Salute to the Four Sixes

Salute to the Four Sixes

By Henry Chappell

Photography By Wyman Meinzer

LR_6666-Book

Go behind the scenes for a rare and revealing look at the historic Four Sixes Ranch.

Nothing reflects the culture of a ranch like its cattle roundups. The individual skill of each cowboy tells us only so much. Overreliance on flashy horsemanship, however thrilling, suggests lack of teamwork or unfamiliarity with terrain and pens.

A gathering of cattle on the Four Sixes Ranch is a deliberate, disciplined affair: A half-dozen or so riders, usually the most experienced, push 250 cows and their calves along at a trot while younger flankers gather and gradually squeeze the herd into a column. The cowboys whistle and holler and press just enough to keep the cattle moving through the open gate and into the pen. When a small problem arises amid the dust, bellowing cows, and bawling calves, cowboys converge and remedy the situation as gently and efficiently as possible. Nothing looks rushed.

A few hands dismount and gather tools, syringes, and a cooler full of vaccines. In the pen, cowboys work calmly, looking for calves to cut if they’re weaning, or to rope and drag if they’re branding. Instead of whistling and hollering, they talk to their cattle, soothing them.

During weaning, you might hear, “Yearlin’, yearlin’, shh, shh.” The veterinarians are ready when it’s time to run cows into the trap for palpitation. Other times, the unavoidable violence of dragging, branding, and castrating takes only seconds per calf. Mama and calf are reunited as quickly as possible.

Wyman Meinzer’s celebrated portrait of Anne Marion in the Croton Pasture.

The scene varies little from pasture to pasture, from one set of pens to another, over some 266,000 acres spread across three divisions. Certainly, this professionalism reflects the skill and character of Four Sixes employees. But, at a deeper level, it stems from a vision and a culture nurtured across multiple generations. Years ago, longtime Sixes cowboy Boots O’Neal described this culture succinctly:

“In a lot of outfits, you get to the pens and the boss says, ‘Okay, here’s what we’re gonna do.’ We know what we’re fixing to do before we unload the horses.”

Since its founding in the frontier era, four generations of the Burnett family have guided the Four Sixes Ranch. On February 12, 2020, after 40 years of leadership and devotion, sole owner Anne Windfohr Marion died at the age of 81. Per the terms of her will, the great ranch will not pass to another heir. The three divisions are listed for sale with Sam Middleton of Chas S. Middleton and Son for $341 million. No matter who takes title, the next owner will enjoy an unsurpassed legacy of excellence.

The Four Sixes Legacy

In 1868, 19-year-old Samuel “Burk” Burnett bought 100 longhorn cattle from Frank Crowley in Denton, Texas. The brand that would become one of the most recognized in the history of ranching — the open running six, or Four Sixes — traded with the cattle. Originally from Missouri, Burk and his parents came to Texas in 1859 after marauding Jayhawkers from the Kansas Territory torched their home. He went on his first trail drive at age 17. The following year, as trail boss, he drove 1,200 head of cattle up the Chisholm Trail to Abilene, Kansas. Already an experienced hand, he undoubtedly recognized that the Four Sixes brand would be almost impossible for a cattle rustler to modify.

In the winter of 1870, Burk bought another 1,300 head of cattle in the Rio Grande Valley and drove them up the Chisholm Trail to rangeland around the Little Wichita River. Sensing that the open range era of free grazing on public-domain lands would not continue indefinitely, he began buying property for as little as 25 cents an acre. With lumber from Fort Worth, he built his first house and headquarters at Iowa Park, just northwest of present-day Wichita Falls.

Drought, stampedes, wolves, and thievery posed constant threats. Comanche and Kiowa raiders often left the reservation near Fort Sill, and the Quahadi Comanche band still claimed the Southern Plains and vast bison herds.

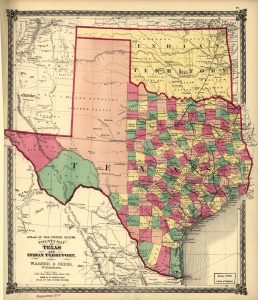

The Sixes was once part of an untamed frontier that extended from the Texas Panhandle to the Rio Grande.

Drovers pushed hundreds of thousands of cattle across the Red River and up the trail in 1871 and 1872. Reckless exuberance gave way to reality the following year when overstocked range and jittery investors sent the cattle market into a nosedive. Stuck in Kansas with 1,100 steers, the 24-year-old showed the instinct and judgement that would sustain him through rough patches the rest of his life. While other cattlemen sold at a steep loss, Burk wintered over and sold his cattle at a profit the following year.

In 1875, Comanche Chief Quanah Parker and his starving band surrendered at Fort Sill. Buffalo hunters, skinners, and wolfers who’d been hindered by the last vestiges of Comanche and Kiowa resistance stepped up the pace of their grisly calling. Cattle soon grazed in the wildest reaches of the Southern Great Plains.

Cattle prices rose in 1881 and 1882, and stocking rates soared. Predictably, prices began to drop. A punishing drought took hold in 1885, ruining weaker operations and straining the best ranches. Thousands of cattle died. Burk Burnett, Dan Waggoner, and other big operators had no choice but to look north, across the Red River, to hundreds of thousands of acres of lightly grazed Comanche and Kiowa land. Burk made a lifelong friend in Comanche Chief Quanah Parker when he leased some 300,000 acres for 6½ cents per acre.

In 1900, Congress ratified the Jerome Agreement, which opened reservation lands to settlement and forced cattlemen to vacate their leases. Every Comanche head of household was allotted a mere 160 acres for farming. Burk convinced President Theodore Roosevelt to extend his lease to allow ranchers time to sell surplus cattle and find suitable grazing.

By then, he was ready to bring his cattle home. He had purchased the 140,000-acre 8 Ranch from the Louisville Cattle Company, along with 1,500 head of cattle. In 1902, he purchased the Dixon Creek Ranch in Carson and Hutchinson counties in the Northern Panhandle, 110,000 acres of excellent summer range for fattening calves. The Burnett ranching empire grew to nearly a third of a million acres over the next few years as Burk continued purchasing adjacent lands in King County.

Around the turn of the century, Burk built the Four Sixes Supply House in Guthrie. The modest block building served as his King County headquarters as well as a bank and a commissary for his employees. Burk often slept there during visits from Fort Worth.

Less than a decade after the end of open-range grazing, barbed-wire fenced pastures, sturdy windmills, railway access, and changing tastes had rendered the iconic Texas Longhorn obsolete. Burk culled his Longhorns and replaced them with registered Shorthorns and Herefords. Within a few years, the Sixes herd was pure Hereford.

In 1917, Burk ordered construction of “the finest ranch house in West Texas.” Designed by the architectural firm of Sanguinet and Staats, the 10-bedroom mansion, constructed of stone quarried on the ranch, became the new Sixes headquarters and home of foreman J.W. Arnett. Then vice president of Quanah, Acme, and Pacific Railway, Burk traveled from Fort Worth to Paducah in a custom Pullman sleeping car with its own shower bath and electric lights. From Paducah, he would drive his buggy 28 miles south to Guthrie.

In 1921, drillers struck gas and oil on the Dixon Creek Ranch. Gulf Oil Number 1 was the first well on what would become one of the largest natural gas fields in the United States. Crude from Gulf Number 2, the first oil well in the Panhandle, flowed for 50 years.

Shortly before his death on June 27, 1922, Burk predicted the end of his cattle empire. In a letter to his friend Sid Williams, he wrote, “[Gas and oil] puts the best outfits in Texas drilling in there … of course this would put the ranch out of business as far as cattle is [sic] concerned.” In this one instance, the visionary rancher called it wrong.

Burk Burnett left his estate in trust to be inherited by the yet unborn grandchild of his only surviving son, Thomas Loyd Burnett, the oldest of his three children from his marriage to Ruth Loyd.

Like his father, Tom started early and rose quickly. Born in 1871, he worked as a line rider on both sides of the Red River. By age 21, he was wagon boss of the Burnett operation in Indian Territory. Around 1905, he leased his father’s old headquarters at Iowa Park. By 1912, he’d developed a large herd of his own, then added a fourth of the Wichita County lands owned by his maternal grandfather, Fort Worth banker Martin Loyd. Together, these holdings formed the core of his Triangle Ranch. By 1929, Tom grazed some 6,000 cattle on 130,000 acres. He and his first wife, Ollie Lake, had one daughter, Anne Valliant Burnett.

Upon his death in 1938, Tom left the Triangle to Anne, who managed it under the name Tom L. Burnett Cattle Company. “Miss Anne” lived in Fort Worth and visited the Triangle often. She and her second husband, James Goodwin Hall, were founding members of the American Quarter Horse Association. In 1978, she and her daughter Anne Windfohr Marion established the Burnett Foundation to support the arts, education, and charitable causes. She was the first woman to serve as honorary vice president of the Texas and Southwest Cattle Raisers Association and was inducted posthumously into the American Quarter Horse Hall of Fame.

Miss Anne died in 1980. Per Burk Burnett’s will, her only daughter, Anne Windfohr Marion, inherited most of the Burnett empire, including the Four Sixes. As a girl, Anne had spent summers at the Four Sixes gathering eggs, bathing in a washtub, working from horseback, developing a deep love for the ranch, and nurturing an unstinting loyalty to its people. Her art history education and studies abroad provided her with worldliness and an appreciation for high culture. Under her leadership, an already great ranch would become a world leader in range and wildlife management, Quarter Horse breeding, and cattle ranching.

Heritage of the Four Sixes Ranch

When Burk Burnett bought the 8 Ranch, his first foreman came with the deal. For 32 years, Bud Arnett ran day-to-day operations, and he led the Four Sixes Ranch from the end of open-range days into the early-modern ranching era. Upon Arnett’s retirement, longtime wagon boss Horace Bryant moved up to foreman, but left after only two years. George Humphrey, Bud Arnett’s young protégé, stepped up. From 1932 until his retirement in 1970, he led the Four Sixes Ranch through the Depression, numerous droughts, and disastrously low cattle prices. His own protégé, J.J. Gibson Jr., modernized the ranch and harmonized beloved traditional ways and newer methods. In 1998, he received the Texas Trailblazer Award, and in 2001, a few days before his death, the Foy Proctor Cowman’s Award of Honor.

In 1999, Gibson hired Joe Leathers to run North Camp, the Sixes’ 40,000-acre replacement heifer operation. Joe had grown up at Clarendon helping his father farm and run a few cattle. Ranching suited him; farming didn’t. After a year of college, he got married and began to cowboy full time. He started out running yearlings on ranches in Goodnight, Texas, then managed a small ranch in Guymon, Oklahoma. A few years later, his love of big, open country brought him to Knox County, Texas, immediately east of King County, where he worked for the Moorhouse family.

“I’ve known about the Sixes since I was old enough to know what a ranch was,” Joe says. “Nearly all young cowboys dreamed of working there. When Louise and I first got married, we’d drive by the entrance to the Dixon Creek Ranch or the headquarters here in Guthrie, and I’d think, ‘Man, I’ll never be able to work there,’ but they offered me a job, which I considered a great honor.”

After running North Camp for several years, Joe moved to town and worked as wagon boss for a short time before heading north to run the Dixon Creek Division. In 2008, Anne Marion asked Joe to come back to Guthrie and take over as general manager of the Four Sixes Ranch.

“As a young man, I never thought I’d have the opportunity to work here, but through a God chain of events, we’ve ended up running the ranch,” Joe says. “There have been a lot of changes, and Louise and I have been fortunate to be a part of those — the extreme blessing in our lives.”

And a blessing for the Sixes. During long tenures, five of the six foremen shaped the ranch in their own ways, yet all maintained a continuity of vision and a culture that lives on.

Riding for the Four Sixes Brand

Joe Leathers describes the ideal Sixes ranch horse: “Tough, smart, athletic, plenty of cow sense. Cinches up big. If I’ve got a bull on the end of a rope, I don’t want to be jerked around like a catfish on a cane pole.” As for the current quality of the Sixes remuda, he adds, “Best horses I ever rode.”

In the early years, Sixes cowboys weren’t nearly as well-mounted. After Burk Burnett’s death, all but a few of his best ranch horses were sold. When George Humphrey became foreman in 1932, he started from scratch. Burk was a businessman. Tom was a rancher first and foremost, and a better horseman than his father. Although the Sixes and the Triangle maintained separate remudas, Tom saw fit to give Humphrey a stud named Scooter, a gray out of Oklahoma racing stock. In 1940, Miss Anne donated Hollywood Gold, a yearling foaled at Iowa Park.

Over the next two decades, Humphrey’s quest to “raise a few cow ponies” established the Sixes’ breeding program as one of the best in the world. Hollywood Gold’s progeny won numerous prestigious cutting horse competitions. Grey Badger II, another Tom Burnett stallion bred to Sixes mares, produced three American Quarter Horse Association champions. Cee Bar, the only stallion the Sixes bought during Humphrey’s tenure, burnished the ranch’s reputation by producing superb competition and ranch horses.

J.J. Gibson Jr., who succeeded Humphrey, focused on breeding top ranch horses. His favorite stallion, Six Chick, produced outstanding broodmares. The 1980s and 1990s saw the great Tanquery Gin sire numerous cutting horse champions and countless gentle, highly trainable, cow-savvy ranch horses.

Four Sixes Quarter Horses

In 1982, the Sixes elevated the entire Quarter Horse industry to the next level when Anne Marion hired Dr. Glenn Blodgett DVM to convert the ranch’s breeding program from pasture breeding to artificial insemination. Schooled in animal science at Oklahoma State University and trained in veterinary medicine at Texas A&M University, he has proven himself time and again to be the right man for the very big job that his boss had set her sights on.

“Anne wanted the world’s best ranch horse production program,” Doc says. He adds, “That’s been the goal the entire time I’ve been here, and it’s our goal going forward.”

In 1993, Anne challenged Doc to increase production. “At the time, we were just raising horses for our own use and selling the excess privately, mostly in consignment auctions,” he says. “But we had the facilities and the people, so we brought back the racing Quarter Horse segment that had been a big part of our heritage with Anne’s mother, and we acquired some top brood mares as well.”

By 1993, the ranch stood top studs including Special Effect, Streakin Six, and the legendary Dash for Cash. Doc adds, “We’re unique in the industry in that we have both the Western Performance Horse segment and the racing Quarter Horse segment.”

The following year, Doc performed the first successful embryo transplants. Thanks to this key advance, young racing mares could serve as brood mares without a full-term pregnancy sidelining them from the track. The Sixes subsequently grew its stallion battery from six to 20. Typically, four or five are racing Quarter Horse studs. In keeping with the Sixes’ emphasis on top working cow horses, the remainder are Western Performance Horses.

The Sixes’ program further increased its reach in 1996 when the American Quarter Horse Association approved cool transported semen for breeding. A few years later, the transport of frozen semen was also approved. Today, Doc and his team oversee the breeding of as many as 1,500 mares annually, both on site and with shipped semen.

Return to the Remuda Sale

In 1996, Doc suggested an annual horse sale to Bob Moorhouse of the neighboring Pitchfork Ranch. “I’ve always focused on getting our name out there,” Doc says. “I knew that an annual sale would be far more effective than a sale every few years, but we didn’t have enough horses to pull it off. Bob and I decided to go in together, and then we talked to George Beggs of the Beggs Cattle Company. We started with friends and neighbors with the same vision of producing top quality Western Performance ranch horses.” The Sixes, the Pitchfork, and Beggs were joined by Tongue River Ranch and the Waggoner Ranch, and a tradition was born.

From the beginning, the Return to the Remuda Sale has attracted buyers from across the Southwest. It has grown into the premier sale in the ranch horse world. A first-class showing and performance facility was then added. In recent years, King Ranch, Circle Bar Ranch, and Wagonhound Land & Livestock have participated as guest consignors. Even with the COVID-19 restrictions, the 2020 sale proved to be the best ever in terms of both gross and average sales.

“Anne had a special way of inspiring people,” Doc says. “From the beginning, I understood that she only wanted to deal with the very best people, animals, and products. She had a way of making you feel like she was right next to you, helping you make those decisions. And to be honest, that feeling continues today. I ride for the brand.”

Sundown on the Sixes

Three Divisions

The 142,372-acre ranch at Guthrie lies along the western edge of the Rolling Plains ecological region. Both the South Wichita River and Croton Creek cut through hills, buttes, and broad draws. Given rain, little bluestem and other midgrasses grow lush in the loamier bottoms. Short grasses – curly mesquite, buffalo grass – dominate the drier uplands. King County averages 25 inches of rain per year. On a July day in 2003, in a pasture just north of headquarters, Mike Gibson turned his face up into a gentle summer drizzle, and said to me, “This might not look like much, but to King County ranchers, this is a million-dollar rain.” Thirsty country, but it makes the most of any moisture it gets.

By the 1960s, the Rolling Plains of Texas had changed from pure grassland to a scrubland of cedar and mesquite. The wildfires that periodically cleansed the prairie of brush had long been suppressed. While the advent of fenced pastures made sorting and working cattle much easier, a sea of encroaching brush turned roundups into a nightmare of spooky, brush-wise mama cows. Worse yet, deep-rooted mesquite and cedar draw down the water table and crowd out native grasses.

In the 1970s, Four Sixes Ranch foreman J.J. Gibson Jr. began an unprecedented pasture clearing program that continues today. More than 100,000 acres once choked with brush have been restored to the productive grassland that fed millions of bison and sustained the Comanche and the Kiowa. But the work never ends. Mature brush is grubbed with heavy equipment. Prescribed burning is used to quell young brush and rejuvenate little bluestem, gramma, and other native species. Violent disturbances have always played an essential role in the South Plains ecology. Given rain, the prairie heals quickly.

Today on the Guthrie ranch, bobwhite quail, Rio Grande turkey, and whitetail deer thrive as they did when buffalo hunters looked across a sea of grass. In 2014, the Four Sixes received the Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association Outstanding Rangeland Stewardship Award. Joe says, “Our decision-making process always starts with ‘What’s right for the land?’”

At headquarters, what’s right most years is a primarily Angus herd of about 4,000 cows, several hundred replacement heifers, and 200 bulls.

Dixon Creek in the Panhandle

Although the 108,000-acre Dixon Creek Division receives an average of only 22 inches of precipitation per year, calves shipped from Guthrie routinely gain 300 pounds over the summer. For the past several years, however, the ranch has served as a cow-calf operation. Dixon Creek — named after the famous frontier scout and Medal of Honor winner Billy Dixon — provides sweet water through the driest years. This is shortgrass prairie dominated by mesquite grass and buffalo grass. Massive cottonwoods shade the creeks. Plum and hackberry provide superb wildlife habitat. Joe describes the range as “stout.” Pronghorn bands graze among the cattle. Coveys of blue quail vanish into shortgrass and cholla. Mule deer watch in the distance.

Set on the High Plains Caprock, the Dixon Creek Division sits on a priceless resource the headquarters at Guthrie lacks: the Ogallala Aquifer. Six pivot sprinkler systems irrigate 2,900 acres near the southwest corner of the ranch. Currently, the pivot circles grow wheat and hay, providing a welcome safety margin against drought.

2016 Frisco Creek Addition

In 2016, Burnett Ranches purchased 9,428-acre Frisco Creek Ranch in Sherman County, north of Amarillo. Located just south of the Oklahoma line, Frisco Creek proved ideal for weaning fall calves prior to shipping. Seven pivot irrigators water 861 acres of Stockmaster Forage, a mixture of fescue, rye, and orchard grass. The remaining acreage is a mix of native and improved pasture. This small ranch can sustainably graze as many as 10,000 cattle per year. Joe says, “We’ve developed Frisco Creek into a beef factory. Now we have more diversity and a much stronger drought management plan.”

Over the decades, severe droughts have forced Sixes cowboys to graze their cattle from Guthrie clear to the Canadian border, much as Burk Burnett survived by moving cattle to Indian Territory. Yet, even with the challenges of ranching on the Southern Great Plains, Joe believes that the three Sixes divisions offer the best available balance of climate, production, and resiliency.

“If you stock this country at a reasonable rate, you’ll never run out of grass unless there’s a drought, and even then, we have alternatives,” Joe says. “There’s no place I’d rather be than right here.”

Originally published in The Land Report Texas 2021.

Update: On January 21, 2022, Taylor Sheridan was confirmed as the lead investor in the ownership group that acquired the Four Sixes Ranch from the Estate of Anne Marion.