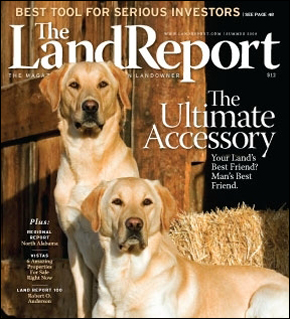

Man's Best Friend, Land's Best Friend

Man's Best Friend, Land's Best Friend

So you need a real dog. Maybe the raccoons and squirrels are fattening up on your sweet corn and tomatoes or the coyotes are dining al fresco on your lambs. Could be that after an appetizer of the latest surefire rodent killer you bought, those barn rats have cleaned out your corn crib and started to scare your cats. You need a working dog.

BY HENRY CHAPPELL

PHOTOGRAPHY BY WYMAN MEINZER

PUBLISHED SUMMER 2008

(View entire photo gallery at the end of the story)

Perhaps you could use some help loading or penning stock or rooting a few surly, rough-assed Herefords out of the brush. Or maybe you just love tough, big-hearted working dogs and would enjoy some company and a little help with the chores. First, let me encourage some self-reflection. Before you take on a real working dog, whether it’s a just-weaned pup, young started dog, or reliable journeyman, understand that working dogs are different from the fat Lab of dubious lineage, panting along on a slack lead, oblivious to the park squirrels and hybrid geese waddling around the fountain. Well-bred working dogs– dogs from bloodlines that consistently produce top performers– are born to work.

They’re hardwired for the job, whether it’s hunting, herding, ratting, guarding, or all of the above. You don’t train working dogs to work. Training merely instills a measure of control to behavior that comes naturally. If you don’t give them a job, working dogs will find their own work, usually with disastrous results. Before you begin scouting breeds and scouring web sites, ask yourself a few questions: Can you put up with chewed table legs, shredded landscaping, and bunker-sized holes in your lawn? With planning, these little disasters can be minimized, but something of he sort is bound to occur, especially during the puppy stage. Are you a perfectionist with an explosive temper?

I’m not judging you personally, but if that’s your temperament, you probably shouldn’t work with dogs, even if they’re professionally trained. Are you willing to put in 15 to 30 minutes of training on most days, especially during your dog’s first year? Do you really have work for the dog? If not, then consider getting a nice, easygoing rescue dog instead. Hayrides don’t require a thoroughbred.

Most important, do you truly love dogs? I don’t mean like dogs, as in you’ll pet a nice one if it comes up to you and starts wagging its tail. I mean are you drawn to them? Do you think about them often? When you visit friends, do you spend as much time fooling with their dogs as visiting?

Some of the breeds I’m about to recommend are virtually unknown among casual dog owners. My selections are based on firsthand experience or recommendations from hunters, stockmen, and trainers whose opinions I respect. Ultimately, it comes down to individual dog and handler, not breed, but certain breeds and bloodlines are far better bets than others.

FEISTS

Working dogs needn’t be large. In fact, for dispatching small vermin, guarding the pea patch, watch duty, and general companionship, small working dogs may be your best choice, especially if you have to trudge back home to the city or the suburbs to earn the payments on your country place. Most native Southerners, especially those with rural roots, will call any small dog that trees squirrels a “feist,” “fice,” or “fice dog.” Nowadays, breeders are developing feists of more uniform appearance and performance, but all the old working traits are still intact. A few minutes spent watching a good feist work will give new meaning to the word “feisty.”

Feists are terrier-like in appearance and temperament and working-class in origin. Their lineage goes back to terrier breeds developed in Great Britain for the purpose of hunting small vermin, especially rats. Immigrants brought their terriers with them to North America and bred the little all-purpose dogs for increased hunting and scenting ability by crossing them with curs, beagles, and other trailing hounds. Gradually, the various local and regional feist strains emerged and are still developing as breeding programs stress certain working qualities.

Feists are companionable, eager to please, and make first-class vermin dogs, watchdogs, and small-game hunters. Some will even take on light stock-herding duty. Consistent with their terrier background, feists are fearless and incredibly alert. Their attitude and purpose can be summed up by this stance on treeing feist conformation in the United Kennel Club breed standard: Scars should not be penalized.

RAT TERRIERS

Not surprisingly, a rat terrier catches and kills rats. And like feists, rat terriers will do just about anything else that needs doing. My old friend Donny Lynch, a trapper and hunter and one of the best outdoorsmen I’ve ever known, swears by the breed. His current rat terriers, Chance and Rafe, tree squirrels and coons, work feral swine, and keep his camp and vegetable garden safe from marauding critters and vermin of the two-legged variety. They also sleep under his bed and entertain his grandkids. A word of warning: Be sure to select puppies only from proven working bloodlines. Rat terriers out of pet and show stock are all too common.

PUREBRED CURS

“Registered cur” is not an oxymoron, although overly fastidious elements in Dog Fancy might take exception. In general, curs are all-purpose hunting and stock dogs of long and varied lineage. Although the cur’s exact ancestry is impossible to pin down, we know that its origin traces back to yeoman stock and hunting dogs from Europe. The origin of the name “cur” is open to speculation. Some suggest that the word derives from “courtail” or “curtail,” which describes peasant working dogs with tails bobbed to distinguish them from the hunting hounds of the aristocracy. More likely, the dogs’ tails were bobbed because English dog taxes were based on the length of the dog from head to tail. Medieval peasants were poor, but they weren’t stupid.

Of the numerous cur breeds and types, two stand out in terms of consistent performance and availability of excellent pups: the blackmouth cur and the mountain cur. Although the blackmouth cur is most associated with the Big Thicket of East Texas, the breed’s versatility makes it popular with stockmen, hunters, and search and rescue teams all over the country. Tough, intelligent, and usually personable, the blackmouth will tree raccoons, squirrels, and other climbing game and handle the wildest cattle and swine.

Enthusiasts say the mountain cur made settlement of the Southern Appalachians possible. Slightly smaller and typically more tree-oriented than the blackmouth, the mountain cur herded stock and treed small and large game, including bears and cougars, and guarded frontier homes and property. The mountain cur is a serious varmint dog and an excellent choice for hunters with modest stock-working needs. If your property is in bear country, rest assured that a couple of mountain curs will send a bruin packing.

RETRIEVERS

I’m afraid I’m about to offend some readers. In North America, “retriever” almost always means Labrador, golden, or Chesapeake Bay. I’m a big believer in the big two, not the big three.

Although I’m a fan of the breed and can heartily recommend the golden retriever as a family pet, I’m afraid I can’t recommend it as a rough, allpurpose ranch or farmdog.While working-stock goldens make fine hunting dogs, their soft temperament–a trait that suburban families love–makes them poorly suited for general-purpose country work.

No doubt there are exceptions, just as there are a few goldens that can compete with Labs in field trial competition, but they are rare. Nowadays, because of overbreeding for large size and an excessively long, silky, useless coat, finding a golden that’s free of skin, eye, hip, dental, and elbow problems can be a challenge. And that’s a shame. Let’s hope dedicated breeders more interested in working traits than showring fashion can bring back the tough, versatile water dog once popular with British gamekeepers. That leaves us with the two workhorses of the retriever world: the Labrador retriever and the Chesapeake Bay retriever.

The Labrador has dominated retriever field trials for the past century. A good Lab is perfect for the landowner who needs an easily trained generalist around to woof at strangers, play with the kids, guard the henhouse and garden, and fetch waterfowl and upland game birds during hunting season.

My friend James Collier, a veteran pro trainer and hunting guide, offers five reasons for owning a Lab: drive, personality, versatility, trainability, and consistency. “The thing about Labs, especially the ones they’re breeding these days, is that they come with such high hunting and retrieving drive,” he says. “They have all the attributes you need in a good gun dog, plus they have the disposition that makes for an ideal family companion.”

| SHOW US YOUR DOG |

| Send photos of your best friend to [email protected]. We’ll take the top shots and put them on the site and send the winners a free subscription to The Land Report. |

Unlike the Lab, which was developed in Newfoundland and refined on the British Isles by genteel sportsmen, the workaday Chesapeake Bay retriever retains many of the qualities of the 19th-century market hunters he served so long andwell. A truly American breed, developed to retrieve hundreds of ducks a day fromrough, coldwater, the Chessie is independent, protective, and learns best on the job. The old market hunters had little time for formal training. With his harsh outer coat and wooly undercoat (both oily for water repellence), the Chessie can break ice all day and holds up surprisingly well in hot weather.

There is no tougher dog in the world. Like the Lab, the Chessie should make a fine all-around farm dog and companion as well as a first-rate duck fetcher. Although Chessies are territorial and might keep the extension agent in the truck until you step out the front door, they’re rarely aggressive enough to get you sued. They tend to be especially protective of children.

HERDING DOGS

If you raise sheep and enjoy flashy, exacting stock dog work, you can’t go wrong with a border collie. Often touted as the world’s most intelligent breed, the border collie is without a doubt the most highly refined of the herding dogs. While good ones abound, mediocre and sorry ones are all too common, thanks to the influence of the show ring. Choose with care, and you’re likely to be rewarded with beautiful, lovable, relentless workers.

If you run a cow-calf operation, you’ll need a dog with more grit than the average border collie. And you won’t find a grittier breed than the Catahoula leopard dog, also known as the Catahoula cur or Louisiana Catahoula. Nineteenth-century cracker cowboys prized leopard dogs for their ability to root wild cattle out of the dense Florida palmetto flats. Given its background, it’s not surprising that the Catahoula is a bit rough for some kinds of work.

They’ll eat your sheep up getting them into the pen. But a good Catahoula will make a reasonable animal out of the surliest mama cow. Randy Walker, of Ranger Creek Ranch in North Texas, has worked with cow dogs for the past 30 years. He loves border collies and Catahoulas.

Naturally, he crosses the two breeds to get the trainability of the border collie and the grittiness of the Catahoula. “I’ve tried Australian shepherds,heelers, and most of the other common breeds, but I’ve had the best luck with Catahoulas and border collies. And these crossbreeds are working great,” he says.

His advice for prospective cow dog owners? “Papers don’t work. Dogs work. Make sure you’re dealing with reputable breeders who guarantee their pups,” he says. “If a breeder isn’t willing to replace a pup or refund your money if you aren’t satisfied, then look elsewhere.”

That’s good advice, regardless of breed.

———————————-

Wyman Meinzer and Henry Chappell are collaborating on Working Dogs of Texas, scheduled for publication by Collectors Covey in the autumn of 2009.