Horse Power

Horse Power

By Henry Chappell

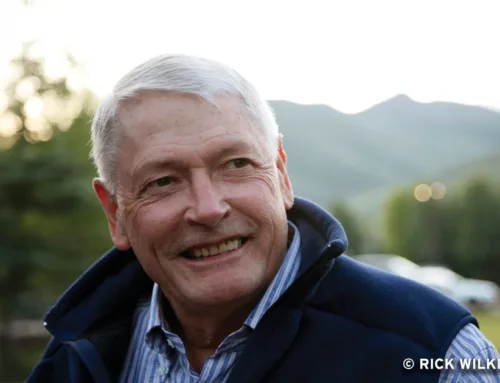

LR_KingRanch-HorsePower-01

It’s an overcast December morning, and that’s a good thing in South Texas. The temperature is in the mid-60s. It could be 20 degrees warmer, and I know for a fact it could be 40 degrees colder. I’m perched atop a wooden fence at a cow camp south of King Ranch headquarters. In the dirt below, a crew of cowboys is working more than 200 calves in the Ebanito pens. Most city folk would find Ebanito a tad remote. (The truth is, they would never find it, not on the ranch’s 825,000-plus acres, and neither could I.) But Ebanito is a storied venue, a favorite of generations of King Ranch family members, and an ideal setting to watch top hands ply their craft.

Robert Silguero eases his horse, a stocky gelding named A Lil Bit O Flash, in and among the red calves. A fifth-generation Kineño, Robert swings his riata like a gunslinger twirling a .45. His mount, a son of King Ranch stallion Marsala Red, is equally cool under pressure. The moment Flash senses the rope go taut, he quickly spins and proceeds directly toward the branding crew. Once the calf is in capable hands, Robert loops his rope and guides Flash back toward the huddle of red beeves.

Los Kineños

Gaucho, paniolo, stockman, vaquero — the term for cowboy changes from region to region and country to country. As the ancestral home of American ranching, King Ranch has its own moniker: Kineño, a word whose etymology can be traced back to Richard King (1824–1885) himself. For more than a century and a half, those who labor on the ranch this rugged riverboat captain forged out of the Wild Horse Desert have been known as Kineños, the King’s Men.

Below me in the rich, dark dirt, half a dozen Kineños are doing exactly what their fathers and grandfathers and great-greats did right here at Ebanito and at dozens of other cow camps on the great ranch’s four divisions. No doubt a Kineño from Captain King’s day would recognize countless aspects of today’s chores: the teamwork, the techniques, and the traditional gear. What he wouldn’t recognize is the horseflesh.

In the mid-nineteenth century, horses in South Texas were much more compact. Descended from the wild mustangs from which the Wild Horse Desert takes its name, these hardy mounts were survivors. Three centuries of brutal selection pressure by man, beast, and Mother Nature had instilled in the Spanish mesteño an ability to do more with less. Rounded up as two-year-olds, they were completely unfamiliar with human hands, let alone saddles, bits, and bridles. They were corralled and broke using methods that would make any horseman wince.

Captain Richard King

Richard King chose only the best mares for his manadas, and he sorted these bands of broodmares by color. In 1868, he traveled to Kentucky to acquire Thoroughbred stallions to cross with his mares. Through selective breeding to Thoroughbred bloodlines, the average size of a King Ranch horse gradually increased to more than 15 hands. The captain found a ready market for the get of these mares. Both the US and the Mexican armies were eager buyers. There were other interested parties, but they didn’t care to pay. Between 1869 and 1872, King Ranch lost nearly a thousand horses to rustlers.

The best horses? Captain King kept those for himself and his Kineños.

James Clement III warms up a grandson of Mr. San Peppy, known affectionately as “El Diablo,” near Santa Gertrudis Creek.

Captain James Clement III

It takes about 30 minutes for Silguero and Flash to empty the pen of the first lot of calves at Ebanito. By the time they finish, both are bathed in sweat. So too are the Kineños branding the calves, including Cameron Nelms, the cow boss, and James Clement III, a sixth-generation descendant of Captain King. Other than Silguero and Flash, no one has an assigned task. Everyone works interchangeably, including Captain King’s great-great-great-grandson. I can assure you, however, that these men do not toil wordlessly. The camaraderie is palpable; laughter, warnings, and quick commands are bandied about. “That’s the way we work at King Ranch,” James says. “That’s also the way they work at the Beggs, my mother’s family’s ranch.”

An infantry captain in the Marine Corps Reserve who deployed with Seventh Marines in Afghanistan’s Helmand province, the 31-year-old’s bio also includes several years working on big ranches in Australia and Florida as well as cowboying on King Ranch’s Encino Division. He always looks forward to the long drive out to the Rolling Plains to work cattle with two uncles, George and Ed Farmer Beggs. Those trips are fewer, however, now that he manages King Ranch’s Quarter Horse Division.

The Old Ways

A fresh roper, Rick Falcón rides into the pen. Barely in his twenties, Falcón, like Silguero, is the most recent member of his family to work on King Ranch. Like Flash, Falcón’s mount works calmly, ever sensitive to the tension of the rope. This process continues until the pens are empty. By noon, every hand has taken a turn roping. Only then does the crew break for a hearty lunch at the Ebanito Hunting Camp: carne guisada, pan de campo, charro beans, and gallons of iced tea.

Dragging calves to the fire is old school. There’s many a cattle operation in North America that accomplishes the same chores with a mechanical squeeze chute. The cow boss knows this. But Cameron insists that his hands rope and brand as their forefathers did. It’s what makes a Kineño a Kineño. And it’s one thing that makes a King Ranch Quarter Horse a rock-solid cow horse.

After Captain King’s death in 1885, a son-in-law, Robert Kleberg Sr., and Kleberg’s nephew, Caesar Kleberg, augmented the ranch’s manadas with Standardbred and Thoroughbred bloodlines. Occasional infusions of Arabian, Morgan, and Kentucky Saddlebred were also added. Although first and second Thoroughbred crosses to the captain’s Spanish mares produced excellent ranch horses, the Klebergs opted not to perpetuate the old Spanish lines. Instead, they achieved greater success by introducing Standardbred bloodlines, which better tolerated the wilting South Texas sun. King Ranch Standardbreds excelled as carriage horses, and the Klebergs found a ready market for them in the years before the Model T.

The Sorrel Horse

But the need for a calmer, more compact, and agile cow horse was becoming apparent. Robert Kleberg Jr. fell in love with a manada of beautiful mares known as the Wax Dolls just up the road from King Ranch in Alice. The only problem was they were owned by a savvy Quarter Horse breeder named George Clegg. Kleberg lacked the authority to buy one, but his cousin Caesar could.

In 1916, one of the Wax Dolls and her suckling colt caught Caesar’s attention. He asked Clegg what he’d take for “a colt like that.”

“One hundred and twenty-five dollars,” Clegg said.

“I’ll take him,” Caesar replied.

Clegg protested, saying he didn’t mean that particular colt, but Caesar held him to the deal. In short order, mare and colt were driven 25 miles to King Ranch. A few months later, the colt was weaned and the mare returned to Clegg.

This Toni Frissell still from 1943 captures Kineños moving a remuda of cow horses at daybreak.

Old Sorrel

The young colt was especially easy to train. As he matured, he distinguished himself under the most demanding conditions. Known simply as “the Sorrel Horse” and later as “Old Sorrel,” he transformed the King Ranch horse herd from respectable to one of the world’s finest. Exceptional in his confirmation, temperament, and cow sense, Old Sorrel also transferred his qualities to his get. (By comparison, King Ranch’s most famous runner, Triple Crown winner Assault, was a disappointment in the stud barn.)

An initial breeding of Old Sorrel to 50 of the best Thoroughbred mares produced an impressive crop of foals, including a son named Solis, who was then bred to daughters from the same band of mares. The results proved to be so promising that King Ranch proceeded with a line-breeding program to preserve and perpetuate the best qualities of Old Sorrel and Solis.

Wimpy

Two decades later, Bob Kleberg Jr. and several other prominent horsemen formed the American Quarter Horse Association to maintain breeding records, set conformation standards, and establish rules for competition. At their first meeting, during the 1940 Southwestern Exposition and Fat Stock Show in Fort Worth, the founders elected to issue the first registration number in the stud book to the winner of the 1941 stock show.

The following year, that honor was bestowed upon a double grandson of Old Sorrel, owned by King Ranch, named Wimpy. Over the next 30 years, descendants of Old Sorrel ridden under King Ranch ownership earned millions in competition and won scores of major championships. To this day, the blood of Old Sorrel courses through the veins of every King Ranch Quarter Horse.

In 1934, Bob Kleberg traveled 100 miles to Goliad to buy a mare from John Dial. During the course of the visit, Dial showed him Chicaro, a Thoroughbred stallion of impeccable breeding. Chicaro’s racing career had been mediocre, and he nearly died from neglect. But Dial recognized his potential, bought him right, and nursed him back to health. Kleberg saw in the stallion’s build the musculature he’d long admired and hoped to bring to his Quarter Horse line. The big bay returned to Santa Gertrudis.

King Ranch Thoroughbreds

Now in possession of a racing Thoroughbred with excellent bloodlines, Kleberg sought out even better mares. On a trip to Lexington, he spotted Cornsilk, whom he later described as the most perfect mare he’d ever seen. As luck would have it, she turned out to be by Chicaro’s sire, Chicle. In 1936, Kleberg bought Cornsilk and seven other exceptional mares at Saratoga. Development of the King Ranch Thoroughbred stable had begun in earnest.

The ranch’s Thoroughbred stable took a giant step forward when legendary trainer Max Hirsch convinced Bob Kleberg to buy the 1936 Kentucky Derby and Preakness winner, Bold Venture. Soon, the brown-and-white Running W silks became a regular fixture in the winner’s circle. Split Second, Dawn Play, and Ciencia won the Selima at Laurel, Coaching Club American Oaks, and the Acorn Stakes at Belmont Park.

King Ranch’s Assault remains the only Texas-bred runner to win the Triple Crown. The son of Bold Venture dusted the field by a record eight lengths to win the 1946 Kentucky Derby.

Assault

A chestnut son of Bold Venture, out of Igual, was born at King Ranch in 1943. His name was Assault. The ranch’s Thoroughbred program was about to reach its zenith. During his three-year-old campaign, the Club-Footed Comet became the first, and to this day the only, Texas-bred runner to win Thoroughbred racing’s Triple Crown. In 1950, Assault’s half-brother, Middleground, just missed pulling off the same feat. He did, however, win the Kentucky Derby and the Belmont Stakes.

When Bob Kleberg died in 1974, his granddaughter Helen “Helencita” Alexander stepped in to manage the Thoroughbred stable. Only 24, she’d spent much of her life at her grandfather’s side, learning the business of breeding, training, and racing Thoroughbreds.

“Like a lot of young people, I had strong opinions, but not much experience,” she says. “Early on, my grandfather recognized my interest and passion. He saw that I knew all about pedigrees, so whenever people gathered to make decisions about the Thoroughbred operation, he made sure I was there to listen and put in my two cents.”

Helencita quickly realized that Thoroughbred breeding and racing could be prohibitively expensive. To increase cash flow, she offered a few yearlings for sale. Several fetched considerable prices.

“Even though we’d done pretty well, we still weren’t able to put a lot of money back into the business,” Helencita says. “I felt we needed a bigger investment if we were going to continue to be successful, but the family wasn’t that interested in Thoroughbreds.”

Helen “Helencita” Alexander

In 1988, King Ranch sold most of its racing Thoroughbreds, but Helencita never lost her passion. She established Middlebrook Farm in Lexington and has served on the Breeders’Cup board of directors. She is a member of the Jockey Club and is a former president of the Thoroughbred Owners and Breeders Association.

Tio Kleberg

In 1971, Stephen “Tio” Kleberg returned to King Ranch after graduating from Texas Tech and serving a two-year stint in the U.S. Army. The decades-long focus on Thoroughbred racing was readily apparent.

“We had excellent brood mares, one or two bands at each ranch division, and some stallions,” Tio recalls. “My father and I would grade the foals and select 30 or 35 for the annual fall sale. Then I began to notice that it was harder and harder to get really top colts. My assessment was that we had great mares but no stallion power.”

Tio suggested to his father that he pick a couple dozen mares and send them to outside stallions.

“Go ahead, but you won’t have any luck. Good breeding stallions are very hard to come by,” Dick Kleberg responded.

Tio and Joe Stiles, who ran King Ranch’s horse operation, went to competitions to find top stallions. They selected three and put six or seven mares with each one. Just as the elder Kleberg predicted, they got some great offspring, but not a single breeding stallion.

In 1974, Tio and Joe met Buster Welch while he was campaigning for the National Cutting Horse Association (NCHA) on yet another Old Sorrel descendant. This one was named Mr. San Peppy.

Tio Kleberg pilots two-time NCHA Open World Champion Mr. San Peppy at Norias.

Peppy San Badger

“We really took a liking to Mr. San Peppy, his confirmation, and his breeding, including King Ranch breeding,” Tio says.

Afterward, the two horsemen went to Sweetwater to dicker with Buster. Tio offered to send mares to breed to Mr. San Peppy in hopes that Welch would sell his stallion.

“We started weaning those colts in the fall of 1976, and they were truly outstanding,” Tio says. “We went back to Sweetwater, made the swap, and bought Mr. San Peppy with the agreement that Buster would come help us for a year to get the horse program put together.” By this time, the stallion was a two-time NCHA World Championship and an AQHA World Cutting Champion.

During that initial year, Tio, Joe, and Buster picked the very best brood mares from each division – about 200 total. “We were really tough on them, their feet, legs, and disposition,” Tio says. From this evaluation, the best 50 were selected and bred to Mr. San Peppy. Buyers were thrilled with the get.

In 1977, Buster received a call about a son of Mr. San Peppy owned by Joe Kirk Fulton named Peppy San Badger. The trainer asked Buster to help him campaign the young stallion. Buster rode him and loved him. Tio had to have him. Another horse trade was in the works. In the upcoming NCHA Futurity, Fulton could take the glory as Little Peppy’s breeder, but he was to be King Ranch’s horse.

“So Buster showed him, and we won the Futurity. The rest is history,” Tio says.

Buster Welch and Peppy San Badger cut a cow out of a sea of Santa Gertrudis.

Little Peppy

Peppy San Badger – “Little Peppy” – won the NCHA Futurity in 1977, the NCHA Derby in 1978, and was the NCHA Reserve World Championship in 1980. He was inducted into the AQHA Hall of Fame in 2008. Together, Mr. San Peppy and Peppy San Badger exerted an incalculable influence on the Quarter Horse breed and tens of thousands of top-notch cow horses.

Mr. San Peppy remains Tio’s favorite. “The tougher it was, the better he liked it. He was Dick Butkus, and Little Peppy was Cassius Clay – a great athlete with great finesse.”

Steve Knudsen signed on with King Ranch during these heady times. He spent the next four decades working in numerous roles before becoming manager of the Quarter Horse operation. Last year, he passed the baton to James Clement III. The two spent a full year in the harness together before Steve stepped down.

“I learned a ton from Steve that year,” James says. Their year together was a cram course. “I thought I’d be working for him for years. I had no idea I’d be stepping in a year to the day after I came to work for him.” Prior to retiring, Knudsen set in motion the purchase of a stallion with the potential to enhance the genetics at King Ranch Quarter Horses much like Mr. San Peppy and Peppy San Badger did in the 1980s.

Rocking W Dispersal Sale

Steve and James were browsing through the Western Bloodstock catalog for Alice Walton’s dispersal sale when Steve said, “That would be a heck of a thing for King Ranch to buy that horse.” By “that horse,” he meant The Boon, a son of Peptoboonsmal, whose lineage includes Old Sorrel, Mr. San Peppy, Peppy San Badger, and High Brow Cat.

“Sometimes, your program needs a genetic shock from outside to get you to the next level,” James says. “The Boon brings that, and at the same time, preserves our lineage back to Old Sorrel.”

The Boon

Foaled in 2008, The Boon suffered a severe leg injury as a three-year-old and missed the Futurity. But Pattie Haney, Rocking W’s stallion manager, patiently nursed him back to health, and the Rocking W’s in-house trainer, Jesse Lennox, readied The Boon for competition.

“I’d never ridden a horse that could stop like him,” Jesse says. “He’s so powerful and reachy. That extension comes down from Boon San Sally and a lot of others in Ms. Walton’s Rocking W program. The Boon is the pinnacle.”

According to elite trainer Phil Rapp, “The Boon is tremendously athletic and unbelievably cowy.”

After two years in a cast, The Boon had to prove himself. He started campaigning as a five-year-old and racked up winnings of $76,000 over the next two years.

When it came time for the dispersal sale, King Ranch faced a challenge: The Boon would be its first purchased stallion since Futurity winner Dry Doc in 1983. (Buster Welch rode Dry Doc to victory in the 1971 NCHA Futurity, defeating his son Greg on Mr. San Peppy.)

Overt interest by such a prominent bidder would have undoubtedly driven the price of The Boon higher. Instead of showing his hand, James relied on the expertise of Joe Stiles’s daughter, Heather, who performed extensive research and supported King Ranch throughout the acquisition process.

Alice Walton

“The Boon is my favorite horse I have ever raised. The Boon has a heart as big as Texas. There is no place I would rather see him than the world-famous King Ranch,” said Alice Walton in a press release.

“This horse wants to work,” James says. “He’s stout. He wants to cut a cow. He’ll step up to a cow and challenge it. You can see the excitement in his face. A lot of people are comparing him to Little Peppy.”

James pauses. Then he shifts perspectives. “When the Kineños see us buy a big-time stud like The Boon, they see our commitment to mounting them with the very best. There’s pride, a morale boost, and curiosity. The opportunity to throw a leg over a cow horse of this caliber helps us retain our best employees as well as recruit outside talent.”

Ben Espy shadowed his Uncle Tio as well as Dr. John Tolkes, King Ranch’s longtime equine veterinarian. After studying biology at Duke, he decided to become a veterinarian himself and got his DVM at Texas A&M. He applauds the acquisition of The Boon.

Says Ben, “The Boon is such an important step for King Ranch Quarter Horses. “I’m forever grateful to Tio and the other board members who supported our plan to buy an outside stallion to diversify the bloodlines.”

Joe Stiles believes that The Boon will be a game changer. “He could mark the reentry into the big time for this program. You can’t go up against the big boys with ranch horses. You need outside blood, something known and popular bred. The Boon brings to King Ranch what Mr. San Peppy brought back in the day.”

Helen “Helenita” Kleberg Groves

Bob and Helen Kleberg’s only child reigns as King Ranch’s matriarch. Helen “Helenita” Kleberg Groves was at her father’s side when the creation of the AQHA was first discussed at Santa Gertrudis. She worked cattle, competed in cuttings, and fox hunted – all on King Ranch horses. She too is excited about the acquisition of The Boon.

“I’m delighted that family members have taken such an active interest in the operation,” Helenita tells me. “For my father, it was always about performance, performance, performance, whether he was talking about dogs, cattle, or horses. Ultimately, I want to see our Quarter Horses out in front again.”

There’s a long stretch of lawn in front of the Ranching & Wildlife Headquarters at King Ranch. A series of small granite markers lies tucked away along its northern edge. These small rectangular memorials comprise King Ranch’s horse cemetery. The simple granite memorials are modest in every respect save one: terse mentions of larger-than-life achievements: foundation sire of King Ranch, Triple Crown winner, Kentucky Derby winner, National Cutting Horse Association World Champion, National Cutting Horse Futurity Champion.

Old Sorrel, Hired Hand, Assault, Middleground, Anita Chica, Mr. San Peppy, Peppy San Badger – this scant patch of St. Augustine grass is the final resting place of immortals. One day, decades from now, I believe The Boon will join their number.

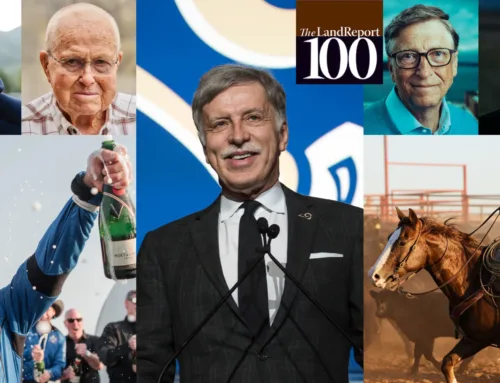

A NEW SIRE. King Ranch Quarter Horse Manager James Clement III and King Ranch Chairman James Clement Jr. celebrate the successful acquisition of The Boon.

Originally published in The Land Report Texas 2016.