Red Emmerson Becomes America’s Largest Landowner

Red Emmerson Becomes America’s Largest Landowner

By Eric O'Keefe

Photography By Gustav Schmiege III

1 Opener

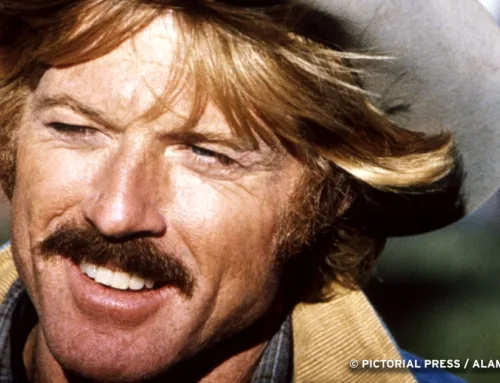

AMERICA'S LARGEST LANDOWNER. The chairman emeritus of Sierra Pacific Industries in his element outside Viola, California.

Red Emmerson grew up in a broken home. He’s the first to admit that he wasn’t a diligent student. In high school, he was sent to a strict boarding school in Eastern Washington. A few months before graduation, Red was on his own. He had been expelled. His father lived in California and his mother in the Alaska Territory. So he hired on as a hand at a ranch owned by Sam Smith, a Native American. Sam’s the one who nicknamed him Red.

The following year, he graduated from Omak High School. College was definitely not an option. At 19, all he had was a keen mind, an eye for opportunity, and a limitless capacity for hard work. Turns out that’s all he needed.

The Rise of Red Emmerson

So how did that 19-year-old end up becoming America’s largest landowner? Let’s start with the low-hanging fruit. When Red went to work at Arcata Timber Products, Harry Truman was president. Do you know anyone whose career has lasted 40 years? Sixty years? Now think about someone who has 72 years under his belt. That, in itself, is amazing, especially given that he chose the same line of work that his father had pursued with checkered success.

Curly Emmerson couldn’t buy a break. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Northwest teemed with jerry-rigged sawmills, crude contraptions in logging camps and at railheads that sputtered to life and spewed diesel fumes and sawdust. Such was Curly’s lot. Most of his mills were woefully undercapitalized. The ones that actually made money burned to the ground. Twice. Finally, in 1947, the stars aligned. He and a partner built a high-production mill that came online just as a strike shut down their competitors in California’s redwood country. They sold that mill and some timberland for almost $1 million.

As fate would have it, the buyers defaulted on the note, and the whole mess ended up in bankruptcy court.

R.H. Emmerson and Son

Then Curly made the single smartest move of his career. In 1949, he invited his son to partner with him. Red agreed, and R.H. Emmerson and Son was born: Curly would buy the timber, and Red would run the mill. The knowledge he subsequently gained of the milling industry became the second pillar of Red’s success.

There are hundreds of millions of acres of privately owned timberland in the US. Yet when lumber prices went through the roof this spring, most timberlandowners didn’t make an extra dime. Why not?

Because Home Depot doesn’t sell timber. Builders don’t buy timber. Timber grows in a forest. Builders use lumber. Yet many believe the two are one and the same. (A similar misconception applies to today’s record-high beef prices. According to The New York Times, consumers paid 20 percent more for meat this month, yet ranchers see none of those gains.)

The point is, producers rarely profit from rising prices. Processors do. Sierra Pacific Industries (SPI) not only owns 2.3 million acres of timberland, but it mills timber, sells lumber, and markets value-added products such as windows, doors, and fences. It’s those 18 mills that turn timber into profits.

The Sierra Pacific Foundation was founded by Red’s father, Curly, and is now run by his daughter, Carolyn Dietz (left). Her two brothers, George and Mark, have held leadership roles at Sierra Pacific for decades.

The Long Haul

In May 2021, lumber prices spiked to all-time highs. Few companies were poised to profit more than Sierra Pacific. Red cringes at the thought.

“I didn’t like it,” he tells me. “Not one bit. Stable markets are the best markets, and that one was out of whack.”

Wait a minute: Don’t you want to make hay while the sun shines? Not if you’re in it for the long haul. Let’s go back to the cornerstone of Red’s success: longevity.

Now let’s incorporate another factor: his profound understanding of the forest products industry. Red Emmerson may not be the best forester or the best sawyer or a retail wizard, but it’s hard to imagine anyone who can go toe to toe with him on all three counts.

The Arcata Mill

This trait can be traced back to 1949, when Curly invited Red to move to Arcata. At the time, there was a mothballed old mill along the banks of Jacoby Creek that Curly wanted to lease. Thanks to the deadbeats who had tied him up in bankruptcy court, he couldn’t get going right away. So Red took a job at Arcata Timber Products. He started on the green chain. Then he moved up to ratchet setter. After hiring on at Precision Lumber, he took on more responsibilities and got even more experience in lumber manufacturing.

By the time Curly lined up a $10,000 loan to lease the Olson Mill, Red could saw, millwright, and keep a mill going. At 20, he possessed a talent far more valuable than any college degree. As long as Curly could find timber, Red could generate cash flow. It was a total game changer. In 1950, the Emmersons didn’t own a single acre. Yet they could profit from the millions of acres around them.

Red managed to keep the Olson Mill and, subsequently, his flagship Arcata Mill, running with scavenged parts, scrap metal, and an arc welder. Back then, R.H. Emmerson and Son couldn’t afford to buy brand-new parts. Eight decades later, the family’s multibillion-dollar enterprise still shuns brand-new. Instead, it builds many of its parts at the Fabrication Shop at the Anderson Mill.

A state-of-the-art manufacturing facility, the Fab Shop employs dozens of engineers, electricians, machinists, and welders to create lumber manufacturing equipment for Sierra Pacific’s facilities. Vaughn Emmerson, one of Red’s grandsons, runs it. In his office, Vaughn shows me a schematic of a new stacker. Every one of the transfers is being built in-house. This ability — to build stackers, edgers, and other high-dollar machinery in-house — saves SPI millions.

A Partnership

The first hint of Red’s rise to industry leader came at the tail end of the Korean War. The early 1950s were good to R.H. Emmerson and Son. They had partnered with Mike Crook, a successful lumber wholesaler who also operated in the Arcata market.

Although he owned a mill, selling lumber was big business for Crook. His Pacific Fir Sales needed more inventory, which is why he fronted Curly $10,000 to lease the mothballed Olson Mill. Crook not only got his principal back, but he also took a five percent commission on every board foot that left the Olson Mill.

The deal worked so well that when Crook and a partner fell out, he brought Curly and Red on board to run his mill. The timing couldn’t have been better.

After a profitable run at the Olson Mill, the Emmersons’ lease had expired. Almost immediately, they pocketed an additional $25,000 running Crook’s mill. And after what must have seemed like an eternity, the bankruptcy proceedings that had snarled the million-dollar sale of Curly’s earlier mill finally concluded. Flush with cash, R.H. Emmerson and Son broke ground on its own mill on the Samoa Peninsula. For the next 65 years, it would be the dynamo that powered the company.

Plenty of ups and downs followed, particularly after Red was drafted into the Marines during the Korean War. While his son was stationed at Camp Pendleton and subsequently deployed to Japan, Curly bought a ranch. Soon, he began spending more time at his new ranch than running their sawmill. When Red returned in 1954, however, he quickly set out to right the ship. Just as importantly, he insisted on running a second shift. Curly balked at the idea.

“My father was perfectly happy running a single shift. ‘We’re doing fine,’ he said. But I knew we could do better,” Red says.

More than any other factor, this never-ending desire to do better, to improve, to expand, to make more, and to spend less explains Red Emmerson’s unending rise.

Bank of America

Throughout his career, Red has made one big bet after another. In hindsight, each made perfect sense. But in real time, at the moment, all of them must have seemed like climbing Everest.

The first time Red pushed his chips all in was in 1957. Georgia-Pacific had just acquired Hammond Lumber Company, and Owen Cheatham needed cash. Word got around that GP’s CEO was open to selling the timber rights to 100 million board feet along California’s Eel River.

The price was $1 million with $250,000 up front. To Red, that was “all the money in the world.”

“We just wanted a cutting contract. Not the land. It was the standing timber that we wanted to buy. I thought, ‘My God, if we ever get this paid off, we’ll have money forever,’” Red says. By then, the Emmersons had developed a relationship with their local Bank of America office, and it agreed to finance the down payment.

After paying off the $250,000 ahead of schedule, Red asked for $500,000 to buy 5,400 acres of Douglas fir known as the Davis & Brede Tract. This time he got turned down. The half-million-dollar figure exceeded the local branch’s loan limit. Red was out of answers. But Curly wasn’t. He called a friend of his from Eureka, an accountant named George Hefter. After explaining their predicament, Hefter invited father and son to meet him in San Francisco.

That trip to the City by the Bay proved to be the most fateful meeting in the history of Sierra Pacific Industries.

Meeting Frank Keene

Hefter escorted Curly and Red over to Frank Keene’s office at Bank of America’s Commodity Loan Department. As the department head, Keene could authorize far more than $500,000. Ten minutes later, the Emmersons walked out of Keene’s office with a commitment for the funds. As Humphrey Bogart’s character said at the end of Casablanca, it was the start of a beautiful friendship — for the Emmersons as well as for Bank of America.

In 1965, Weyerhaeuser decided to exit the California market. The Emmersons set their sights on two plants: one produced plywood and the other particleboard. Keene flew to Arcata from San Francisco, toured the assets, and gave them the green light on the entire $2.8 million price tag. True to form, the Emmersons not only paid off the $2.8 million note, but they did so two years ahead of schedule.

First $250,000. Then $500,000. Then $2.8 million. Was there any limit to Red’s growth plans? The $20 million he ended up borrowing from Bank of America in 1974 proved there was not.

Founding Sierra Pacific Industries

In 1969, Red and John Crook, Mike’s son, formed a publicly traded company called Sierra Pacific Industries. The two were great partners. Red knew the forest products industry, and John was a polished Phi Delt from Berkeley who could work a board room. Each complemented the other’s strengths and weaknesses. Unfortunately, Red’s focus was milling and John’s vision was a venture that no one could quite grasp: a retailer that serviced the do-it-yourself market?

Crook was ahead of his time. In 1972, seven years before Home Depot debuted, SPI opened the first of three Answerman stores. They hemorrhaged red ink. Red couldn’t stand the idea of losing money. He wanted out. But buying out Crook and the public shareholders would cost $20 million he didn’t have. Is there any doubt in your mind what happened next?

Going Private

In 1974, Bank of America financed the privatization of Sierra Pacific Industries.

Mark, Red, and George Emmerson at Sierra Pacific headquarters on the banks of the Sacramento River. Mark recently succeeded his brother as CEO. George now serves as chairman. Red continues as chairman emeritus and president emeritus.

In its first 25 years, the Emmersons acquired 33,900 acres. Four years after going private, SPI acquired 87,000 acres and two mills from Publisher’s. A decade later, the Santa Fe Southern Pacific Corporation announced it was selling its Northern California timberlands. The legacy holdings from the transcontinental railroad era totaled 522,000 acres. At the time, SPI owned 121,900 acres.

“Our company had a book value of about $120 million at that time, and Bank of America gave us a half a billion dollars’ worth of credit,” Red says.

Keene’s successor, Tony Zanze, not only extended SPI a $500 million commitment, but after the largest one-day drop in the history of the Dow Jones Industrial Average — Black Monday — the bank didn’t flinch.

Going All in on Santa Fe

Red flew to Chicago to submit SPI’s bid. He picked his price while riding the elevator to meet Santa Fe CEO Ron Krebs. When he stepped on the elevator, the figure in his mind was $425 million. When he stepped off, he had upped his bid by $40 million to $465 million.

“Oh, was it a hell of a bite,” Red says. Then again, “What would have happened if we defaulted?” he adds. “Trees would still be there.”

“It’s not like a mill that sits idle and requires maintenance,” says SPI CEO Mark Emmerson.

“Bank of America would have gotten most of its money and the funds from all the participating banks out sooner than later,” adds SPI Chairman George Emmerson. “It was a no-brainer.”

Expanding into Washington

By the turn of the century, however, the unthinkable had happened:

“We had got to the point in California where there wasn’t opportunity to expand. We owned almost 1.5 million acres, and we weren’t going to build another sawmill,” George says.

Then, a timberland manager at Rayonier named Grant Monroe contacted Red: Would SPI be interested in building a sawmill to handle Rayonier’s excess capacity in Southwest Washington?

The opportunity proved too good to pass up. To begin with, Washington was flush with timber. In the 1990s, a log export boom had stoked the market. But a spate of new regulations had changed the game. Existing mills couldn’t handle the increased capacity, and many hadn’t kept pace with advances in technology. Just as importantly, the Emmersons had all their eggs in one basket, and that basket was California, the most stringent regulatory environment in the nation.

The companies entered into a 12-year supply agreement, and the Aberdeen Mill became the first of four that SPI operates in the state. These cash-flowing mills not only added to the bottom line; they facilitated the purchase of more than 300,000 acres of timberland in Washington.

Entering the Oregon Market

In 2021, SPI entered the Oregon market, thanks in part to Red’s friendship with Aaron Jones (1921–2014). A sawmill owner, Jones purchased timberland to ensure a stable supply for his mills just as the Emmersons did. After his death, when his three daughters decided to sell, SPI was a natural fit. A deal was struck, and Seneca’s CEO and president, Todd Payne, subsequently became president and general manager of SPI’s lumber business. Although the 175,000-acre purchase was far from the biggest in SPI history, it was in fact a very big deal. For with it, Red Emmerson and his family became America’s largest landowners.

Automated Weather Stations

Although the challenges facing timberlandowners are daunting, the Emmersons are meeting them head on by proactively managing existing assets and scouting for future acquisitions.

“SPI is on the forefront of progressive fire prevention practices, and they’d be a spotlight for other companies to take a look at,” says Norm Brown, a retired deputy fire chief with CAL FIRE, California’s primary firefighting agency.

“They’ve got an incredible network of remote automated weather stations (RAWS) throughout their entire holdings,” Brown says. Working with the US Forest Service and CAL FIRE, the data from these weather stations is matched to the National Fire Danger Rating System. By integrating the two, “they are able to make comprehensive decisions about what type of activities they can do in the field.”

Although costly, RAWS safeguard the land. Other instances of sustainable forest management include thinning and reforesting after harvest. In 2020 alone, SPI planted 8.7 million seedlings. The Emmersons also invest in local communities. Red’s daughter, Carolyn Dietz, runs the Sierra Pacific Foundation. Founded by Curly in 1979, it has distributed nearly $34 million to communities and scholarship programs.

Future Acquisitions

The joke around the office is that the 92-year-old is finally slowing down. “Red doesn’t show up on Sundays as often as he used to.”

Will SPI continue to buy more land?

According to Steve Hearst, it’s in the Emmersons’ DNA to do so. He first met Red when he transitioned from Hearst’s newspaper business to overseeing its West Coast real estate holdings. As their friendship grew, he gained a better understanding of what drives this family. It’s a quest.

Says Hearst, “They’re still moving the ball towards an ever-moving end zone, if you will. They keep moving the ball down the field, and they’re doing a great job of it.”

Originally published in The Land Report Winter 2021.

Editor’s Note: Many of the historic details referenced in this article were sourced from Sierra Pacific A Family History © 1991 by J. “Bud” Tomascheski.