The American Landowner: Jimmy John Liautaud

The American Landowner: Jimmy John Liautaud

LR JJ Recent Feature

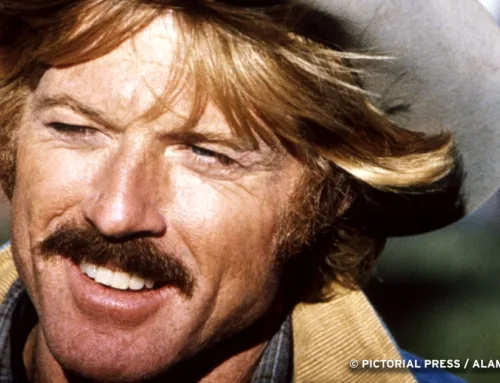

AT EASE After decades in the fast lane, Liautaud is thriving at a more relaxed pace.

Between his famous sandwiches and his colorful persona, you probably think you know Jimmy John. Maybe you’ve chomped one of the meaty creations that his eponymous empire has hand-sliced and delivered – “freaky fast” – to dorms, job sites, and dinner tables for 30-plus years. If not, surely you’ve seen the company’s breezy TV ads or passed by some of the 2,800 Jimmy John’s around the country.

Perhaps you’re even familiar with the sandwich king’s snappy banter, brash style, bold life, and big laugh.

But be careful to not confuse the brand with the man; the public face with the thoughtful, strategic entrepreneur who drove every decision at Jimmy John’s before he merged his final stake in the company into Inspire Brands a few years ago. Forbes estimates his worth at $1.7 billion.

“Jimmy John is a character. I’m Jimmy Liautaud,” he told podcaster Theo Von in 2020. “I’m really Jimmy … it’s easy for me to separate.”

No doubt, Liautaud (pronounced LEE-ah-toe) is a force of nature who flashes a large grin and a regular-dude charm. He’s a throwback to the days of sweat, hustle, and unfiltered honesty. In 1983, the 19-year-old opened his first sandwich shop in a decrepit garage in a small Illinois college town. He pulled grueling shifts — think 8:00 a.m. to 2:00 a.m. — and did the dirty work — like cleaning toilets — while painstakingly building a national chain over the course of 35 years.

He’s long been the antithesis of a scripted CEO, often wearing flannel and jeans during interviews while seasoning his candid exchanges with, “Yeah, baby!” or four-letter repartee. On a business conference stage, he may drop a cheeky observation about Millennials.

He’s joked more than once about being “the first guy to ever get canceled.” He’s proclaimed: “I can tell it like it is. I don’t care.”

That bold transparency and good-natured swagger can captivate an audience. But give a longer listen to his conversations and you’ll hear a more revealing version of Liautaud – the deliberative, precise, fiscally conservative version. He can explain the fine points of franchise financing or the ecosystems of African savannas or the recipe for a great potato chip. He’s comfortable in the minutiae.

“I’m a micro guy,” he readily admitted to Franchise Times.

Every business decision he makes is calculated to a fraction of a penny. That’s a practice Liautaud adopted at Jimmy John’s to ensure he could repeat the same cost-effective procedures thousands of times across thousands of shops. Now, he is applying his prudent ways to farmland investments.

Liautaud owns more than 7,000 acres in Illinois, as well as additional acreage in Kansas and Wisconsin. Much of his land is in Central Illinois, some not far from Champaign, original home of Jimmy John’s corporate office and the city where Liautaud lived for years in a house overlooking the Champaign Country Club. Today, he divides his time between Nashville and Key Largo.

Liautaud farms corn and beans. He also grows wine grapes. And occasionally, he ventures onto his land to hunt – a passion Liautaud picked up decades ago during an Alaskan trip taken to clear his head after a divorce. Primarily a deer hunter, he has completed extensive prairie restoration to create excellent habitat for native pheasant and quail. But his hard focus is on Class A farmland and the prime soils that Illinois offers from Champaign to Springfield to Peoria.

Liautaud chose to dedicate some of his time and resources to farmland because he sees it as a safe investment that provides “a certain amount of return,” he told Crain’s Chicago Business. “It also had to provide a recreational hunting activity for myself and my family and the people I work with who enjoy hunting,” he said.

A bit of his farmland savvy can be traced to his tenure at Jimmy John’s. Every Wednesday, in the test kitchen at corporate headquarters, he sampled sandwiches and meats, cookies, and potato chips … even the condiments.

He learned everything about every ingredient, such as how soybeans become soybean oil and, ultimately, mayo. He developed the ability to detect if any recipe element was missing or if a supplier had manipulated its product, colleagues say.

All those tastings and all that test food produced the menu. But Liautaud purposely kept that menu simple – one cheese, two bread doughs, five meats – to keep the customer experience consistent and to reduce costs across the company’s massive supply chain.

Along the way, he gained deeper understanding of agriculture and futures contracts, of cattle, turkeys, and hogs. And he then began applying those insights to the corn and beans he raised in Illinois. He fell in love with the ag game and with farmland.

“We’re very active farmers here, and we’re very actively acquiring more farms [in Illinois],” Liautaud told Champaign’s newspaper, The News-Gazette.

But he first became enticed by farmland investments two decades ago when Clint Atkins – a developer in Champaign and a personal friend – described the fairness of the farmers he encountered during many of his land dealings.

“Every time I work with a farmer, I like it because I can shake his hand and we know we’ve got a deal,” Atkins told Liautaud back then.

Atkins also shared bits of wisdom, such as what makes good soils and where those soils produce healthy crops in Illinois. Clint Atkins died in 2011. His son, Spencer, has remained friends with Liautaud for more than 20 years. Spencer knows the man well. He’s not surprised by Liautaud’s steady rise in business.

“Jimmy’s hard to miss,” says Atkins, CEO of The Atkins Group, a real estate development firm based in Urbana, Illinois. “He’s got a lot of personality and a sharp wit. He can really control a room. He’s got a huge, giving heart, but he doesn’t put up with mediocrity.”

In business, Liautaud can be a taskmaster, but he never forgets he’s working with other people, and he likes to know what’s truly important to those people, Atkins says. Liautaud carries enormous empathy and an innate capacity to understand human nature.

EYE ON THE PRIZE Behind the fun facade, it’s always been about the bottom line for this self-made entrepreneur.

“To make people make a sandwich exactly the same way every single time – and put the love into that sandwich that they do – is extremely difficult,” Spencer Atkins says.

“Jimmy has the ability to get you to drink what we call ‘the Jimmy Juice,’ what we used to call ‘drinking the Kool-Aid,’” he adds. “He can tell you his vision, get you to buy in on that vision, and follow him on that vision. His team will do anything for him.”

As rags-to-riches stories go, Liautaud’s journey from ambitious teen to the Jimmy John to billionaire farmer is certainly unique. He enjoys sharing that vibrant tale during interviews.

The true crossroads of his life came after he finished high school in 1983 in Cary, Illinois. He graduated second to last in his class. College was out of reach.

His father, James, made him a deal. He offered Jimmy a $25,000 loan to start his own business. There was one catch: If Jimmy’s new enterprise was not profitable after one year, he would have to join the Army. Jimmy accepted the deal and the loan.

That summer, Liautaud researched sandwich shops, partly because he knew the loan would cover his two big investments: a refrigerator and a meat slicer. He learned bread baking and the art of the sandwich. He chose to launch his first Jimmy John’s in Charleston, home of Eastern Illinois University, where a few of his relatives were enrolled. He opened in a former garage near the bars where EIU students hit the town. His very first menu offered four sandwiches, each priced at two bucks, and 25¢ Cokes.

The little sandwich shop was a hit. Liautaud didn’t get much sleep, but that first year, he earned a profit of $40,000 on sales of $154,000. And that was just the start. Revenues kept rising, and the next year, he paid back his dad’s loan plus interest. By 1987, he opened two more shops in the college towns of Champaign and Macomb, Illinois.

In 1993, Liautaud made a strategic shift and started selling Jimmy John’s franchises. In that same year, he made his first million. Business success, he learned, followed a time-tested recipe: Keep costs down through a streamlined menu and never take on debt. That mindset was forged via some hard-earned wisdom from childhood.

FATHER AND SON James and Jimmy John in 2010.

His father, James, was a Korean War veteran, a door-to-door encyclopedia salesman, and an engineer who pioneered a manufacturing technique called composite molding. James Liautaud later co-owned a plastics and electronics company based in Illinois. But he was forced to declare bankruptcy twice: when Jimmy was 8 and again when he was 12. To make ends meet, the family drank powdered milk, something Jimmy mentions to this day. James Liautaud passed away in 2015.

“Those bankruptcies scared me,” Jimmy readily admits. “I was poor, and I didn’t ever want to be poor again. So I was a real saver and still am. I’m very conservative. I only invest in things that I totally understand.”

That business blueprint, which would ultimately lead him to invest in farmland, helped fuel Liautaud’s sandwich company. As Jimmy John’s franchises sprouted up nationwide, the founder studied potential new locations, picked the best real estate for new shops, and figured out how many stores each market could sustain – all before modern software simplified those tasks.

He not only systemized each department, but he fostered a culture that focused on serving customers as well as franchisees. Speed, convenience, and service were always front of mind. By 2010, he opened his 1,000th franchise. Liautaud’s employees celebrated by giving the boss a giant bottle of superb wine. Liautaud was grateful, but he told them he wanted to save that big bottle for the day they hit 2,000 stores. The company reached that number in 2014, yet the bottle remains unopened.

IN THE BEGINNING The very first Jimmy John’s in Charleston, Illinois.

Liautaud prefers to think about what’s next, not about the milestones that mark past achievements.

Not long after Jimmy John’s opened its 2,000th store, Liautaud sold an estimated one-third stake in his company to Atlanta-based private equity firm Roark Capital. That 2016 deal was valued at $3 billion, according to Forbes. In 2019, he merged his remaining stake into Inspire Brands, an arm of Roark Capital.

“I got out of the day to day completely,” he said.

During that same span, he began investing in farmland, an asset he financially understands and personally enjoys. To Liautaud, his dirt feels like a secure haven for the money he toiled to earn and save. “I love the way it smells. I love that it never shows up late or calls in sick,” he says.

This mindset ties directly to another aspect of his money-management philosophy: “Money is hard to make and five times harder to hold on to.”

Nowadays, when he’s not at home in Tennessee or Florida, Liautaud can often be found on one of his farmland properties either discussing his crops or traversing acres of well-tended habitat that nurtures the plentiful deer, turkey, and pheasant.

At 58, his personality remains powerful, but he’s definitely found tranquility. “My resting heart rate when I wake up in the morning now is under 60. It was like 100,” he said recently. “The noise is gone, and the peace is here.”

All photography courtesy of Jimmy John Liautaud.