Garst Farms: A Legacy of Innovation

Garst Farms: A Legacy of Innovation

By Bill Briggs

Garst Farms Aerial

The terraces, contour grass strips, and waterways put in place by the Garst family will be preserved in perpetuity.

It’s an idyllic swath of Western Iowa, a patchwork of lush farmland, hillside terraces, grassed waterways, and trees favored by Monarch butterflies. Here, a maverick seed salesman once fed the roots of modern American farming, then fed lunch to visiting Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. And here, the first sprouts of a new ag revolution may offer a hopeful blueprint to save the tired soil – and perhaps even the planet. A touch dramatic? A bit overblown? Well, withhold that judgment for a quick second and take a close look at the recent sale of those same acres.

At a live auction on August 17 at the Raccoon River Social Club, local farmers bid against one another as they vied for eight tracts of Garst family farmland totaling 1,998 acres outside Coon Rapids, a small town where the Garsts have been raising corn and soybeans for nearly a century. Altogether, the parcels fetched $19.3 million, or $11,461 per tillable acre.

The Des Moines Register described the final sales totals as “hefty.” The listing agent called it “exceptional.” The Garsts said simply: “We’re grateful.”

QUOTABLE“Buy land. They’re not making it anymore.”-Mark Twain

But here’s the catch: Despite a scorching hot market for farmland across the Midwest, nobody knew how the sale of those prized plots would go.

“Going into the sale, that was the million-dollar question,” says Steve Bruere, president of Peoples Company, which marketed and auctioned the farms in conjunction with Community Insurance Agency of Coon Rapids.

First-of-a-Kind Soil Conservation Easement

That’s because all 1,998 acres that belonged to the Garsts were protected by a soil conservation easement, a first-of-its-kind stipulation that permanently governs how that land must be farmed – and how it cannot.

In short, existing terraces, headlands, waterways, and riparian buffers must stay as-is, tillage is prohibited, and roots must continually remain in the ground. Those measures, installed years ago on the Garst family land, fortify the nutrient-rich topsoil, and prevent the kind of erosion that conventional farming practices have inflicted across the Heartland.

The Corn Belt alone has lost one-third of its topsoil due to erosion, harming water quality, stripping carbon from the fields, slashing corn and soybean yields by 6 percent, and cutting farmers’ profits by $3 billion a year, according to a new study recently released by the National Academy of Sciences.

“In my book, soil erosion is everything because you can’t come back from that,” says Liz Garst, the family’s business manager. “It took 10,000 years to build the topsoil we used to have. Once it’s gone, in any meaningful sense, it’s gone.

“We decided, with the sale of this land, we wanted to make sure our work is protected, and we wanted to send a message to Iowa farmers that they can do better,” Garst adds.

Five nearby farmers bought into that message by buying the tracts, Bruere says. He estimates that even with the restrictions attached, the parcels sold at a mere 10 to 15 percent market discount.

One of those farmers, Karl Eischeid, bought a 240-acre tract, paying $11,000 per acre. Since the early 1990s, he’s owned farmland adjacent to that tract, which is sharecropped by a farm operator and his two sons. Eischeid was drawn to the parcel’s proximity, the soil’s high productivity score — it earned a Corn Suitability Rating of 88 out of 100 — and to the Garsts’ long view for safeguarding the land.

“The Garst family took a chance on putting the easement practices in place, knowing that this could lower the value of the auction,” Eischeid says. “However, they placed a higher value on their perception of conservation and what we leave behind for our future generations.”

Here’s the thing, though: The Garsts aren’t simply compelling the new owners to do right by the land. The family knows that true stewardship brings better agricultural output. Their yield increases have consistently beaten county averages. Protecting the soil has been profitable.

Liz Garst, herself a plainspoken farmer with Harvard and Stanford degrees, is quite sure the easement offered buyers a clear model to reap that same success.

“We’re not just altruistic,” she says. “A smart way to make money is to take care of soil.”

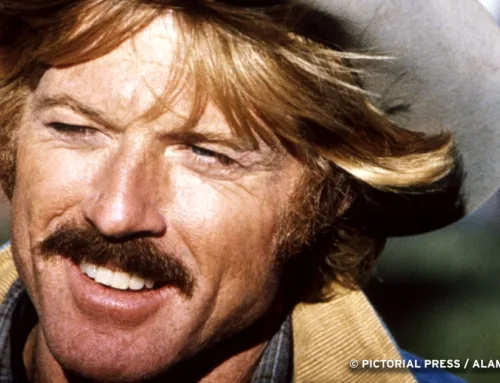

Yes, the conservationists are most definitely capitalists. They’ve been that way since the day Garst invited the Khrushchevs to travel from Moscow to Coon Rapids to enjoy a farm lunch of fried chicken, stuffed tomatoes, and apple pie. And, just maybe, to buy a whole lot of his hybrid corn seed.

The Innovator

The patriarch — Roswell “Bob” Garst — was chock full of wild ideas. Wild for the times, anyway, yet notions that eventually would help transform how America farms.

Before all that, Garst was selling real estate in Des Moines when the Great Depression leveled the country in 1929. He quickly teamed up with Henry Wallace, a fellow big-thinking businessman from Iowa.

For several years, Wallace had been producing and selling a high-yielding hybrid corn seed he named Copper Cross. Wallace, who later would become President Franklin Roosevelt’s secretary of agriculture and his second vice president, had learned the science of hybrids from George Washington Carver.

As the Depression deepened, Garst returned to his hometown of Coon Rapids and began selling Wallace’s hybrid seeds throughout Western Iowa. In 1931, he cofounded his own venture, the Garst and Thomas Hybrid Seed Corn Company.

“Hybrids were the magic change agents,” his granddaughter Liz Garst says. “Before then, you saved your own seeds, the only fertilizer was manure from your own farm animals, and the only power came from your own draft animals.”

Hybrid corn grows faster, is more disease resistant, and produces higher yields. In 1933, just 1 percent of Iowa farmland was planted with hybrid seed. By 1943, almost all the fields were hybrid. Roswell Garst had helped spread the gospel of hybrids to farmers across the Midwest. He also got rich selling his seeds.

He began buying dying farms and reviving them by restoring the soil. He graded the ditches, seeded the waterways, and converted some land back to pasture. He raised calves and cows by feeding them corn cobs and stalks. He championed nitrogen fertilizer and mechanization to plant and harvest his crops. His conservation boosted the yields — and it ultimately became a family religion.

When Roswell’s son Stephen later farmed the family’s land outside of Coon Rapids, he continued using terraces, seeded waterways and headlands, and he became an early adopter of no-till practices. He refused to break up the soil in spring and fall, blocking erosion and building organic matter in the ground.

The First Secretary

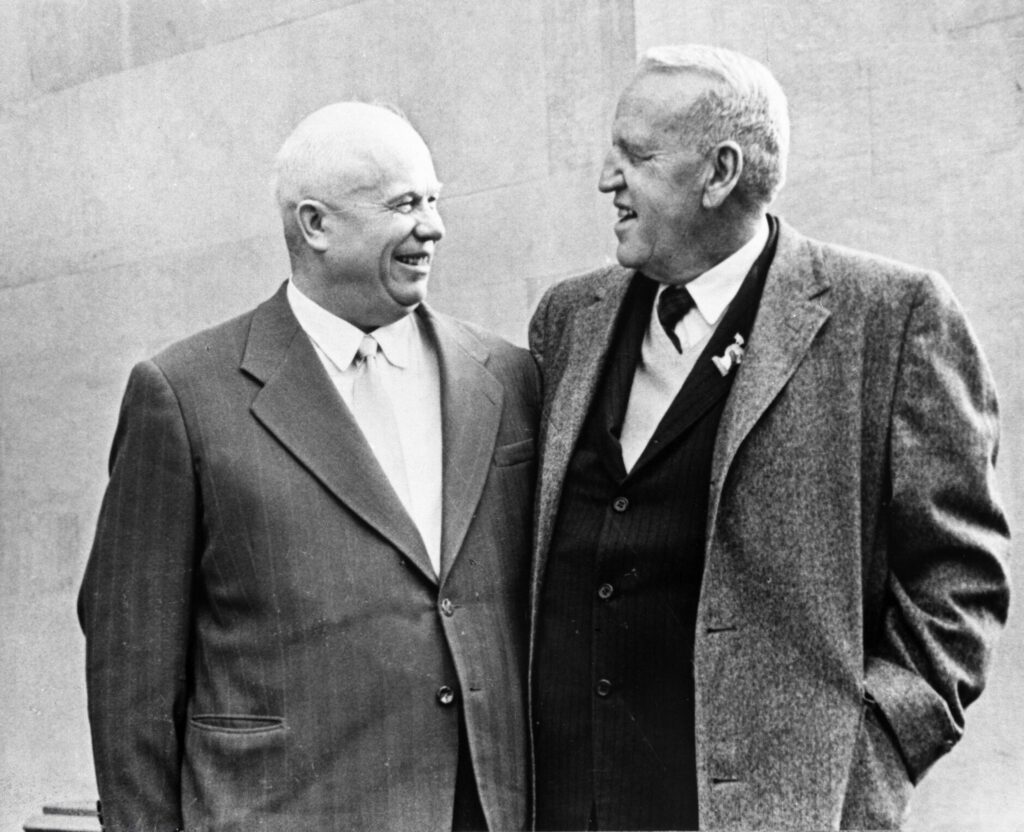

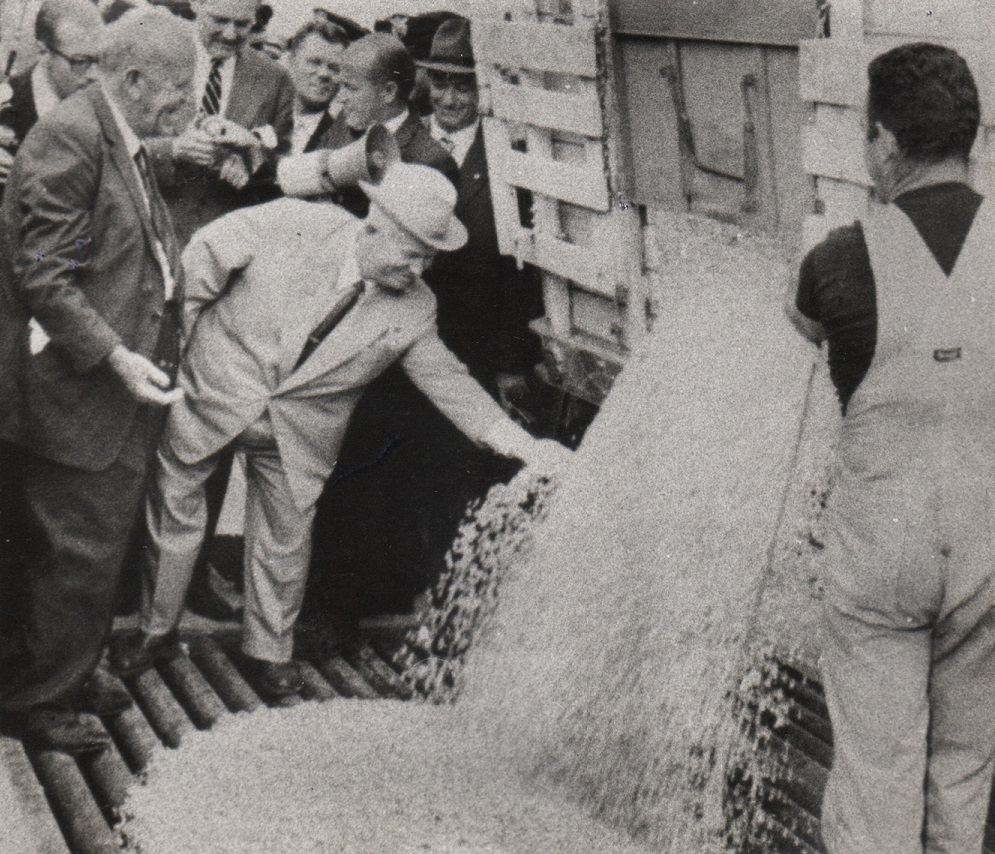

By the mid-1950s, Roswell Garst was still hawking corn seed, and he had his eyes on a potential new market, the Soviet Union. At the same time, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev was gazing longingly at Iowa, proclaiming that the fatherland needed its own version of the Iowa Corn Belt. Khrushchev was desperate for a homegrown bounty of meat, milk, and eggs for his people.

The editor of the Des Moines Register read that comment and published a letter to Khrushchev, inviting him to Iowa to learn how they grew food in the Hawkeye State. In 1959, the Soviet premier arrived for a US tour. Along the way, he ventured with his wife to Roswell Garst’s farmhouse, followed by a gaggle of journalists.

Roswell had two motives for the visit. First, to make money. Second, to throw a small amount of deicer on Cold War tensions by helping Khrushchev feed his nation. Roswell believed that hungry people were dangerous people, and that the Soviets wouldn’t be good global neighbors until their bellies were full.

“I think from our own selfish interests,” Roswell Garst subsequently wrote, “we cannot afford to have one-third of the world possess the atomic bomb and the hydrogen bomb and nothing else — and to be hungry at the same time. That’s too great a temptation.”

Under a circus tent in the backyard, the men feasted on fried chicken. In the nearby corn rows, they talked farming. The two realized they had much in common. They each saw themselves as peasants. They each appreciated fertile soil. They liked each other.

Liz Garst, then 8, still speaks fondly of that unlikely bond and the warmth of the moment. “I remember sitting on Mrs. Khrushchev’s lap and liking her. She smelled good and didn’t hold me too tight. It was a great day,” she recalls.

Seed Sales

And in the end, her grandfather did sell the Soviet leader some of his seed corn.

In 2004, when Liz’s father died, Liz took over the family’s farmland. Soon, the family sold or gave away thousands of acres of their land near Coon Rapids.

Some of it — including Roswell’s old farm — remains a preserved stretch of pasture, prairies, timber, and oak savannas in the Middle Raccoon River Valley. Those 4,200 acres were donated to Whiterock Conservancy, a nonprofit land trust created by the Garsts and controlled by a board of directors.

Appraised at more than $13 million when gifted, that bequest represents one of the largest land gifts in Iowa history. To this day, a portion of those acres continues to be farmed using no-till practices and cover crops.

“It is,” Liz Garst says, “simply beautiful.”

But, she adds, other acres sold that year by the family didn’t fare as well.

On those parcels, pasturelands were ripped up and turned into traditionally tilled row crops. Waterways and terraces were torn out.

The ensuing disappointment became the major impetus for attaching the soil conservation easement to the tracts sold on August 17. Whiterock Conservancy will enforce the easement rules in perpetuity, sending out a representative at least twice a year to monitor compliance.

“In the past, it was hard to see our beloved land abused,” Liz Garst says. “We’ve invested a lot in protecting these farms and making them better. On the other hand, we’re requiring things that will make any landowner more money.”

Why sell the tracts now? As Liz Garst explains, she just turned 70, and no other family members are ready to take the business reins. She also foresees electric cars and artificial meats cutting into the market value of farm acres.

But her deep affection for the land continues to fuel who she is. The oldest of six siblings, she was especially close to her farmer father. She began working the same soil at age 8, herding cattle on horseback, mowing the fields, and rogueing the corn. She has explored many more of the place’s nooks during hikes, hunts, and family picnics. The Garsts still own 1,200 acres. (Liz farms 80 of those.) Eventually, all will be gifted to Whiterock.