The American Landowner: Al Biernat

The American Landowner: Al Biernat

By Trey Garrison

Photography By Gustav Schmiege III

LR_Al_Biernat-01

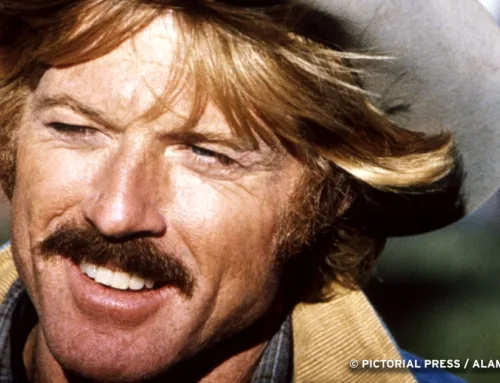

A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS. In Colorado, Biernat is equally at home carving a turn, casting a fly, or tooling around on one of his ATVs.

When it came to the Colorado hamlet of Creede, it was love at first sight for Dallas restaurateur Al Biernat. And what’s not to love about Creede? Nestled among high rocky cliffs on the eastern side of the Continental Divide, the historic mining town is the picture-perfect home of just 400 year-round residents. The rest of the year, tens of thousands of tourists and part-timers cruise through. Best of all, it’s not a ski town. Unlike Vail or Aspen, there’s no crush of obnoxious fashionistas clamoring for lattes or sashimi. Consequently, snug cabins and larger retreats range in price from ridiculously affordable to seven-figure splendor.

But Creede is no backcountry village. A tiny little Whoville of sorts, Creede boasts a slew of incredible little restaurants, art galleries, and the Creede Repertory Theatre, which has won acclaim from high-minded New York drama critics. The hunting is so rewarding that people wait years to get a permit to stalk elk, moose, and other trophy critters. The fly-fishing on the Rio Grande and its tributaries attracts anglers from around the world. And just four percent of the land in Mineral County is privately owned. The rest is controlled by the US Forest Service.

The Legendary Al Biernat

Enter Al Biernat, a self-made success who worked his way up from bussing tables at the Palm Restaurant in Los Angeles to running the Palm’s Dallas locale as its GM. When a lease came up on a prime piece of Dallas real estate, he signed on the dotted line and created the dining establishment that now bears his name. Creede was a dream come true — a place of solace, relaxation, and recreation to share with his family and friends — so he and his wife, Jeannie, bought a 30-acre plot in a delicate alpine zone at 10,600 feet. The land is regulated by the Mineral County Alpine Zoning Commission, and Biernat has a thick stack of regulations to prove it. Everything from the size of structures to the materials he could use is spelled out. Surrounded on three sides by Forest Service land, he believed his cherished investment would be protected from the over development that has plagued other Colorado towns.

Since 2005, Biernat has put a substantial amount of his hard-earned cash into his cabin and the surrounding property. “It seemed the perfect little secret place,” Biernat says. “I had no idea what could be coming.” But he should have.

Colorado’s Last Big Silver Strike

Until the mid-1980s, Creede was a mining town, site of Colorado’s last big silver strike. Since then, however, the only miners have been tourists, picking up bits of quartz and the occasional fleck of pyrite (better known as fool’s gold). Biernat was positive this peaceful oasis was immutable. He was so sure of it that he believed mining could never come back. That’s why he signed his deed, despite a standard print disclaimer and warning right above the signature line stating that he was not buying the patented mineral rights to his land. And yet, from 2007 through the end of 2008, mining returned — exploratory mining for untapped veins of nickel, silver, lead, and gold.

The prospect sent Biernat and a good number of local landowners into a tailspin of worry and doubt. They weren’t just concerned about the light and noise pollution from drilling operations or the heavy truck traffic on narrow, winding passes. Biernat was in a bind because while he owned the surface rights to his property, someone else owned the patented mineral rights. And the implications are enormous.

Different parties often own the surface and the subsurface rights. These interests may have been created through the reservation of the minerals by the government or may result from a decision by a landowner to sell their mineral interests.

Mining Claims 101

Mining claims are initially unpatented claims, which give the right only for those activities necessary to explore and mine. Much as farmers could obtain title under the Homestead Act, miners can obtain a patent (a deed from the government). The owner of a patented claim can put it to any legal use. Bottom line? If extractable ore were found beneath his property, the subsurface rights owner can force landowners such as Biernat to sell.

Mining claims are initially unpatented claims, which give the right only for those activities necessary to explore and mine. Much as farmers could obtain title under the Homestead Act, miners can obtain a patent (a deed from the government). The owner of a patented claim can put it to any legal use. Bottom line? If extractable ore were found beneath his property, the subsurface rights owner can force landowners such as Biernat to sell.

Beyond that, full-scale mining would shatter the sanctity of the Continental Divide. Biernat’s 1,000-square-foot, loft-style cabin is something out of a Ralph Lauren catalog. It’s cozy, rustic, gorgeously decorated, and at night you get a better view of the stars than the Hubble telescope. Biernat had planned to build a larger cabin and turn his existing one into a guest house. He had already added a barn-style garage for his truck, his ATVs, and the snowmobiles that are the only way to and from the cabin in winter. Needless to say, the return of mining put an end to Biernat’s construction plans. But to many longtime locals, another possibility loomed:

Was their dream of mining going to come true?

Creede Becomes a Tourist Town

After the closure of the last active mine in 1985, Creede recreated itself as a tourism hub. But tourism is a fickle trade, which even opponents of mining admit. Ed Vita, an ex-techie who moved to Creede to get away from the rat race, owns two businesses in Creede. In the winters he runs San Juan Snowcat, and he owns the popular Old Miners Inn, where you can enjoy a mean pizza and the requisite adult beverage.

We sat outside on the inn’s upstairs deck, and Vita admitted he tentatively supports the return of mining. “It’s all exploratory. Until I see the numbers and the contracts, I’m not counting on anything. I know there will be some impact on the tourist industry, but it can be hard surviving here in the winter months when it’s just the 400 locals circulating the same dollars,” Vita says.

But businessmen like Avery Auger, president of Creede America Group, love the idea of mining coming back to Creede. Creede America is developing custom homes that start in the $300,000 range. Auger is not concerned about mining. In fact, he expects to draw potential buyers from the mining operations, at least from among those in management and high-tech positions that command six-figure salaries. His development overlooks Creede and is protected by an earthen berm that blocks sight and dampens noise. “This town needs this kind of business to grow,” Auger says. “This is only going to increase property values and bring money this town needs.”

A Mining Resurgence

Brian Egolf agrees. Egolf first came to Creede with his grandfather when he was only two years old. As years passed, Egolf thought someday he would relocate to Creede permanently. After finding his way he watched the mines close. He swore one day he would reopen them.

Over the last decade, Egolf gathered patented mineral rights for large swaths of land around Creede. A savvy businessman, he knew that the depressed price of minerals wouldn’t last forever and approached Idaho-based Hecla Mining. Egolf wanted Hecla to come to Creede, test the mines, and, if profitable, oversee production.

“I’m really hoping that we can revitalize Creede, so that people can stay and earn a good living and that their children won’t leave as soon as they graduate high school, because there will be opportunities here,” Egolf says.

Hecla’s exploratory plans called for three years of exploratory mining in a 36-square-mile area, an investment of more than $12 million. But when mineral prices declined, Hecla suspended operations. Although it promises to resume exploration in the near future, many in Creede are doubtful it will return anytime soon.

That’s no relief to Biernat, who is still considering a new house, a new well, and solar power. If commodity prices rebound, mining could come back. “Do I put the money in and risk losing my investment?” Biernat asks. “I don’t know.”

Active mining operations around a recreational retreat could drive down property values long before Hecla might acquire Biernat’s cabin. Although it’s appraised at $550,000 right now, it would be worth much less if mining resumed.

When Biernat first saw his land, everything convinced him his investment would be protected. Set in an alpine zone, it is surrounded by forest service land. Brokers emphasized how mining was dead and that the town had been reinvented as a cultural and recreation hub. But unless an area is declared a wilderness, the US Forest Service allows activities on federal land like mining, timber harvesting, and grazing.

Caveat Emptor

To be fair, the fact that Biernat would not own the patented mineral rights wasn’t exactly in fine print. Biernat is a smart businessman and took a risk. And, he admits, despite all his anxieties, he doesn’t think he’d do anything different.

“I knew I was taking a little bit of a gamble,” Biernat admits. “I should have read things more closely. But I’ll be honest. If I could go back and do it again, I would, no matter what the stress and worry has been. Just the memories I built with my children and my wife make it worth it. I just wish I could be sure our investment would be safe over the long haul.”

While some of the specifics of his case are unique to Colorado law, the issue of patented mineral rights is a federal one. From coast to coast and everywhere in between, the potential for profit from subsurface minerals means that if a landowner hasn’t secured those rights, it could place their investment at risk.

Caveat emptor should be every landbuyer’s watchwords, even if they have competent lawyers and erstwhile brokers on their side. Should you find that dream spot, it just may not be possible to acquire the mineral rights to go with the surface estate. At that point, you have to measure the risk and decide if it’s worth it.

For Biernat, it most definitely has been. But it’s not something he takes lightly. Every time he talks about the issue, you can see the concern etched on his face and the troublesome pall on his otherwise optimistic visage.

“I love that town, I love the fact that it’s an artists’ community, and I love the people,” he says. “It’s taken me so long to really start to fit into the town, and I’d hate to have to leave it. But I’m blessed. I have that option. What about the guy who doesn’t have that choice?”

HEAD FOR THE HILLS. All the Biernats, Jess and Jeannie included, thrive in Mineral County, Colorado.

Published in The Land Report Summer 2009.