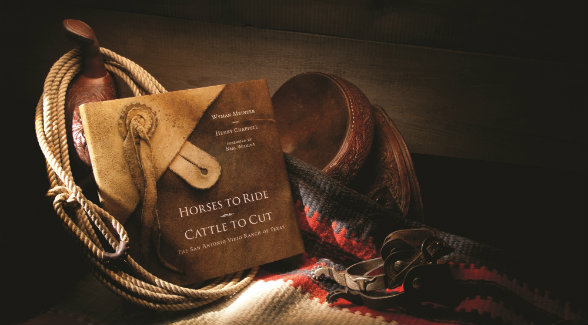

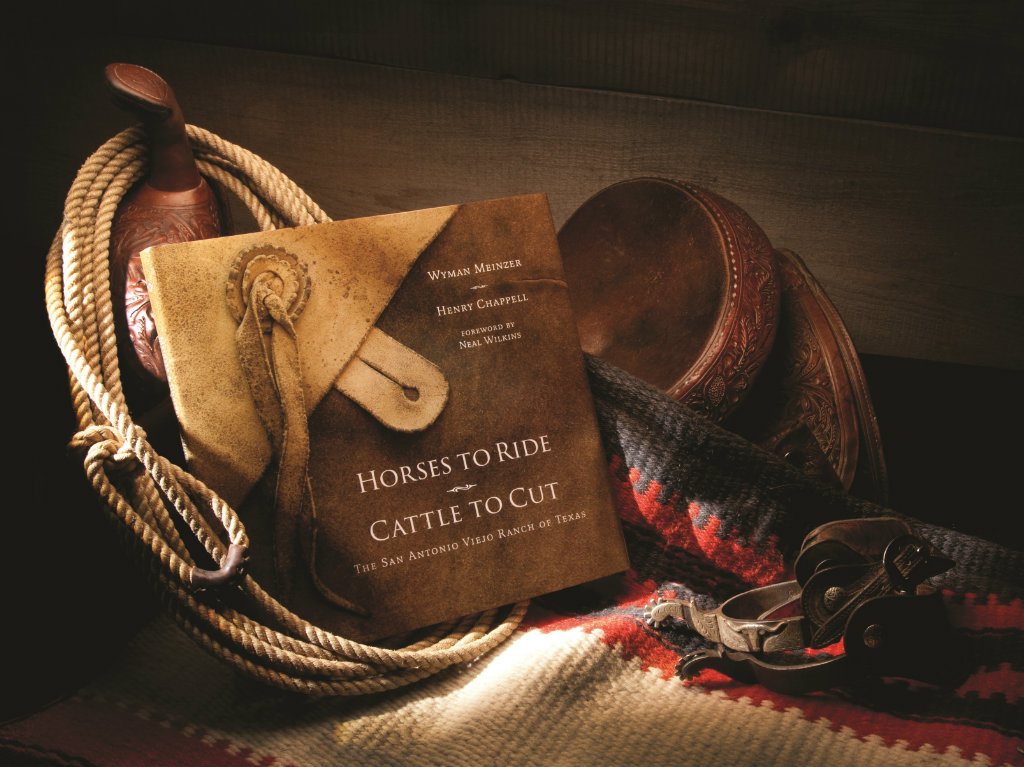

Horses to Ride, Cattle to Cut

Horses to Ride, Cattle to Cut

Horses01_fi

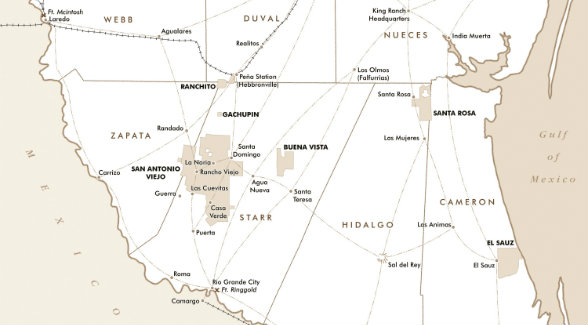

The San Antonio Viejo Ranch of Texas

| Original Photography by Wyman Meinzer

Given rain, the Wild Horse Desert will heal after drought and hard use by humans and livestock have left it battered and bare. Within days, beaten ground will be hidden under midgrass and scores of species of flowers and less showy annuals, though the mix may suggest recent history – a water lot full of waist-high sunflowers; a carpet of ragweed and croton beneath a giant mesquite; a line of prickly poppy and Texas thistle that from a distance suggests a ranch road or two-track through the grass and scrub.

While grass and annual cover hint at recent history, a few woodland patches hide a much older story. In southern Jim Hogg County, some five miles east of Guerra, you can pass unaware within yards of two-story stone ruins. If you’re persistent and alert, you might glimpse pale stone through the brush, and then walls looming overhead, and finally the roofless structure.

Magnificent mesquite savannah like the landscape that once lured Richard King, Mifflin Kenedy, and the East family to the region exemplifies the best grazing land in South Texas.

Mindful of rattlesnakes, hidden wells, and Africanized honey bees, you pick your way through the brush, perhaps climbing over piles of stone, and peer through a window or door framed in mesquite timber as sound as the day it was cut. Solid beams that once supported a roof of chipichil – mortar made of lime, sand, and gravel – lie amid piles of rubble and rusty square nails, forged one at a time by a blacksmith gone two centuries now. Brush grows through cracks in the floor, through windows. China shards and a fireplace filled by a rat midden conjure images of a home graced with furniture from Laredo or Matamoros. Walls of sillar blocks quarried from local caliche deposits and hauled by donkey or ox cart, some surely weighing a hundred pounds, remain stacked two stories and two feet thick and chinked here and there with smaller stones, square and sharp as any product of a modern quarry. Inside those thick walls, families woke cool on summer mornings. A single room wide, with windows on both sides, built to take advantage of prevailing breezes, the house would’ve been tolerably cool on all but the stillest summer days.

Peculiar triangular apertures in walls, large as a dinner plate on the inside, tapering to an outside exit no larger than a man’s fist – troneras, gun ports – remind us that the east fork of the Comanche Trace crossed the Rio Grande only 180 miles upriver from Laredo and that raiders from the Texas Panhandle and the Arkansas River who plundered as far south as Monterrey would think nothing of a two-hundred-mile excursion for a chance at scalps, loot, cattle, and Tejano women. Nor did the Comanches’ old enemy, the Lipan Apaches, driven from their ancestral home on the Southern Plains in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, welcome newcomers to their adopted home.

From inside the house, two practiced shooters, protected by the thick stone walls, could lay down terrible crossfire with flintlock muskets or, a century on, breech-loading rifles. At the same time, tall, narrow, similarly tapered windows allowed for protected shooting.

Hand-dug wells, some 60 feet deep and lined with sillar, and nowadays often occupied by Africanized bees, testify to a people who knew how to live in droughty country. Old deeds and records of land grants and adjudication, local history, and a few grave markers provide only sparse, bold lines in the palimpsest. We know remarkably little about the few score or few hundred people who formed a community here.

The threat of drought has haunted South Texas cattlemen since the first Tejanos built jacales and dug wells in eighteenth-century Nuevo Santander.

Decades before Stephen F. Austin’s Old Three Hundred settled at San Felipe, stockmen from various provinces in New Spain moved north of the Rio Grande into Nuevo Santander. Unlike Puritan farmers who settled New England, Cavaliers who claimed the southeastern seaboard, or Scots-Irish yeomen who razed forests and wore out farms from the Virginia coast to the 98th meridian, these pioneers pushed into what would become South Texas armed with ranching skills and tools of a culture developed on the Iberian Peninsula during the late Middle Ages and refined to New World conditions by generations of Indian, Mestizo, mulatto, and Spanish herdsmen. Elsewhere in the Southwest, settlers followed and depended on missions and presidios. Early rancheros on the northern frontier of New Spain provided their own security and spiritual sustenance.

The earliest Tejano settlers called this place San Antonio – distinct from San Antonio de Bexar, some 200 miles north. By the 1850s, chroniclers called it San Antonio Viejo – Old San Antonio – while surveyors sometimes referred to las Norias de San Antonio, the San Antonio Wells. Sometime after 1915, those who’d left the community and those who’d simply known it began calling it Rancho Viejo.

Whatever they called their community, the people who built these stone houses came to stay, and to leave a durable home to their descendants. As had their predecessors, Coahuiltecan peoples who dominated South Texas for millennia, their subgroups thrived or subsisted from the Balcones Escarpment and Colorado River south into Nuevo León and Tamaulipas.

The harsh conditions of the South Texas plains left few possibilities for cultural development by native people. By 1528, when Coahuiltecan bands encountered Ãlvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and his three castaway companions, a way of life virtually unchanged for thousands of years had already been doomed by events in the Caribbean.

In 1494, on his second voyage to New Spain, Christopher Columbus unloaded 24 stallions, 10 mares, and a small herd of cattle on the northern coast of Hispaniola. The first small cattle ranches were founded on the island in 1498. Less than a decade on, the West Indies teemed with cattle, many of them wild.

The first cattle to reach Mexico arrived in the winter of 1521 when Gregorio de Villalobos landed at the mouth of the Pánuco River near present-day Tampico. Cattle ranching spread rapidly between Veracruz, on the coast, and Mexico City. Hernán Cortés established a ranch in the Mexicaltzingo Valley, registering one of the first brands in the New World, three Latin crosses. These were large seigneurial holdings requiring substantial labor forces, which local Indians, forced into feudal vassalage, provided.

By the 1530s, well-connected Spaniards were pushing northwest from Mexico City on grazing land granted by the Crown. Rich silver strikes in Zacatecas in 1546 and the resulting mining industry provided a profitable market for beef, tallow, and hides.

Hernán Cortés brought the horse to Mexico — and forever changed the history of the American continent. Cattle came soon after.

In The Longhorns, J. Frank Dobie wrote: “In 1540, only 19 years after the initial introduction of seed stock, Coronado, without any effort worthy of note, gathered at least 500 head of cattle, besides thousands of sheep, goats, and hogs, to supply food for his great expedition in search of the golden Seven Cities of Cibola.” Probably, these were the first cattle to enter present-day Texas.

By 1600, however, the Spanish Empire had fallen into decline. Wealthy Spaniards in the New World increased their power by purchasing full title to vast acreages from the cash-starved Crown. On the great haciendas in the northern provinces of Durango, Nuevo León, Coahuila, and Chihuahua, hacendados (ranch owners) ruled like feudal lords over everything within their property boundaries.

As ranching expanded northward toward Texas, so too did presidios – military outposts established for protection of settlements – and Franciscan missions charged with Christianization and agricultural training of natives. Yet, on the northern edge of the frontier, haciendas provided their own protection in the form of watch towers, battlements, and troneras. Well-armed vaqueros could be mustered into effective defensive forces.

In the meantime, the Coahuiltecans were being ravaged by smallpox and other contagions to which they had no resistance.

By 1749, when José de Escandón arrived in the Spanish province of Nuevo Santander with 3,000 settlers and 1,460 soldiers, the indios bárbaros, who’d suffered Spanish slave raids and brutal treatment as forced servants, who’d resisted settlement and denied access to ports, salt deposits, and rich grazing lands, were already in serious decline.

Escandón found a ranching frontier already in place; some of the ranchos were founded as early as 1730, when ranchers from Coahuila and Nuevo León moved into the region, establishing villas (towns), lugares (settlements), and haciendas, mostly on the south side of the Rio Grande. Escandón promptly founded two villas, Camargo and Reynosa. By 1855, there were 23 settlements along the river. By the end of the century, the province’s population would reach 30,000, far outpacing growth in Texas, even though Nuevo Santander was the last province conquered and colonized by Spain.

La BahÃa Presidio and Nuestra Señora del EspÃrtu Santo de Zúñiga Mission, then on the Guadalupe River far to the north, could provide neither protection nor spiritual sustenance. The northernmost ranchos formed the true frontier of New Spain.

Settlers on the south bank of the Rio Grande often risked Indian attack and water shortages to graze stock on the north side of the river. After 1755, villas began to form and grow along the north bank – Laredo, Roma. Outside the bounds of large haciendas, stock grazing remained largely open range.

In 1767, Spanish authorities began a survey of villas in the province, and in response to requests for individual land grants, began to divide grazing lands along the river in the vicinity of villas into elongated quadrangles called porciones. Most of these consisted of five to six thousand acres and were granted on the basis of seniority and merit. Some 170 porciones were granted along the north bank of the Rio Grande.

Santa Gertrudis crossbred as well as mixed-breed cattle typify the modern San Antonio Viejo herd today.

North of the porciones, much larger acreages were granted to prominent settlers in Mier, Camargo, and Reynosa. The grantees agreed to stock, improve, maintain, and reside on their lands. Many, however, remained absentee landowners, living in villas or on their porciones while hired vaqueros and their families occupied the remote ranchos.

Of course, many stockmen simply appropriated and occupied unclaimed lands for years or even decades, and then applied for grants and titles on the basis of long use. Such was likely the case at San Antonio Viejo.

Near the beginning of the nineteenth century, Francisco Xavier Vela, a soldier and self-described “loyal vassal,” began grazing livestock on a four-league tract some 45 miles north of present-day Rio Grande City, then part of Carnestolendas Ranch, which was established in 1762 by José Antonio de la Garza Falcón. Vela had, according to his denuncio, or claim, “settled it in times of drought, despite the dangers of barbarous Indians” and that the land in question belonged to the Spanish Crown.

Officials in Mier agreed and sent out a surveyor, José Antonio de la Garza, who found near the middle of the tract a jacal made of woven leaves of Spanish dagger and roofed with straw, and a well lined with mesquite sticks, containing water both poor in quality and insufficient in quantity for Vela’s small herds. West of the well, Vela had built a rough mesquite corral. Farther west still lay a small laguna called San Antonio, dry at the time of inspection but said to hold only meager water during periods of ample rain.

Garza considered the land of little value, perhaps 10 pesos per league, due to the likelihood of Indian attacks. On September 15, 1807, Vela’s representative, José de Herrera, a military officer, offered 15 pesos per league and another 16 pesos for administrative fees. Upon learning of the well on the tract, the intermediary’s attorney demanded 30 pesos per league. After further negotiation, officials issued the title on March 18, 1809. The formal ceremony was held on July 14, 1809.

To accept Garza’s assessment of the Vela tract is to date the stone ruins at Rancho Viejo no earlier than 1806, the year of the inspection and survey. Yet why would Vela risk Indian attack – and by 1800, not from the hunting and gathering Coahuiltecans, but the aggressive Comanche and Lipan horsemen – for grazing land with poor prospects for good wells, and a laguna that held little water even after generous rains? Perhaps Vela saw potential that he had good reason to keep from Garza, or maybe stockman and surveyor worked out a mutually beneficial arrangement. Nineteenth-century accounts often refer to the “San Antonio Wells,” and indeed, several sillar-lined wells can be found amid the ruins today. Some, despite no maintenance for a century or more, still hold water in some seasons. The tract sits on the western edge of the South Texas sand sheet where excellent water from the Gulf Coast Aquifer is readily accessible along a narrow north—south corridor, east of which the aquifer begins its coastward down-dip. It’s no coincidence that frontier-era roads and trails developed along this well-watered corridor, without which Vela’s denuncio would have been folly. Furthermore, Paraje (Station) San Antonio Viejo, the site of the later community, had been established as a Spanish army post as early as 1723, being strategically located on the road connecting Cerralvo to settlements in the north – an implausible prospect without reliable water.

Wagons like these that survive on the San Antonio Viejo today were used to haul contraband Confederate cotton bales through Rancho Viejo.

Only a year after issuance of the title, revolution broke out in Mexico; war reached the province by 1811. Whatever Vela’s allegiance – we might assume that a “loyal vassal” would remain a royalist – the revolution must have been extremely disruptive to affairs in Nuevo Santander.

Yet by 1821, and the end of the revolution, the lugar at the San Antonio Wells may have been a thriving community at the fork along Camino Real leading from the salt mines in the south, branching northwest to Randado, and northeast to San Diego and to Santo Domingo, a settlement appearing on frontier maps. As the settlement grew, establishing its businesses, stockmen likely grazed their cattle on common, unfenced pastureland, relying on the mesta – a local cattleman’s association – to enforce rules, and roundups to brand, wean, and sort. Individually these were small ranching operations – ranchos – as opposed to large seigneurial haciendas in the provinces south of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas.

In addition to comfortable stone houses owned by merchants and prosperous stockmen, humble jacales would have housed peasants. Although still socially stratified, the community would have been considerably more egalitarian than the old feudal societies still common to the south. Wage labor, rather than peonage, characterized the lot of common members of the lugar.

Early on, commerce focused southward toward the villas along the Rio Grande. As northward routes expanded and ports developed on the coast, the communities adjusted and prospered accordingly.

Comanche and Lipan attack remained a constant threat. At times, area ranchos were abandoned for the relative safety of the villas along the Rio Grande. Drought could prove nearly as disastrous as Indian raids; trade and fortunes swelled and shrank with increased and decreased rainfall.

Although the Texas Revolution of 1836 roiled Anglo settlements far to the north and east, disorder and uncertainty surely affected Trans-Nueces lugares and villas. Some of the earliest Anglo banditry occurred during and after the revolution, with brigands using retribution as an excuse for plunder.

With Santa Anna’s surrender at San Jacinto, the new Republic of Texas considered the Rio Grande the international boundary. In spite of the dictator’s concessions at the end of several hundred gun barrels, Mexico continued to claim all of South Texas between the Nueces and the Rio Grande. With virtually no Anglo-Texan settlement in the Nueces Strip, and little ability by the new republic to enforce its claim, residents and landowners in South Texas likely felt no less Mexican than before the revolution, and went about their business as usual.

At the San Antonio Viejo, fortunes waxed and waned in response to natural and outside economic forces beyond the ranch’s control. Despite increased banditry and overall violence in the Nueces Strip, the tough, resourceful Tejanos persevered, wary as always.

Prior to 1900, the area around San Antonio Viejo was the crossroads for several routes used by the military and for commerce to and from the Rio Grande.

Conditions on the South Texas frontier grew more precarious after the outbreak of war between Mexico and the United States. Now, not only did recently annexed Texas declare the Rio Grande a boundary, so did the United States.

The war years, 1846—1848, must’ve been an anxious time for rancheros in the Nueces Strip, even as the seasonal rhythms of roundups, branding, weaning, shearing of sheep, hog killing, and small-scale planting and harvest continued. A mixture of rumor and solid news, days if not weeks old, surely kept the northern frontier on edge. First came the indecisive battle of Palo Alto, and then the defeat at Veracruz, then the long, humiliating occupation of Mexico City by Winfield Scott’s forces.

Though the merchants, rancheros, and vaqueros of the community at San Antonio Viejo were no doubt stunned by the enormity of land purchased by the United States for a mere $15 million, they could not have been surprised to learn that their lugar and surrounding grazing lands now resided within the United States, for the Nueces Strip, their home territory, had been contested ground since the end of the Texas Revolution in the spring of 1836.

Yet the reality that they must become American citizens, and Texans more specifically, if not culturally, or forfeit ownership of their lands, must have been jarring. No doubt some rancheros cut their losses and crossed the Rio Grande into a territorially diminished Mexico.

Banditry, long rife in the region, reached unprecedented levels as brigands exploited the disorder and confusion in the wake of Mexico’s defeat. Anglo-Texan rustlers stole cattle on both sides of the border, while Mexican bandits stole mostly north of the Rio Grande and drove cattle into Mexico to sell. So brisk was the trade in hides, thieving Mexican bandits resurrected use of the hocking knife, outlawed three centuries prior in Mexico. The hapless cattle, tendons severed by the medieval implement, were killed and skinned where they fell, their naked carcasses left to rot.

While frontier-hardened Tejanos knew how to deal with bandits, they were far less well equipped for Anglo-Texans moving into the area to purchase land under American laws. Although the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo provided some assurance that Spanish and Mexican land grants would be honored, confusion and distrust remained, even among heirs of original grantees along the Rio Grande. Mistreatment of Tejanos loyal to the Texas Revolution, such as Juan SeguÃn, hero of the siege of the Alamo, only deepened distrust.

Certainly, some Tejanos sold out because of Indian raids and banditry; others were swindled or intimidated. Tejanos owning the most valuable land, porciones along the river, and other well-watered grazing lands, were understandably reluctant to sell. Even today, much of the land granted to the original settlers remains in the hands of their heirs while Anglos own most of the land closer to the Nueces.

To adjudicate land grant claims and restore a modicum of trust and good will, the Texas Legislature on February 5, 1850, passed an act specifying the appointment of a commission to investigate all claims to Spanish and Mexican land grants between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande.

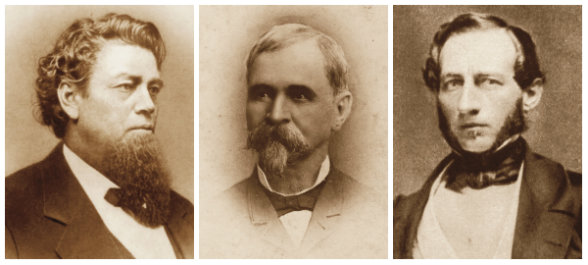

Three towering figures left an indelible mark on South Texas: King Ranch founder Captain Richard King (left); his business partner, Captain Mifflin Kenedy (center), who founded the Kenedy Ranch; and their business partner, a flinty New Englander named Charles Stillman (right). Photography courtesy of King Ranch Archives, King Ranch Inc., Kingsville, Texas.

Contrary to persistent border lore, the Bourland Commission, composed of William Bourland and James Miller, both experienced public officials, performed honorably during their two years along the border, overwhelmingly and justly favoring Tejano claimants. Furthermore, many Tejanos were reluctant to sell only because land prices remained low during the uncertainty following the war. After the Bourland-Miller rulings quieted titles, some of these rancheros sold willingly. During the decade following the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, some 80 percent of the land in the formerly contested territory changed hands.

Meanwhile, even as the community at San Antonio Viejo thrived as it remained on the main trade route through Rio Grande City into Camargo and Mier, in Mexico, it remained vulnerable to increasing Comanche raids.

Around fall of 1849, the State of Texas stationed Captain John Salmon “Rip” Ford and his company of rangers south of the Nueces to protect settlements and supply trains traveling to and from Fort Ringgold or “Ringgold Barracks” near Rio Grande City. After camping at Santa Gertrudis Creek just long enough to scout the vicinity, the rangers moved southwest and established a camp at San Antonio Viejo.

Here, Ford found a resilient frontier community that had known as much disaster as prosperity. Among dignified sillar houses occupied by families, humble jacales, and old stone watering troughs dating back to the Spanish era, he found the remains of an old hacienda – perhaps built for Francisco Vela – destroyed decades prior by Comanche or Lipan raiders. The rangers’ tents formed three sides of a square; one of the old buildings, in which they stored supplies, served as the fourth.

On the morning of May 29, 1850, Ford and his rangers were on their way back to San Antonio Viejo, escorting a supply detail to Ringgold Barracks, when they struck fresh Comanche sign. The rangers’ scout, Roque Mauricio, had been snatched from his home in Camargo by Comanche raiders when he was only four years old, grew up to become a respected warrior, and at about age 20, after a raid on Rio Grande City, had been captured by rangers under command of Captain Clay Davis, who persuaded him to switch loyalties and avoid punishment.

Roque quickly located the raiders’ camp. In the ensuing battle, the rangers killed several Comanches and wounded and captured a young warrior who turned out to be Carne Muerto, son of the Penateka Comanche war chief Santana. The young warrior recovered, and the rangers took him to Fort McIntosh, at Laredo and continued on a scouting expedition in Laredo.

A few days later, Comanche raiders struck the camp at San Antonio Viejo, hoping to find and rescue Carne Muerto. The remaining rangers, under a Lieutenant Highsmith, held off the attackers, who left after a two-day siege.

Shortly after being transferred to Fort Merrillin in January of 1851, Carne Muerto escaped to the High Plains, where he joined the Quahada Comanches and led raids against settlers and soldiers until the early 1860s.

Even as Rip Ford’s rangers provided relief from Comanche raids, economic disaster loomed. In 1849, Asiatic cholera struck San Antonio de Bexar, Port Lavaca, Brownsville, and other towns where soldiers returning from the war were mustering out of service. Corpus Christi, which had previously been little used by the army, and thus spared exposure to cholera, became the port of choice, and Laredo the preferred point of entry along the Rio Grande. For a few years, then, trade that had long passed through San Antonio Viejo passed between Laredo, Corpus Christi, and San Antonio de Bexar.

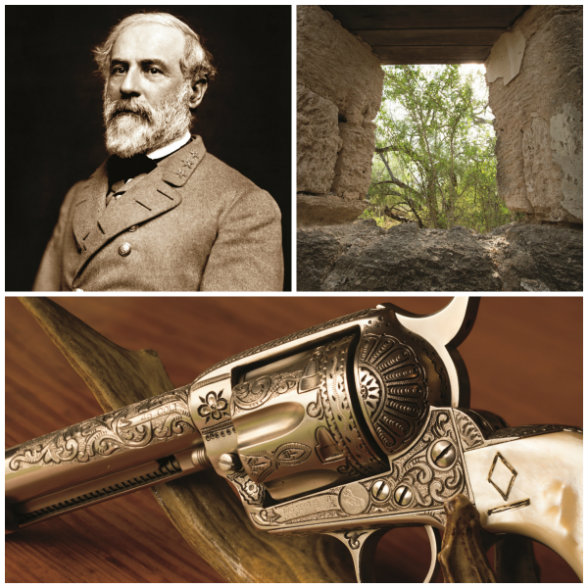

Prior to the Civil War, Colonel Robert E. Lee (top left) often camped at San Antonio Viejo and at neighboring Randado on his journeys between Ringgold Barracks on the Rio Grande and Camp Cooper near present-day Abilene. Early settlers braved more than just the elements. Comanches, Lipan Apaches, and marauders from both sides of the Rio Grande led to the construction of solid-rock homes with built-in gun ports (top right). Manufactured in 1910, Tom T. East’s Colt .45 bears the Diamond Bar brand (below).

The epidemic burned out, and San Antonio Viejo began to recover as the old routes came back into use. In 1857, Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee, on his way back to Camp Cooper from court martial duty at Ringgold Barracks, camped at the “San Antonio Wells,” where, according to his letters, he watched mustangers catch 20 colts and a roan mare, and admired a striking iron-gray mare.

Though its fortunes waned during the tumultuous decade following the US war with Mexico, the community at San Antonio Viejo remained largely intact, maintaining continuity with traditional Spanish-Mexican culture of the rancho. Yet the upheaval of revolution and war, and the uncertainty of the Bourland Commission’s adjudication, would soon seem transient compared to the changes about to be wrought by newly freed economic forces, specifically raw capitalism.

In 1852, those forces appeared incarnate 75 miles northeast of the San Antonio Wells, in Nueces County, where a Corpus Christi businessman and part-time Texas Ranger named Gideon “Legs” Lewis and his new partner, a young riverboat captain named Richard King, established a rough cow camp above a spring-feeding Santa Gertrudis Creek.

Anglos who trickled into the Nueces Strip prior to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo did little to change a seven-century tradition of the rancho. Many married into Mexican families, and became, in nearly every sense, Tejano.

The two decades after the Bourland Commission rulings saw rapid Americanization of Trans-Nueces Texas, in which a way of life extending back to medieval Spain moved inexorably toward profit-oriented enterprise.

Mifflin Kenedy, Richard King’s primary partner and mentor, began purchasing land at Valerio, on the Nueces River and, in 1854, acquired the San Salvador del Tule land grant north of Brownsville. In 1854, King and Legs Lewis added to their holdings the 53,000-acre Santa Gertrudis grant. After Lewis’s murder a year later, King, Kenedy, and James Walworth formed R. King & Company with some 20,000 head of cattle and 3,000 horses. Two years later, the partners purchased some 90,000 acres of the Laureles grant and another 22,000 acres in the Casa Blanca grant north of Santa Gertrudis.

Meanwhile, the settlement at Rancho Viejo continued as a Tejano community supported by surrounding ranchos, especially Las Cuevitas, Agua Nueva, Santa Domingo, Alta Vista, and Randado, with additional commerce from Rio Grande City and Corpus Christi.

On February 23, 1861, Texas seceded from the Union. Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter in April. Even as the war ravaged much of the South, and a Federal naval blockade threatened to strangle a Confederacy dependent on cotton exports and the import of manufactured goods, the chaos of war brought an uneven prosperity to Confederate South Texas.

Mexico remained neutral throughout the war. Its riverboats and lighters carrying cotton could not be stopped by Union boats. Ambitious Anglo ranchers and businessmen like Richard King, Charles Stillman, and Mifflin Kenedy had little trouble arranging for tens of thousands of bales of cotton to be loaded at Rio Grande City and Roma and smuggled by steamboat downriver under Mexican paper, and lightered out to ships waiting to carry the precious cargo to England, France, and, no doubt to the immense satisfaction of rebels Kenedy and King, the northeastern United States.

Richard King’s rancho, which would play a central role in the future of San Antonio Viejo, served as a hub for wagonloads of cotton coming from every cotton-producing region in Texas and the Deep South.

It seems likely that in a smuggler’s economy, San Antonio Viejo, at the intersection of two important roads – one leading to King Ranch – managed the upheaval of war successfully, even as banditry and Indian attacks increased in the chaos and absence of rangers called away to serve the Confederacy. Although disrupted travel made even short cattle drives perilous, enterprising rancheros able to deliver cattle to hungry Confederate forces thrived. The arrival of Union troops under General Nathaniel Banks, on November 2, 1862, and the fall of Brownsville to Union forces in 1864, did little to stop Confederate smuggling.

On April 29, 1862, at Rancho Santa Gertrudis, Richard and Henrietta King welcomed their fourth child, a daughter named Alice Gertrudis. Her name seems fitting. She was born on ground she served the rest of her life. And through her eventual marriage to Robert Justus Kleberg, the King Ranch empire would continue and grow. From that King-Kleberg union came another baby girl, one who would grow rooted in another place in the Wild Horse Desert: San Antonio Viejo.

Although Richard King, Mifflin Kenedy, Charles Stillman, and a few other well-connected Anglo-Texan smugglers prospered during the Civil War, most rancheros in South Texas saw cattle prices drop as low as two dollars per head as restricted travel and difficulty moving cattle to market outside the region caused a local glut, worsened by the punishing winter of 1863—64, which drove tens of thousands of open-range cattle from the Rolling Plains and Central Texas into South Texas. While the event, the first to be known as the “Big Drift,” eventually contributed to the golden era of the northward cattle drives, in the short term, the great overabundance in South Texas spurred cattle thievery, drove down prices, and ruined cattlemen from the Red River to the Texas coast.

Cattle drives resumed and expanded after the war, however. A year after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, tens of thousands of South Texas cattle were being driven up trails to railheads in Kansas and Missouri, or to stock rangeland in the Dakotas, Nebraska, Wyoming, and other southwestern grasslands. Between 1869 and 1885, Richard King’s vaqueros drove some 70,000 cattle to distant markets.

As South Texas recovered from the war, the community at San Antonio Viejo surely shared in the prosperity. Although many Mexican-American vaqueros, including King’s Kineños, drove cattle north, most Tejano rancheros kept their herds close and waited for buyers, of which there were many. The early Reconstruction price of two dollars per head rose as demand soared.

AN AVIAN PARADISE BLOOMS IN THE WILD HORSE DESERT (clockwise from top left):

bobwhite hen; male northern cardinal; eastern screech owl; Rio Grande turkeys; male Altamira oriole; male painted bunting.

In 1875 Lazaro Peña bought 1,920 acres in the old Noriecitas grant, just east of present-day Hebbronville, that included the original crossroads freight station for José Escandón’s settlements. At this same crossing, which had been frequented by ox carts since the Spanish era, he established Peña Station, which became the area’s most important railroad point.

By 1883, the Texas Mexican Railway, which connected Laredo and Corpus Christi and other smaller communities, passed by Pe̱a Station, making it for a short time the busiest cattle shipping point in the country Рmuch to the benefit of San Antonio Viejo and other ranching communities to the south. Even after James Hebbron moved the station a few miles to the west and established the town of Hebbronville, stage coaches and overland freight hauled by mules and oxen continued to pass through Pe̱a Station until 1917, as it lay on the shortest route between Ringgold Barracks and San Antonio and Corpus Christi.

At the height of prosperity, from about 1886 to 1906, San Antonio Viejo included a post office and church to support as many as 100 residents. Oblates from Roma visited periodically to hold services. The community also traded with its own trade tokens, stamped “Fco. P. Pena Guerra – San Antonio Viejo, Texas.” The Guerra family owned stores and other facilities in the town of Guerra, a few miles to the southwest. Traffic along the main trade route from Rio Grande City, which ran through San Antonio Viejo, must have been a boon to the community.

Yet forces conspired toward the obsolescence of the old rancho system. Fencing of the huge haciendas in South Texas and the big spreads on the Rolling Plains ended open-range grazing by 1890. The era of communal roundups that had encouraged cohesiveness in vulnerable, remote lugares, was fast closing.

Even though short cattle drives between ranches and railroad shipping points continued well into the twentieth century, the old methods were giving way to consolidation and efficiency. Worse yet for small ranchos struggling to adapt to unprecedented change, tick fever reduced demand for Texas cattle at northern railheads. A three-year drought beginning in 1881 left precious little grass along old cattle trails. With no route to northern markets, South Texas’s surplus herds swelled and prices plummeted.

Just as the earliest Anglo-Texans settling south of the Nueces learned to ranch and make a life in the Wild Horse Desert, proud old families with lineages back to Nuevo Santander and southward now melded their ways with the Anglo penchant for commerce. A venerable way of life had become a business.

Sometime after the Civil War, a man named Edward H. East made his way from Illinois to Texas. On August 28, 1882, his wife, Hattie, gave birth to a son, Arthur Lee, in Corpus Christi. On December 19, 1889, in what is now Archer County, Texas, where Edward East by then owned half interest in the OX Ranch and served as general manager, the family welcomed another son, Thomas Timmons East.

On January 9, 1893, a third child, a girl, was born to Robert and Alice Kleberg. Named Alice Gertrudis after her mother, she would live an exceptionally long life rooted in the South Texas soil. Through her, San Antonio Viejo’s fortunes would be tied to those of the King Ranch for three decades, and through her, the San Antonio Viejo Ranch would break away to build its own legacy.

In The King Ranch, Tom Lea wrote, “Young Alice and Sarah [her younger sister, Sarah Spohn Kleberg], as they grew up, became tomboy hands at the cow works and roundups. Alice was especially unenthusiastic about school life and school studies at Corpus Christi. Her character – in her growing devotion to range life, to the rides in solitude, to knowledge of and communion with the land and the livestock – bore a marked resemblance to that of her mother’s beloved brother Robert E. Lee King.”

By 1913, the East brothers, Tom and Arthur, were active in the ranching business in Starr County and newly formed Jim Hogg County, owning and leasing tens of thousands of acres, including an 18,849-acre tract immediately north of the San Antonio Viejo grant.

Tom and Alice East worked side by side at San Antonio Viejo, a ranch they sacrificed

to obtain, then lost, and later recovered.

In his short, unpublished memoir on the period, Hart Mussey wrote, “Tom East was a hustler and operating on a large scale, especially for his age.” Tom T. East soon operated on a much larger scale. Manuel Guerra, a powerful figure in Starr County, scion of a great landowning family that had long dominated South Texas politics, owned the entire San Antonio Viejo tract save for a few thousand acres in and around Rancho Viejo. On June 9, 1914, Manuel Guerra died. His widow, Virginia Cox de Guerra, began purchasing several small plots within the larger San Antonio Viejo tract from Hippolito Ramirez and others with undivided interests in the old community.

In December of 1914, Tom East purchased the entire 23,795-acre tract from Virginia Cox de Guerra and bought out his partners in the East, Holbien & Adams venture to become sole owner of 42,644 acres of what had been the Vela and Las Moritas grants. What had been called San Antonio Viejo would soon be called, simply, Rancho Viejo, “Old Ranch,” as Tom East’s headquarters on the Las Moritas tract would be known for a while as Rancho Nuevo, “New Ranch.” Collectively, the two large tracts, and the many thousands of acres that would be added, became San Antonio Viejo.

Tom East had formed a close friendship with Caesar Kleberg, manager of the Norias Division of the King Ranch and cousin of Richard and Robert Kleberg – as well as cousin of Alice Gertrudis Kleberg, whom Tom had been courting. We know little about the courtship or what the King-Klebergs thought of Tom East.

We do know Tom and Alice were married at Santa Gertrudis on January 30, 1915. Tom Lea described the wedding in The King Ranch: “Two daughters of the family were married at the big house when it was finished. In a ceremony held at 8:30 in the morning Alice Gertrudis Kleberg married a young cattleman, Tom T. East. Henrietta was her sister’s wedding attendant and Caesar Kleberg was East’s best man. Minerva King, daughter of Richard King II, played the piano, and Dick Kleberg sang Til the Sands of the Desert Grow Cold. Following a big family wedding breakfast, the newlyweds left directly for San Antonio Viejo, the groom’s ranch south of Hebbronville in Jim Hogg County about 75 miles from Santa Gertrudis, where the young couple established their home and shared the arduous ranch life they both knew and loved.”

Six months later, Alice’s older sister married in a fashion more in keeping with her status: “The big house was the scene of a far more elaborate festivity when Henrietta Rosa Kleberg married John Adrian Larkin of New York. Larkin, who later became Vice President of Celanese, was a companion and Princeton classmate of Tom Armstrong, son of the ranger and ranchman John B. Armstrong,” noted Lea. He summed up his description thus: “The bridal couple took their leave while Princetonians of the wedding party sang Old Nassau, then gave the Princeton cheer, speeding the happy Larkins on their honeymoon in the Adirondacks, a summer home at Croton-on-Hudson, and a town life far removed from South Texas.”

Alice East was her mother’s daughter. While her brother Robert eventually took over management of King Ranch and became a big player in the world of Thoroughbred racing and breeding, and Richard went on to become a prominent attorney and six-term Congressman, Alice, like her mother, with whom she shared a given name, devoted her life to husband, family, and the ground she called home.

With her wedding gift of cash from her grandmother, Alice bought 25 registered cows and a bull from the Cook Ranch. She had them branded with the Lazy Diamond, her personal brand for the rest of her life.

As the newlyweds rode from Santa Gertrudis to their home, San Antonio Viejo, their exhilaration must’ve been tempered by the reality of the challenges ahead. Twenty six-year-old Tom East had assumed enormous debt – a mortgage of $80,000 plus a loan arranged directly with Virginia Cox de Guerra. He’d also bought cows, heifers, and a few steers to stock his ranch, and had sold few cattle the previous year.

Just across the Rio Grande, only 50 miles from ranch headquarters, the Mexican Revolution continued unabated. Banditry remained a constant threat. Rumors flew. South Texans expected an attack by Pancho Villa and his men at any moment.

Long fraught, relations between Anglo-Texans and Mexicans as well as Hispanic Texans grew tenser with the discovery of the Plan of San Diego, a radical manifesto penned not in San Diego, Texas, but in a Monterrey jail cell. The plan cited grievances going back to the US war with Mexico and accused Anglo-Americans of savage imperialism, exclusion of non-whites from public life and institutions, and continued tyranny. Furthermore, it claimed independence of former Mexican territories “robbed in a most perfidious manner” by an imperialistic United States. Most alarmingly, the plan called for the murder of all white males over the age of 16 and the repossession of any funds they might carry on their person. The revolution was to begin in February 1915.

Ranchers took the threat seriously. Much as rancheros had temporarily left their lands because of the threat of Indian raids a century before, several Jim Hogg County ranchers retreated to the Hotel Viggo in Hebbronville.

Whatever their fears, the Easts could afford no such luxury. They had a ranch to run, and that ranch required their presence. During roundup, Tom East oversaw three corridas– 10 men, a boss, remuda man, and cook per corrida – rounding up cattle and driving them to Hebbronville, often as far as 50 miles.

At dusk on March 17, 1916, the Easts drove in from a cow camp to Rancho Nuevo, the present San Antonio Viejo headquarters. Tom got out of the car to check some stock feed in the barn; Alice drove to a corral behind the barn. As Tom started to exit the back door to meet Alice, he glimpsed the glow of several lighted cigarettes in the dark corral. He eased the door shut and backed away in hopes of warning Alice. Before he could exit the front door, she’d driven in among the some 40 heavily armed bandits, who surrounded the car.

In what must’ve been a moment of pure torture, Tom East realized the futility in running to his young wife’s defense and the danger of provoking a violent reaction. He slipped away and made his way on foot several miles through the thorn scrub to a cow camp where he dispatched a messenger to rangers stationed at Hebbronville.

The bandits never laid a hand on Alice. They allowed her to walk to the foreman’s house, where they demanded food. Afterward, they robbed the ranch commissary of $90 and all the boots, shoes, clothes, and groceries they could carry, before catching East horses and riding away.

At midmorning, the county sheriff, Oscar Thompson, and 12 rangers arrived in a truck full of weapons and saddles, and rode away in pursuit. After trailing for some 25 miles, the rangers surprised the bandits in their camp, killing one, wounding several others, and recovering the stolen horses, two mules, saddles, and assorted tack and weapons.

Ironically, half a century earlier, Alice’s mother, barely a year old, was present when another large group of armed men occupied, ransacked, and plundered her home. On December 23, 1863, 80 Federal troops under command of Captain James Speed arrived at Rancho Santa Gertrudis in hopes of capturing or killing the notorious “Rebel agent” Richard King. Instead, after shooting at the front of the house, they shot and killed an unarmed ranch employee, Francisco Alvarado, who’d dashed outside shouting that women and children were in the house. The Federals didn’t find Richard King, who was away trying to arrange for more troop support in the region, but not for lack of searching. Soldiers probed every feather mattress with sabers and bayonets, then, in spite, rode horses through the first floor of the house and pawed through Mrs. King’s personal items before riding away on Christmas Eve with as much plunder as they could carry.

East family members Lica, Tom Sr., Tom Jr., and Robert display their take after a successful hunt with their tracking hounds and their handler, a vaquero named Tiburcio, renowned as a tracker.

By any measure, the 40 Mexican bandits behaved with more decency than did Captain Speed’s Union soldiers.

The couple’s first child, Tom T. East Jr., arrived January 2, 1917, during the worst drought then on record. Rain ceased in 1916, and except for occasional tantalizing sprinkles, wouldn’t return until 1918. Any grass that hadn’t already been cropped by cattle withered away. The conventional fall back of prickly pear proved too risky. At the height of the drought, attempts to burn away spines often ignited the desiccated pads. Some 1,100 East cattle died.

At the same time, bandit raids continued along the border, as did the revolution in Mexico. Tom Junior was barely a year old when bandits again raided San Antonio Viejo, this time taking as hostages Tom East’s friend Claude McGill, a Texas Ranger and cattleman, the foreman and his family, and driver Rosendo Garza. As before, the bandits ransacked the ranch commissary, then forced Garza to drive them toward Hebbronville, where they planned to rob a bank. On the way, Garza dissuaded the bandits, telling them that a lot of rangers were stationed in Hebbronville. The bandits abandoned their plan, returned to the ranch, released the hostages unharmed, and rode for the Rio Grande. A posse of Texas Rangers and other local lawmen pursued and shot dead one bandit before the rest escaped into Mexico.

A second son, Robert Claude East, was born October 5, 1919, and a daughter, Alice Hattie (Lica, pronounced “Lisa”), on November 11, 1920. Like a Comanche mother, Alice often bundled her babies on cradle boards and hung them on posts or tree limbs, in the shade, while she worked nearby.

In the meantime, the Easts added to their holdings, purchasing 22,928 acres from former Texas Ranger Sam Lane and the 14,858-acre Mary Jenson tract at the south end of the ranch. Several smaller additions brought the total to 80,721 acres by the end of 1919.

In 1921, the Mexican Revolution finally burned itself out, to the great relief of ranchers on both sides of the Rio Grande. Worries of banditry began to fade.

Yet Tom East had fallen behind despite long days of battering work and a brisk business selling range horses and such cattle as he could. Despite the three-year drought, men still had to be paid, equipment maintained and replaced, livestock tended. Under terrible stress, cattle couldn’t endure roundups or drives to market or to better pasture. Some 200 square miles of ranchland and cattle were dying. And more, the Easts had three young children at home.

There could’ve been no hiding reality from Alice. The strain must have been almost unbearable at times, the blow to Tom East’s pride terrible even as he knew cattlemen around him were struggling if not failing. Did he keep the severity of his troubles between himself and Alice, or did he discuss the possibilities with his friend Caesar Kleberg and other members of the King-Kleberg family? They would have understood, and surely recognized the signs in any case. A rancher plans for contingencies, but to perpetually plan for record-setting drought would preclude growth.

In March of 1922, the Easts deeded their beloved San Antonio Viejo Ranch to Alice’s maternal grandmother, Henrietta King, for the release of a chattel mortgage on 5,000 cattle. The Easts continued to live on the ranch while Tom served as manager.

Life went on. Cattle had to be branded and weaned and bought and sold, horses broke. In a journal entry dated January 30, 1928, Tom wrote:

Today is my thirteenth wedding anniversary, and I can truthfully say there have been lots of ups and downs in the past thirteen years. Have fought lots of battles, but have not lost any yet. But several come out as a draw.

From the transfer of title in 1922 through 1930, Tom ran his own cattle on the San Antonio Viejo under various leases with the King Ranch in addition to his duties as manager and employee. He cleared thousands of acres of cattle-fever ticks and paid for improvements out of his own earnings.

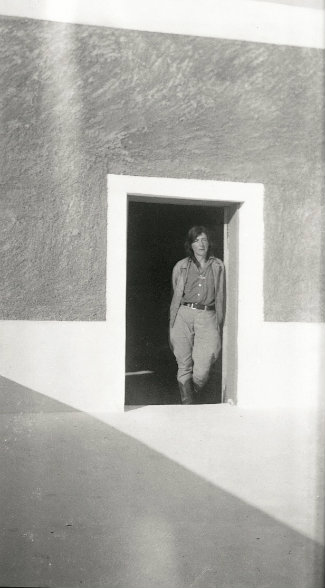

Alice East pursued her interest with the camera; dozens of black-and-white photographs, often skillfully composed, capture life on her beloved San Antonio Viejo. Copies of Horses to Ride, Cattle to Cut can be ordered from EastFoundation.net or WymanMeinzer.com.

Acquisition of some 66,000 acres for release of a mortgage on a few thousand cattle might seem like raw opportunism by Mrs. King and the Klebergs. Certainly, hard bargains of that sort have been common throughout the modern era of ranching, and rare is the great ranch that hasn’t grown on the misfortunes of neighbors. Yet the arrangement, as chastening as it must have been to a proud, ambitious young couple, surely seemed like a godsend to the Easts, for they could remain on the San Antonio Viejo, and the ranch remained within the extended family.

Furthermore, King Ranch suffered financial strains of its own. Before ranchers fully recovered from the drought of 1915—17, post—World War I deflation drove cattle prices down through the first five years of the 1920s. Drought struck again in 1925. Western cattle loan companies went into liquidation; thousands of cattlemen lost their ranches. Henrietta King’s death on March 31, 1925, initiated a complex 30-year trust overseen by Robert J. Kleberg Jr., and a long fight with the federal government over potentially ruinous estate taxes. Rather than ruthlessness, the deed transfer might be seen as painful work by an extended family looking out for its own.

With rare exceptions, Tom East’s intermittent post-1922 journal entries simply record the daily work of a cattleman. Yet close reading makes clear that regardless of deeds and titles, he had not relinquished emotional ownership of San Antonio Viejo, and as much as he carried out his duty as manager and employee, he tended and expanded the property with an eye toward ownership.

Note the clipped, first-person narrative in this undated (probably 1925) entry: “Bought Reed Ranch with 2,000 steers, all horses, mares, goats, and 100 Jersey cows – 17,000 acres of land at $9.00 per acre. Getting dry and need rain bad.” This does not read like a note written by a man who just handled an acquisition for his employer. Tom Lea described the understanding among family members: “The San Antonio Viejo was not a part of the King Ranch proper; though the 66,060.5 acres over in Jim Hogg County did belong to the family corporation, it was in fact the ranching realm of the Tom East family.”

Indeed, in addition to the Reed Ranch purchase, San Antonio Viejo expanded some 5,700 acres during the years of King Ranch ownership through purchase of the G. H. Edds tract (1930), Laborde tract (1932), Barrera and Valle tracts (1933), and Leyendecker tract (1938).

Furthermore, Tom East pursued his own interests, running cattle on tens of thousands of acres at San Antonio Viejo and elsewhere. Two notes written from the period reveal grim realities about range life:

Christobal Garcia was killed at Draper Pens on July 8, 1932. Running a calf and his horse fell with him – breaking his neck.

His brother Modesto Garcia was killed 1920 on San Antonio Viejo by horse falling on him, breaking his neck.

Beyond his spare notes and a vast archive of purchase and sales records and legal documents, hundreds of snapshots, many of them taken by Alice East, provide a glimpse of family life at San Antonio Viejo: Tom Jr. and Robert, at perhaps 12 and 10, unsmiling, rifles in hand. Robert holding a live bobwhite in his left hand, posing with nice white-tailed bucks, Lica kneeling between them. Tom Sr. in the saddle, and Alice in chaps, about to climb into her saddle, both smiling, windmill rising above the trees behind them. And one of my favorites, Lica at about eight, sitting on a roped and tied Brahma bull, blond braids dangling beneath her flop hat, her father kneeling at her side.

Usually, Tom Sr. looks the part of the mature cattleman, the boss, wearing a white shirt, jacket, and tie – even on horseback. Indeed, he moved among the top cattlemen of the era, serving as a director of the Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association for several years, and as Jim Hogg County commissioner.

The East children grew into expert cowhands. They went to school in Kingsville. After grade school, Lica went away to Gunston Hall, a private school in Washington, D.C. On January 1, 1935, 18-year-old Tom T. East Jr. took over as manager of the San Antonio Viejo Division, freeing Tom Sr. to pursue his own interests in addition to serving as a senior member of the King Ranch management team. Tom Jr.’s journal entries are no less understated than his father’s. He notes his first day on the job:

Tom East started work as foreman of San Antonio Viejo Ranch today. Corrida gathered remuda.

A few weeks later, Saturday, March 16, his parents’ stoicism comes through:

Gustavo Ramirez died this morning from heart failure. He died with the wagon reins in his hand. Worked the Moritas today cutting out 175 McGill steers and sending them to San Pablo. [Running W] herd taken to Norias trap.

On Monday afternoon, November 29, 1943, while visiting family at Santa Gertrudis, King Ranch, Tom T. East Sr. suffered a heart attack and died in Lica’s arms. He was 54.