Colorado’s Great Divide

Colorado’s Great Divide

By Cary Estes

LR – JE_Canyon-01

Colorado is cleaved by a great divide. Known as Interstate 25, the highway runs due north from Fishers Peak State Park at the New Mexico state line through the Mile High City and into Wyoming. To the west of I-25, the Rocky Mountains rise majestically. Significant portions of this breathtaking terrain belong to federal and state entities. To the east of I-25, privately owned, shortgrass prairie predominates.

These two remarkably different geographies represent two markedly different mindsets, and for more than two decades, Ken Mirr has been bridging this great divide, connecting public and private perspectives through the skillful application of conservation easements.

A native of Indiana, Mirr studied law at the University of Denver. Juris Doctor in hand, he worked as a public lands attorney, assisting ranchers, ski resorts, and natural resource companies with land-related matters. In 2005, he founded Mirr Ranch Group, a brokerage that specializes in legacy and sporting properties with conservation values.

Conservation Options in Colorado

“In Colorado, we live in the lap of luxury when it comes to conservation options and opportunities,” Mirr says. “I understand the balance between recreational, grazing, and other uses of public lands and how that impacts ranching on private lands. Such use of public lands is vital to their stewardship. At the same time, private ranches have greater ecological diversity than any other landscape in the West. These islands of private land link with the public lands to create even more significant biodiversity.”

Such opportunities don’t come without challenges, particularly when it involves a third party monitoring an easement.

“When you start talking about a land trust or potentially a government agency having involvement in the affairs of your property, it sets off alarm bells,” Mirr says. “Folks say, ‘Hey, we don’t want anybody in our business.’ This goes to the core of owning land in America. You have inalienable rights.”

But there’s a key caveat.

“These easements are voluntary. They’re negotiated. Nobody is imposing their will on you. If you want to do one, you do it. If you don’t want to do it, you don’t do it. It’s that simple,” Mirr says.

Mirr’s legal background proves its mettle in such situations. He understands the importance of precise terminology when it comes to explaining exactly what a conservation easement is and what it entails.

“There are people who think that the government is using conservation easements as a way for someone to gain access or control over your property. We have to be very careful to not imply that these easements will somehow create a public use or right,” Mirr says.

While Mirr is well versed in the legal issues pertaining to easements, he also recognizes the concerns of landowners and is able to communicate with them without getting bogged down in all the legal language.

Determining Goals

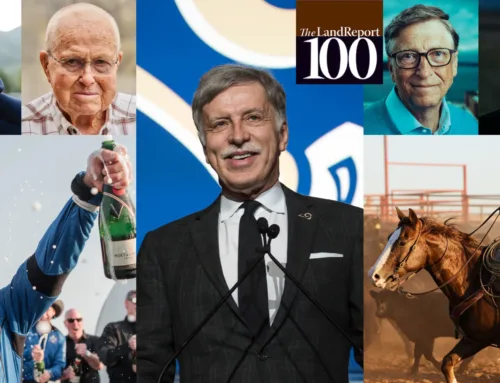

“Ken is a connector between sellers and buyers and the conservation community,” says Matt Moorhead with the Colorado chapter of The Nature Conservancy. “He has a solid understanding of the mechanics of conservation real estate and of the financial implications of those projects. So he can tell the story about not only what conservation easements are but also what they’re not. He’s good at navigating that complicated world and saying, ‘What are your goals for this land? What are you trying to do with it?’ And then he makes the appropriate introductions.” Moorhead says this ability to effectively communicate goes both ways.

CIELO VISTA RANCH. Mirr Ranch Group listed and sold this Sangre de Cristo sanctuary, which includes the highest privately owned peak in the nation.

Mirr can also explain to conservation officials the apprehension some landowners might have when it comes to the utilization of these easements. “Ken has worked hard to build meaningful relationships with people in the conservation space and has played a valuable role in the increase of the land-trust community working in the private real estate space,” Moorhead says. “He does this by being able to help translate for us what’s going through the minds of private buyers and sellers so we can then devise conservation to truly work for private landowners.”

Erik Glenn, executive director of the Colorado Cattlemen’s Agricultural Land Trust (CCALT), agrees. Mirr has been a CCALT board member for nearly 10 years, and Glenn says he has seen firsthand Mirr’s capacity for dealing comfortably with both private landowners and conservation officials.

“Ken is very knowledgeable about ranch brokerage, and he’s also passionate and dedicated to understanding and supporting conservation efforts,” Glenn says. “That gives him an advantage in the ranch world in getting landowners to look at conservation easements as a tool for their land ownership, whether it’s for conservation outcomes or financial or both.

“What Ken does very well is connect himself with credible conservation organizations that can share the message, but he also has a tremendous network of landowners he can tap into to talk with about their experience with easements. Ken will bring me and folks from our team in to talk with prospective buyers. He is diligent about making sure that his buyers understand easements.”

Colorado’s Great Divide

Of course, some might wonder why such dedication to conservation easements is needed in a state such as Colorado. After all, approximately 40 percent of the land in Colorado is public. Is further protection important when other states obviously get by with far less public land? That is where Colorado’s great divide comes into play. Moorhead points out that the vast majority of public land is confined to the western half of the state. But for true conservation benefits, he says, land protection needs to extend statewide.

“Much of our private lands began from homesteading where the water was and continues to be,” Moorhead says. “In arid Colorado, if you’re relying only on public lands, you’re going to miss some of the most significant parts of the landscape from a conservation perspective because it’s where the water is. And water is what’s going to support your native plant and animal species. “So if you’re not protecting private land, you’re missing the boat. Because the public lands need those lush, productive, well-watered areas for overall sustainability from a conservation perspective. If you want to make sure that there is a conserved resource on a large-enough scale to really work for nature and for local communities, it is critical to use tools like conservation easements in private landscapes to assemble resources that are intact and connected. That way, we can pass beautiful Colorado along to our descendants.”

The Ultimate Reward

That certainly is one of Mirr’s goals, which is why he has made conservation easements an important part of his brokerage’s scope of business. Plus, he says there are few things more enjoyable than looking out over a beautiful piece of property. That, as much as anything, is what Mirr says he loves about his job.

“The need to protect that diversity just resonates with me when I’m on these places,” Mirr says. “When I get to go on some of these ranches, I’m like, ‘I’m getting paid to do this?’ Not only to sell these ranches but to find the next buyer to be a good steward. I mean, I haven’t grown up yet. I’m waiting to grow up.”

Published in The Land Report Summer 2024.

CROSS MOUNTAIN RANCH. Mirr worked with the Boeddeker family and Colorado Cattlemen’s Agricultural Land Trust to protect 16,000 acres of sage grouse habitat.