Westervelt Takes Point on Chronic Wasting Disease

Westervelt Takes Point on Chronic Wasting Disease

By Cary Estes

Photography By Lance Krueger

LR_Whitetailed_Deer-LanceKrueger-01

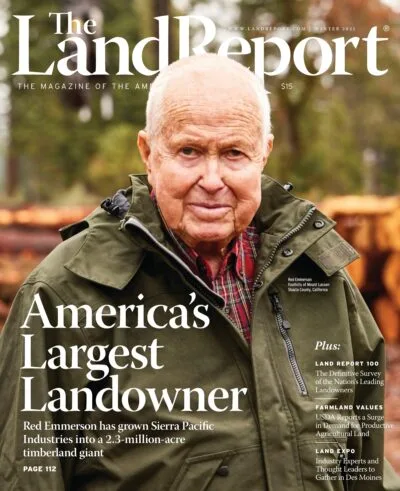

MONEYMAKER. Deer definitely qualify as cash cows.

For more than a century, timber production has been an integral part of the Alabama-based Westervelt Company. But timberland has many other uses, including environmental and recreational. It is often leased for hunting, which Westervelt has done since the 1970s. In Alabama, along with much of the Southeast where Westervelt operates, hunting primarily means whitetail deer.

Chronic Wasting Disease Detected

So when it was announced in 2018 that a case of the fatal Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) had been confirmed in a deer in neighboring Mississippi for the first time, Westervelt officials took notice. It had been 50 years since CWD was initially observed in a mule deer in Colorado, but the highly contagious neurological disease had finally made its way to the Deep South.

“If there is heavy contamination of CWD in an area, you’ll start seeing a decline in the deer herd,” says Kevin McKinstry, a wildlife biologist with Westervelt Wildlife Services. “And whitetail deer is the biggest natural resource we have. Not only would it impact our leasing business, it would affect the economy of some of these rural communities that depend on out-of-town hunters.

“So we started having some serious conversations with the leadership of this company. Our leadership has been heavily involved with wildlife restoration and management. When this threat showed up on the horizon, it didn’t take long for them to react.”

As expected, cases of CWD spread into Alabama and other southern states. In an effort to combat the disease, McKinstry helped organize a meeting at Westervelt Lodge in 2022 that consisted of seven timber companies and four conservation organizations, including the National Deer Association. The group agreed to form a CWD coalition with the goal of promoting practices to discover and manage cases of CWD and to mitigate the negative impacts.

Fighting Chronic Wasting Disease

Since there is no known cure for CWD, McKinstry said the primary objective right now is to identify any new cases of the disease as quickly as possible. This can be extremely difficult, because research has shown that the incubation period before symptoms are evident can take more than a year.

“We need to get as many samples as possible [from among the deer population] because early detection of CWD is the key,” McKinstry says. “There is no stopping CWD right now. Our goal is to slow the spread of the disease to the point that, hopefully, there might be some science that can catch up.”

Westervelt is working with its hunting-lease customers and the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources on a voluntary program where any hunter who shoots a deer on a Westervelt property has the deer tested for CWD, a process that Westervelt helps organize. McKinstry says those who agree are entered into a drawing. Each year, a hunter chosen at random receives $1,000. “We’re just trying to be proactive,” McKinstry says. “As a stakeholder, it’s in our best interest to encourage as much sampling as possible.”

Westervelt’s actions are an example of a private landowner working with officials on a problem that can affect the general public. This can be especially important in a state such as Alabama, where more than 90 percent of the land is privately held.

Published in The Land Report Winter 2024.