The Battle of Bois D’Arc Creek

The Battle of Bois D’Arc Creek

By Henry Chappell

Bois01_fi

Lower Bois d’Arc Creek in Fannin County, Texas

When Harold “Thump” Witcher (right) mows a hayfield, cleans a fencerow, or feeds his cattle, he works land he may soon lose – not to a bank or to a buyer but to a certain vision of progress.

If this dam is built, 16,641 acres of hardwood bottomland, upland forest, and excellent grazing and cropland, including all of Thump’s property, will be drowned beneath the waters of Lower Bois d’Arc Creek Reservoir.

And the kicker? To satisfy federal environmental requirements, a yet undetermined acreage — likely more than 15,000 acres — will also be acquired, improved, and managed in an attempt to mitigate the loss of superb wildlife habitat that Thump and his neighbors lost.

Compact and animated, Thump describes himself as a rancher. He does have a town job, working in sales for Crop Production Services in nearby Paris. As we drive the back roads around his property, he frequently stops his pickup to point out features, elevations, and the dimensions of the proposed dam. At some stops, he grabs a big Corps of Engineers map from the backseat of his pickup and lays it on the hood for reference.

“If this thing comes to be, I will lose everything, every bit of real estate I’ve got, including my house,” he says. “My dad bought this land about 1960. And from the day he bought it, I’ve wanted to live on it.”

The Witchers moved from Grayson County to Fannin County right after the Civil War, so Thump is about as native as they come in North Texas.

In 2005, he was building his house when the reservoir issue came up. He says, “I decided that if they condemned my land, then, by God, they’d have to buy a house too.”

At last count, North Texas Municipal Water District (NTMWD) has acquired approximately 85 percent of the land needed for construction of the Lower Bois d’Arc Creek Reservoir. That includes the 14,960-acre Riverby Ranch, downstream of the proposed reservoir site, to mitigate the loss of habitat.

Holdouts like Thump, who’ve refused all offers and oppose the reservoir, could still have their farms and ranches taken via eminent domain. As a quasi-government agency, NTMWD can utilize eminent domain to acquire land for approved projects.

Reservoir supporters, especially urban business interests, believe Dallas-Fort Worth’s economic needs provide a legal and even an ethical right to rural land that belongs to others.

Like most Americans, North Texans in Dallas, Fort Worth, Arlington, and countless suburbs don’t pay anywhere near the market value of their H20. Because surface water is treated as a public resource — despite, in some cases, byzantine systems of junior and senior water rights — the citizens of Fannin County cannot claim the waters of Bois d’Arc Creek as their own. Some of the richest bottomland in the wetter parts of the Lone Star State have been inundated for the benefit of booming cities and suburbs in drier areas.

Bois d’Arc Creek rises out of North Texas’s Blackland Prairie and flows northeast some 60 miles to the Oklahoma border and its confluence with the Red River. Intermittent in its upper reaches, the creek gains volume as it snakes through the Catalpa clay of Fannin County’s post oak savannah. By the time it runs under Highway 82, just east of Bonham, Bois d’Arc is a modest but reliable stream that has graven as indelibly into the memory and culture of the region as into its pastures and woodlands

For a few miles, mostly through the southwestern reaches of the Bois d’Arc unit of Caddo National Grassland, the creek flows unnaturally straight. This is because it was channelized in the 1940s. After freshening by Coffee Mill Lake’s tailwater, the creek continues on to form the northern boundary of Fannin and Lamar Counties before nourishing the Red just northwest of Paris.

Along a few short stretches, Bois d’Arc flows clear, over firm bottom rock. Mostly it flows the color of Fannin County clay. While the creek lacks the postcard beauty of the spring-fed streams of the Texas Hill County, it’s no less rich in history or ecological wealth.

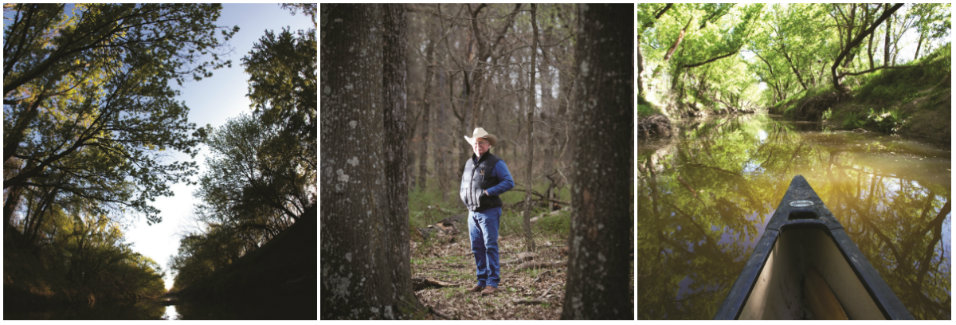

LEFT: Although Bois d’Arc Creek lacks the postcard beauty of the spring-fed streams of the Texas Hill Country, it’s no less rich in history or ecological wealth. CENTER: Thump Witcher stands among his hardwoods. LEFT: Today, Bois d’Arc Creek beckons canoeists, anglers, and hunters just as it once welcomed Native Americans and pioneering settlers.

Hunters of the Natchitoches tribe — part of the Caddo Confederacy — considered the Bois d’Arc the best beaver stream on the Red River. They called it nahaucha, “the thick,” in reference to the heavy growth of bois d’arc trees along its banks. Prior to Anglo-Texan settlement and suppression of natural, cleansing wildfire, the post oak savannah was far more savannah than oak. From a distance, the sheltering ribbon of bois d’arc and other riparian growth beckoned settlers much as it had welcomed native peoples for millennia.

While defending the Alamo, Davy Crockett may have regretted his restlessness as he fondly recalled humble Bois d’Arc Creek. On the road to martyrdom at San Antonio de Bexar, he’d stopped along “Bodark Bayou” and wrote of the richness of the country and the possibility of settling there.

Pioneer Bailey Inglish also found the Bois d’Arc agreeable. Down from Arkansas with his wife, five children, and a few other families, he settled along the creek in March of 1836. But the Caddoes were not welcoming and expressed their displeasure vigorously and frequently enough that Inglish & Co. built a log stockade.

During the Republic of Texas, Fort Inglish provided shelter and security to militia forces, including the Military Road expedition led by William Gordon Cooke in 1840. In 1843, Fort Inglish, now renamed Bois d’Arc in recognition of its sustaining creek, replaced Fort Warren as the seat of Fannin Country. In 1844, the growing town was renamed Bonham in honor of James Butler Bonham, who also died at the Alamo.

Today, Bois d’Arc Creek reflects a much-altered post oak savannah region. Although its namesake tree remains abundant, the creek flows through savannah and pasture of mixed native and domestic grasses, and sustains hardwood bottomland broad enough to be called “woodland” or “forest.”

Yet the hard-used Bois d’Arc bottomland has proven miraculously resilient. Given the slightest rest and care, it heals. Beaver, nearly eradicated by frontier trappers, are once again common along the creek, their handiwork apparent in nearly every stand of tender saplings. A stealthy canoeist can hear the slap of their broad tails, and perhaps glimpse one just before it disappears into the muddy depths.

Wildlife photographer Russell Graves, who grew up hunting the Bois d’Arc bottomlands and fishing its deep holes for catfish, has documented river otters along the creek. As black bears, a threatened species in Texas, struggle to repopulate the post oak savannah and the pineywoods, increasingly rare hardwood bottomland, like that along Bois d’Arc Creek, will be crucial to their recovery. Texas has already lost around 70 percent of its hardwood bottomland to impoundments and other land alterations.

As resilient as these bottomlands are, they will not survive inundation. The fertility — energy built up and stored over thousands of years — will be released into the reservoir to power an aquatic food chain that may, for a decade or two, provide good fishing and duck hunting before falling into decline.

Likewise, construction of a new reservoir will, for a time, unleash economic energy that may power a local economy. What form this new economy will take and how the natural wealth will be redistributed remains to be seen. At the same time, a significant portion of the current economy and tax base built on ranching, logging, farming, and rural real estate will be drowned, as will the social capital of long-established culture and memory. Whether these changes amount to a net good depends on perspective.

Egrets rest along the creek. Intact wetlands such as the Bois d’Arc Creek corridor are increasingly rare throughout the southern United States.

“Whenever you change these woods, and change this area, you change the culture forever,” Graves says. “It’s not a sophisticated culture, but my heart and soul are here. In my opinion, the culture is just as irreplaceable as the forest and creek.”

Yet water planners must plan. The population of fast-growing Dallas-Fort Worth is expected to double by 2070. Water use will increase dramatically. Elderly Dallas residents remember the 1954–56 “drought of record,” a time of unreliable tap water, when scalding water from an emergency 3,000-foot well saved the suburb of Garland from a dangerous shortage. No one charged with ensuring the state’s future water supply wants a shortage traced back to their watch.

In response to the lengthy drought, the Legislature created the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB), and voters approved a constitutional amendment authorizing issuance of $200 million in bonds to fund water development. For its first 40 years, TWDB’s water planning was a top-down affair. Agencies took a broad view of water needs and proposed solutions, primarily reservoirs. In 1950, Texas had 66 major reservoirs. By 1998, there were 203.

In 1997, after a yearlong drought, the 75th Legislature passed Senate Bill 1, which designated 16 regional groups to plan for the state’s water needs over the next 50 years. Plans are updated on a five-year basis and submitted to the board for approval and inclusion in the State Water Plan.

In theory, this approach fosters grassroots water planning. Each regional group is composed of 23 members who are supposed to represent the region’s stakeholders: agriculture, business, water development, industry, environmental, and others. The goal is to ensure that needs are met and resources are protected. Critics contend that some of the planning groups are self-electing boards dominated by representatives of water and urban business interests with little regard for rural and environmental concerns.

Consider Region C Water Planning Group, the body responsible for a 16-county area that includes Dallas, Fort Worth, and Bois d’Arc Creek. The current membership and voting privileges read like blatant cronyism to farmers and ranchers such as Thump Witcher, who may soon lose their land.

Of the 22 voting members, only one entity, Broseco Ranch in Hopkins County, represents agricultural interests. No voting representative has a direct stake in Fannin County’s agricultural economy. The representative from Texas Parks & Wildlife Department, which classifies Bois d’Arc Creek as an Ecologically Significant Stream Segment, is a non-voting member. So, too, is the representative from the Texas Department of Agriculture. The majority of the other voting members, including NTMWD executive director Tom Kula, represent municipalities, river authorities, utilities, water districts, and development interests.

Consider also the engineering analysis that forms the basis of the Region C water plan. It was performed by Freese and Nichols, the Fort Worth firm likely to receive the lion’s share of the reservoir-engineering contract. Freese and Nichols also designed, hosts, and maintains the Region C website.

Nearly wiped out by frontier trappers, the beaver (Castor canadensis) is now a common sight along Bois d’Arc Creek.

The entire length of Bois d’Arc Creek falls under the jurisdiction of the Region C Water Planning Group, which first recommended the Lower Bois d’Arc Creek Reservoir in its 2001 water plan. In 2003, a delegation of Fannin County business leaders approached NTMWD to press for construction of the reservoir. In 2005, Fannin County Commissioners Court passed a resolution supporting the project. The 2007, 2012, and 2017 State Water Plans included the project as part of a recommended strategy along with other proposed reservoirs and infrastructure projects.

According to the 2017 State Water Plan, Region C currently has available about 1.7 million acre-feet of water per year. Given population and economic growth, the plan estimates the 2070 Region C needs at 2.9 million acre-feet per year. Lower Bois d’Arc Creek Reservoir would provide some 120,000 acre-feet per year toward that shortfall. That works out to be a paltry four percent.

Some of the proposed sites, including Lower Bois d’Arc, are officially designated “unique reservoir sites.” Landowners are prohibited from modifying these locations in any way that could interfere with future reservoir construction. While typical farming activities won’t be affected, the designation could affect the market value of the land. Furthermore, landowners fearing eminent domain may be inclined to clear cut valuable timber to offset the risk of a low selling price.

In 2006, NTMWD applied for a water rights permit for Lower Bois d’Arc Creek Reservoir. Texas Commission on Environmental Quality granted the permit in June 2015. Per the Clean Water Act, NTMWD also applied for Section 404 Environmental permit from the Army Corps of Engineers, and, in 2015, submitted a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) for evaluation and comment by the Environmental Protection Agency and stakeholders. NTMWD had hoped to receive the Section 404 permit and begin construction in 2016.

A coalition formed of Texas Conservation Alliance, Natural Resources Defense Council, Audubon Texas, Ward Timber Ltd., and Ward Timber Holdings found the DEIS inadequate and recommended the Corps deny the permit. Texas Parks & Wildlife Department and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and more importantly, the EPA, agreed.

“This was one of the weakest environmental assessments I’ve seen,” says Janice Bezanson, longtime executive director of Texas Conservation Alliance. “There are lower-cost alternatives to the huge impacts of inundating over 16,000 acres, some of which is prime agricultural land and wildlife habitat. The permit requires that if there are viable alternatives, they must be evaluated. According to the DEIS, there are none. That’s preposterous.”

The Environmental Protection Agency concurred. Regarding alternative analysis, an evaluation submitted to the Corps’ Tulsa District Office on June 5, 2015, states, “[T]he Draft EIS does not study in detail a range of alternatives other than the project as proposed and the ‘no-action’ alternative.”

CLOCKWISE FROM UPPER LEFT: The red-headed woodpecker finds the rich mix of farmland and hardwood bottomland in the Bois d’Arc drainage ideal habitat. Likewise, the mallard, great blue heron, and sparrow thrive in the healthy bottomland nourished by the creek.

Chief among those possible alternatives is use of extra available water from Lake Texoma. Although the salinity of untreated Texoma water exceeds the allowable level for drinking water, possible solutions include dilution by mixing with less-saline water from other current sources and partial desalination by a membrane reverse osmosis system. The DEIS dismisses these options as impractical or unfeasible with little or no supporting analysis.

Other shortcomings include lack of assessment of numerous wetland functions, insufficient attention to the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, and an inadequate mitigation plan. The Corps agreed. A new DEIS is tentatively scheduled for release in September 2017. Stakes are high. Wrangling will continue.

Urban business interests, water developers, and politicians make a utilitarian case for eminent domain. Their accounting involves population growth, economic growth, and of course, jobs. Planners estimate that failure to add to current water capacity could cost the region 373,000 jobs and $34 billion in 2070. They assure us that while they feel for the rural landowners, we must face reality and look to the future. The landowners will be fairly compensated, or at least compensated per the terms of eminent domain. Furthermore, tourists, new residents, and businesses drawn by the new reservoir will make up for agricultural losses and the tens of thousands of acres taken from the local tax roll.

To its credit, NTMWD plans to cover the estimated $1 billion cost of the Lower Bois d’Arc Creek Reservoir from its own revenues and has pledged to compensate taxing authorities that lose revenue due to reservoir construction until reservoir-related development balances lost agricultural property tax revenue.

There can be no doubt about the profit potential of the reservoir. Lower Bois d’Arc will be the first of its kind in Texas — zoned before construction begins and perhaps even before all permits are acquired. The 82nd Texas Legislature passed Senate Bill 525, giving Fannin County zoning authority within 5,000 feet of the shoreline of the reservoir at full capacity. Fannin County Judge Creta “Spanky” Carter chairs the zoning commission.

“Overall, the local business community has been very supportive of the project,” says Spanky. “There’s a small group there that opposes the project, and I certainly understand. They’ve been out there forever, their families have been out there, and they don’t want to sell their land. But most people know that over the long haul, the reservoir will be a positive asset for Fannin County.”

More specifically, NTMWD estimates that construction of the reservoir, pump station, water treatment facility, and 35 miles of pipeline will add $509 million into the Fannin County economy, and that the completed project will increase property tax revenue by $316 million.

Texas Parks & Wildlife biologists have long fretted about the river otter, which only recently returned to Bois d’Arc Creek.

Perhaps. Yet Region C already has 24 reservoirs. All 24 compete for lake-related recreation dollars. How many boaters and anglers will forgo large, nearby reservoirs for a relatively small, shallow impoundment in Fannin County?

Consider 19,305-acre Jim Chapman Lake (formerly Cooper Lake), which can be found on the South Sulphur River in Delta and Hopkins Counties. Completed in 1991, Chapman Lake provides water storage for the same water district that includes Bois d’Arc Creek. Yet, despite the popularity of Cooper Lake State Park, the little town of Cooper just north of the lake has seen a steady decline in population since 2000. The median household income of $26,643 hardly reflects a boom. Like the water pumped out of Chapman Lake, nearly all of the wealth flows west to Dallas’s suburbs.

NTMWD hopes to receive its environmental permit in early 2018 and has vowed to start work on the reservoir the very next day. In the meantime, Thump Witcher and his neighbors are girding for the next round. “They came in here and told people that this thing is a done deal, that it can’t be stopped,” he says. “Told them that if they wait until the end, they’ll get less money. Scared a bunch of people. Not me. They hate my guts.”