Reagan Ranch

Reagan Ranch

An Excerpt from Reagan: His Life and Legend

By Max Boot

Photography By National Archives

LR_ReaganRanch-01

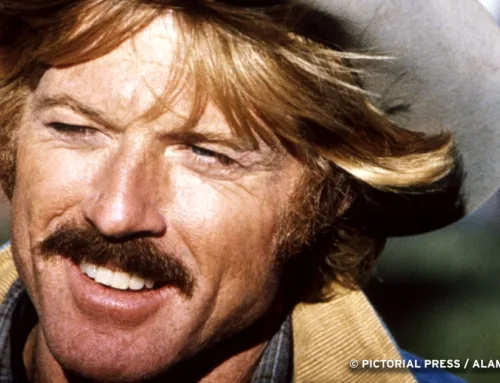

MAN OF THE PEOPLE. When our 40th president relaxed and recharged at his California ranch, the American people saw a septuagenarian who not only loved his land but was capable of hard work.

The White House is a museum, an office building, and a five-star hotel all in one. Most newly elected presidents appreciate having some 90 household staff at their disposal but find it hard to adjust to a life in which they are not allowed to drive or shop for themselves — or even to walk the streets anytime they feel like it.

Their movements are tightly constricted by the demands of security; their every public utterance, no matter how prosaic, is instantly transcribed and treated as news. Bill Clinton described 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue as “the crown jewel of the federal penitentiary system,” and Barack Obama complained, “It’s like a circus cage, and I’m the dancing bear.”

This excerpt may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Gilded Cage

Although he had lived much of his life in the public eye, Ronald Reagan also expressed frustration at what he described as a “bird-in-a-gilded-cage sense of isolation” once he moved into the White House on January 20, 1981. More than once he would stare out the window, envying the freedom of ordinary people as they walked by on Pennsylvania Avenue.

In early February 1981, he wanted to continue his usual practice of going to a store to buy First Lady Nancy Reagan a Valentine’s Day card. His Secret Service detail took him to a nearby gift shop. The result, as an aide wrote, was “total pandemonium, as stunned customers milled around and a crowd of onlookers formed.”

“That was just about my last shopping expedition outside the White House,” Reagan ruefully wrote. “It caused such a commotion that I never wanted to do that to a shopkeeper again.”

ANNIVERSARY GIFT. The Reagans celebrated their 30th anniversary in high style with a new riding mower.

Little wonder that Reagan sought, at every opportunity, to escape the gilded cage. On most weekends, the Reagans headed to Camp David, the presidential retreat in the Catoctin Mountains of Maryland. But whenever there was a longer break, they took off for their spartan, 688-acre ranch in the hills near Santa Barbara, California.

Anyone who wants to find out who Ronald Reagan really was needs to visit his ranch, now a museum maintained by the Young America’s Foundation. The ranch was his favorite place in the world — and a remarkably modest home for a Hollywood celebrity, much less a president of the United States.

Like Lyndon B. Johnson and George W. Bush, Reagan cultivated a down-home image at his ranch. The pictures of Reagan riding a horse or wielding a chainsaw suggested he was still vigorous even though he was nearly 78 by the time he left office in 1989. And his simple, spartan life at the ranch showed the voting public that he had not let power and celebrity go to his head.

It was the version of Reagan revealed at the ranch — affable, modest, unaffected, down-to-earth, hardworking — that lay at the core of his political appeal. Contrary to the popular perception, he seldom played a cowboy in the movies — he complained to his bosses at Warner Bros. about being cast in romantic comedies rather than in Wild West shoot-’em-ups — but at the ranch, he came to embody the popular stereotype of the cowboy.

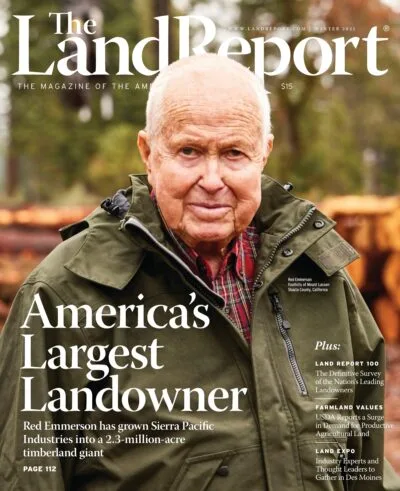

REMARKABLY MODEST. The Western White House was actually a century-old adobe homestead that totaled just 1,500 square feet.

A Modest “Ranch in the Sky”

The Reagan ranch — the third he had owned, after earlier spreads in Northridge and Malibu, California — is located amid the chaparral and grasslands of the Santa Ynez Mountains. The Reagans bought the property in 1974 for $527,000 near the end of his second term as governor of California. It featured a tiny adobe house that had been built in 1872 and a small lake that provided its water supply. There were few amenities, but Reagan immediately fell in love with the place, which offered sweeping views all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

The previous owner had called it Tip Top Ranch. The Reagans renamed it Rancho del Cielo, or Ranch in the Sky, and the former governor set about making it livable with help from two former state police bodyguards who became close friends: Willard “Barney” Barnett and Dennis LeBlanc. Working with a contractor, they expanded the house, replaced the roof, added a patio, and built a wooden fence around it.

When they finished in early 1977, the house was still modest. It had only five rooms totaling just 1,500 square feet, and the downscale Western furniture and décor — which looked as if it had been scavenged from a flea market — would never pass muster with Architectural Digest. The appliances were made by Reagan’s old employer General Electric, not a fancier brand like Thermador or Sub-Zero. The countertops were Formica, not marble. The bookshelves were full of well-thumbed volumes Reagan had read rather than the unread, leather-bound books favored by interior decorators.

Death-Defying Chores

Reagan was always determined to do much of the work on his property personally — and the work never ended. His son Ron Reagan recalled an episode in the late 1970s when, as a teenager, he was enlisted to help his dad build a patio. Reagan wanted to fashion it out of native sandstone, so the two of them hopped in an old red jeep with a trailer attached. The two men grunted and groaned as they filled the trailer with as many rocks as it could carry, then headed back to the house.

But rather than going along the flat, winding road they had taken there, Reagan decided to return via a shortcut straight over a hill. After getting about halfway up, the jeep began to groan and strain. It wouldn’t go any farther, even with his foot all the way down on the gas pedal. Then it began to roll backward. As they picked up speed going in the wrong direction, the younger Reagan “was fighting to maintain sphincter control,” while his dad “looked almost psychotically unconcerned.”

Somehow Reagan managed to maneuver the jeep back to level ground, and, rather than admit defeat, he insisted with characteristic stubbornness on going back up the hill. It took “four lip-chewing, throttle-grinding, pant-sharting attempts before we finally conquered the ridge,” Ron wrote. But it was worth it: “To this day,” he conceded, “the stone patio gives the old house a handsome, rough-hewn look.”

HOME OFFICE. Chief of Staff Howard Baker (center) and National Security Advisor Colin Powell (right) brief President Reagan in November 1987.

Western White House

When Ronald Reagan became president, his ranch became known as the Western White House. A helicopter pad was added, and temporary buildings were erected to house the Secret Service agents and aides who accompanied the president whenever he traveled. In all, there were roughly 175 people at the ranch at any one time when Reagan was in residence. Along with rattlesnakes and rabbits, the property was now roamed by Secret Service sniper teams. “But,” as Reagan noted in his diary, “it is all temporary & … minimal in its effect on appearance.” The ranch remained extremely rustic, primitive, and isolated — just as its owner wanted it.

Reagan spent most of his time there either horseback riding or doing ranch work. Riding was a new challenge for the Secret Service, which had to set up a riding school for its agents. John Barletta was one of the few agents who was already proficient on horseback; he had learned from the Boston Mounted Police, where his father had been a police officer. He earned Reagan’s respect, he told me one sunny afternoon at the ranch, by keeping up with him on horseback; the president was an excellent rider in the English style. (He usually wore Dehner riding boots, jodhpurs, and a long-sleeve shirt.)

Reagan treasured his solitude, but that wasn’t really possible for the president, even on horseback. Trailing behind him would be a Humvee carrying Secret Service agents, a doctor, a military aide with the nuclear football, and secure communications equipment.

While Barletta was often at Reagan’s side during morning horseback rides, the president’s companions in afternoon ranch work — cutting firewood, clearing brush, repairing the fence, pruning trees — were Barney Barnett and Dennis LeBlanc. The white-haired Barnett, who was 68 in 1981, was retired from the California Highway Patrol. LeBlanc was a younger man — he was 35 in 1981 — who, after leaving the state police, had worked as a Reagan advance man and then a White House aide.

No Talking Politics

Reagan had long been a regular at ritzy black-tie events, but he preferred getting sweaty and just being “one of the guys,” LeBlanc told me. “No matter what the day was, we’d be cutting or building something. He didn’t have any other down-to-earth, working, get-dirty type friends. He just loved getting dirty and working with his hands.”

What did they talk about while working? “No politics,” LeBlanc said. “All we did was talk ranch stuff or family stuff.” But they were just as happy to pass the time in companionable silence. When asked by a journalist what he “really” thought about while “chopping all that wood,” Reagan replied with a two-word answer worthy of the famously taciturn Calvin Coolidge: “The wood.”

Stingy Rations

After a hard day’s labor, all three men would be exhausted and head back to the house for dinner with the first lady. “Man, I could eat a house,” LeBlanc would think to himself. But the actual menu was stingy. Nancy Reagan never cooked, so the food was prepared by their longtime housekeeper, Ann Allman. The petite first lady watched her figure (she was a size 2) and made sure “Ronnie” did too. There was only one plate of food per person, and the men would get up almost as hungry as when they sat down, but the unassuming president never complained or asked for seconds.

After dinner, all four of them — Ron and Nancy, Barney and Dennis — would settle down in the living room to watch a television show like Murder, She Wrote, starring the redoubtable Angela Lansbury. By 9 p.m., the three men were usually so exhausted that they fell asleep in front of the set. Nancy would gently tap Dennis on the foot to let him know it was time to go to bed. He and Barney would shuffle out the door. Sometimes, if they were lucky, the housekeeper would sneak them a few cookies to take back to their trailer. The president and first lady then headed to their modest bedroom.

Best Buddies

LeBlanc said that the late Barnett “was the president’s best buddy: They were one year apart, and their birthdays were the same day — February 6. He was the only guy that I knew that could say, ‘God damn it, Governor, you can’t do it this way,’ in regard to building something if the governor wasn’t doing it correctly. And the governor would say, ‘Yeah, okay, Barney, you’re right.’ How many other friends could talk to him like that?” (Barnett, who had been Reagan’s driver in Sacramento, still called him “governor” even when he was president.)

LeBlanc, too, became closer to Reagan than just about anyone. He was so torn up when his old friend died in 2004 that he couldn’t bear to go to the funeral, he told me. He simply sat at home, watching the television coverage and sobbing.

A man who always remained down-to-earth no matter how high he climbed, Ronald Reagan arguably had a more intimate relationship and a truer friendship with his blue-collar buddies at the ranch than he did with all the grandees, such as Walter Annenberg or Alfred Bloomingdale, with whom he hobnobbed at glittering galas. That was Nancy’s circle. Barney and Dennis were Ron’s guys. “They were, in my opinion, his best friends,” Reagan’s long-serving secretary, Kathy Osborne, told me.

READY TO RIDE. An accomplished horseman, the president’s Secret Service detail was routinely challenged by his superior riding skills.

Reagan never felt happier or more relaxed than when he was engaged in backbreaking labor at Rancho del Cielo. Nancy Reagan, by contrast, preferred to spend time in Beverly Hills and rode horseback only reluctantly, but she tolerated the visits because she knew how good it was for her husband physically and spiritually. If Rancho del Cielo wasn’t heaven, Reagan often said, it “probably has the same zip code.”

Reagan was often criticized for taking too many vacations, especially compared with Jimmy Carter, who took only 97 days off during his four years in office. But, while Reagan spent more time on vacation or at a second home (335 days) than Bill Clinton (174) or Barack Obama (235), he spent fewer days vacationing than George W. Bush (533). Donald Trump, who spent at least 277 days in Palm Beach and Bedminster, New Jersey, during his single term, was also on a pace to exceed Reagan (although he spent far less time at Camp David).

Political Payoff

There was no political calculation in Reagan’s frequent trips to the ranch — he genuinely loved going there — but he earned a significant political payoff nevertheless. Two of his biggest vulnerabilities as president were the perceptions that he was too old for the job — he was the oldest president until that point, since surpassed by Joe Biden — and that he pursued policies that favored his wealthy supporters at the expense of the less fortunate.

If Reagan had spent his vacation time taking it easy at glitzy destinations such as Palm Beach, Martha’s Vineyard, or Hyannis Port — favored by Presidents Trump, Obama, and Kennedy, respectively — that would have reinforced the impression that he had lost his youthful vigor and was far removed from the experiences of ordinary Americans.

Many reporters and historians were frustrated by Reagan’s lack of self-awareness or intellectual depth, but most of the public didn’t care. They liked the seemingly simple, down-to-earth guy who loved his country and liked nothing better than to engage in manual labor. Reagan, for his part, often said that doing ranch work was his form of therapy. Few presidents have ever gained so big an emotional and political payoff from their choice of vacation destination.

Adapted from Reagan: His Life and Legend by Max Boot. Copyright © 2024 by Max Boot. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.”

RANCH HAND. The 77-year-old, shown here in 1988, thrived at Rancho del Cielo.